A recent New York Times story on the ordinary Nazis among us ignited a minor firestorm of controversy, not least in presenting the Nazi next door as a surprising phenomenon.

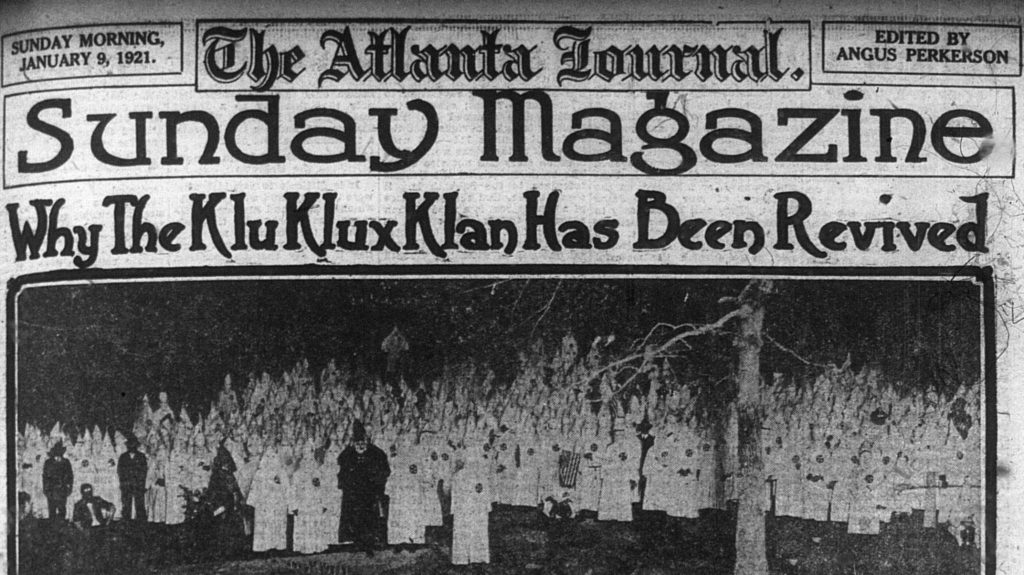

The article has been rightly criticized for not placing its subject in the broader socio-cultural context and allowing the interviewee to “drive the narrative of his own white supremacy.”1 But there are also serious problems in divorcing the subject from the long history of “respectable” and “normal” white supremacists in the United States – including the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s.From its “rebirth” with a cross burning at Stone Mountain in 1915, the self-proclaimed “Invisible Empire” was intimately intertwined with daily life in Atlanta. As the standard narrative goes, this second Klan initially met with limited success. It was not until 1920, when Imperial Wizard William Joseph Simmons forged a partnership with Edward Young Clarke and Elizabeth Tyler of Atlanta’s Southern Publicity Association, which had previously run “booster campaigns” for the Anti-Saloon League, the Salvation Army, and the Armenian Relief Fund, among others. It was under Clarke and Tyler’s direction that membership finally began to soar. Paid recruiters sold the Klan not only as a white supremacist organization, but as a staunch supporter of law and order, an enforcer of public morality, a guardian against Catholic and Jewish immigration, and the purveyor of a white Protestant American fraternalism. Aided by the publicity provided by national newspaper coverage, the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s transcended its sectional origins to garner truly national popularity. While estimates vary, historians have generally concluded that Klan membership peaked in late 1924 at somewhere around four million members throughout the United States.2

Where this narrative remains insufficient, however, is in its overemphasis on paying membership numbers to determine the waxing and waning strength of the Klan. In my new book, Ku Klux Kulture: America and the Klan in the 1920s, I argue that a core-periphery model that prioritizes affiliation ultimately limits our understanding of the broader power that the Invisible Empire wielded in that historical moment. We must understand the Klan not simply as a social organization, but also as a cultural movement. An imagined cultural community of Klannishness extended far beyond the organization’s paying membership, and was disseminated in popular music, film, literature, and more. The men and women of the Klan were more than capable of both enjoying contemporary mass culture and turning it to their own ends. And at the same time, popular commercial entertainments co-opted the image of the Klan, sanitizing and normalizing the Invisible Empire for a mass audience. This was no fringe element – these were the Klansmen next door. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the Klan’s “Imperial City” of Atlanta.

While Indianapolis and Denver may arguably have boasted a larger membership (though estimates of Klan strength in Atlanta run to a not inconsiderable fifteen thousand members), the Imperial leadership of the Klan in the early 1920s was deeply embedded in everyday life in Atlanta. Clarke and Tyler, the Klan’s recruitment heads, formed their own realty company to manage all the Klan properties in the city, from the Imperial Palace on Peachtree Road to Elizabeth Tyler’s fourteen acres on Howell Mill Road to the short-lived Lanier University in Morningside. This substantial physical presence in the heart of Atlanta reflected the Klan’s influence in the city.

In politics, for example, Fulton County Solicitor General John M. Boykin and Fulton Superior Court Judge Gus H. Howard were both Klansmen. The Klan’s chief lawyer, Paul S. Etheridge, himself sat on the Fulton County Board of Commissioners of Roads and Revenues. Klansman Walter A. Sims was elected mayor of Atlanta in 1922, in a campaign centered on the prohibition of interracial worship. And after being tagged as insufficiently supportive of Klan efforts, in 1922 Georgia’s Governor Thomas Hardwick was voted out of office and replaced with ardent Klan supporter Clifford Walker.It is in cultural pursuits, though, that we see the full extent to which the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s had been absorbed into the ordinary, everyday white supremacism of life in Atlanta. Whether a member or not, you could stop at newsstands across the city to pick up a copy of the Klan’s newspaper, Searchlight. Financed by Tyler and edited by J. O. Wood (who was also a member of the state legislature), the weekly focused its reporting on the ostensible good deeds and charitable works of the Klan, mixed with local news and comment. More than sixty thousand people purportedly read Searchlight each week, and the publication carried advertisements from a wide cross-section of local businesses, including Coca-Cola.

Within the pages of Searchlight, we find the vibrant cultural life of the ordinary white supremacist. For those seeking an evening’s entertainment, the citizens of Atlanta could attend a Klan-organized screening of the smash hit Birth of a Nation or one of the increasing number of the Klan’s own feature films. They could turn on the radio to listen to Klansman Fiddlin’ John Carson, or purchase one of the OKeh recordings of his music – recordings which helped create country music as a commercial genre.3 Maybe they would be lucky enough to catch the traveling stage show, The Awakening, which mingled the plot of Birth of a Nation with musical numbers and cabaret-style showgirls. Since the show relied on local amateur theater to fill its ranks as it moved from town to town, many Atlantans also appeared in the production.

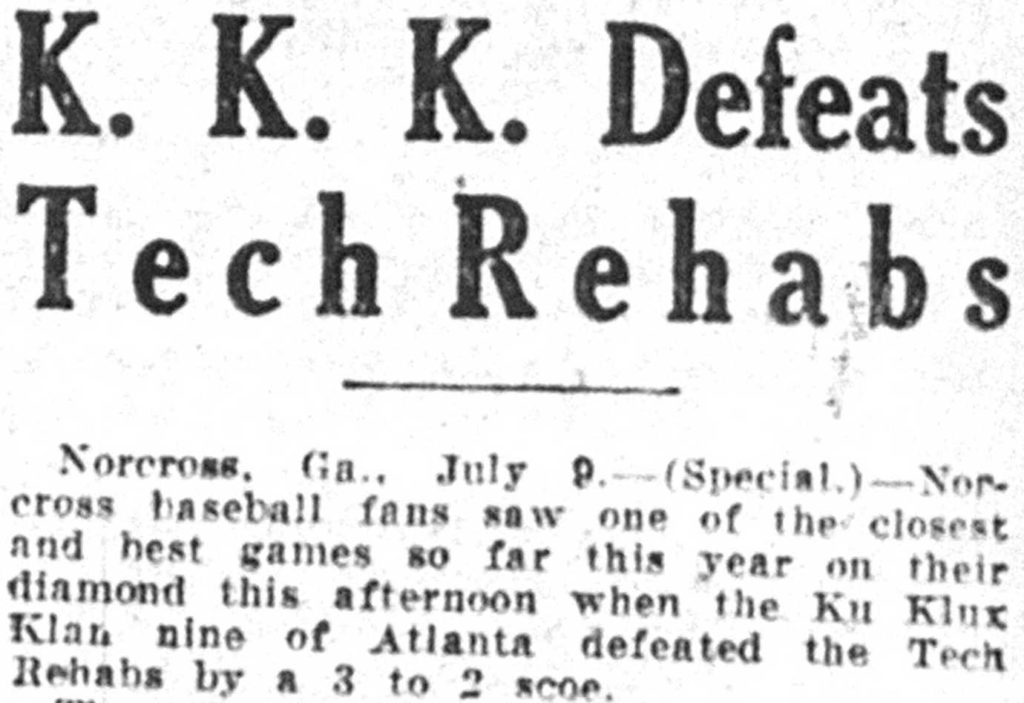

If readers turned instead to the sports pages of the Atlanta Constitution (where Edward Young Clarke’s brother worked as managing editor), they could find box scores for the Atlanta Klan’s baseball team. In 1924, the Klan played in the amateur Dixie League against teams including their neighbors from the Peachtree Road Presbyterian Church, Georgia West Point, and the Georgia Railroad and Power Company. In a reflection of the Klan’s immersion in everyday life, the rivalry between the Klan team and the Georgia Tech Rehabs team for the league pennant (eventually won by the Klan) garnered far more press attention than the Klan’s nonleague games against more surprising opponents, including the Catholic Knights of Columbus.4 Clearly, membership in the Invisible Empire was no bar to participation in community life.

This is not to say the Klan was without controversy. Atlanta was also where the Klan’s dirty laundry was aired – where Clarke and Tyler were arrested on morals charges; where the Klan’s leading religious official, known as the “Kludd,” Caleb Ridley was arrested for drunk driving; and where the Klan’s press chief, Philip Fox, shot his rival, William S. Coburn.5 And gradually the Klan’s presence in the city lessened. As Hiram Evans wrested control of the Klan from Imperial Wizard Simmons and focused increasingly on politics, he would make Washington, DC, the new Klan headquarters. Ultimately, the Klan’s Imperial Palace would be sold off to an insurance company, who then sold the property to the Catholic Church. It is now the site of the Cathedral of Christ the King.Yet the Klan’s legacy lingers on in Atlanta. While seemingly emboldened in recent months, and the subject of rising visibility, contemporary white supremacists did not appear from nowhere.

The Association of Georgia Klans, headed by Atlanta obstetrician Samuel Green, was established with another cross burning at Stone Mountain in 1945. As Green’s organization faded, it was supplanted by the U.S. Klans in the 1950s. Even as the city became an epicenter for the Civil Rights Movement, a summit just south of Atlanta saw the creation of the United Klans of America. At a 1962 Fourth of July protest at Stone Mountain, robed Klansmen mingled with other segregationists and neo-fascists from the area. Over the past decades, the Atlanta metro region has continued to provide a home for branches of the Loyal White Knights of the Klan, the Aryan Nations, and the many others who may pay no formal dues but nonetheless share white supremacist views. Just as with the men and women of the Klan in the 1920s, these men and women today are not strange, otherworldly creatures, incapable of ordinary human interests, but rather all too familiar. Examining the Klan’s past cultural endeavors reminds us of the insidious and pervasive presence white supremacism has held in everyday life. Such examinations are critical. Until we understand the deep-rooted history of that presence, we will remain unable to truly reckon with the “normal” white supremacists of today.

Citation: Harcourt, Felix. “White Supremacists Within: The Ku Klux Klan in 1920s Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. December 12, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20171212.

Notes

- @mangi_jay, “4/ Otherwise you are just giving a racist an unchallenged platform,” Twitter, November 26, 2017, 3:07 p.m., https://twitter.com/magi_jay/status/934876167257165825.[↩]

- Thomas Pegram, One Hundred Percent American: The Rebirth and Decline of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s (Maryland: Ivan R. Dee, 2011), 10, 16, 20.[↩]

- For more on Carson and country music in 1920s Atlanta, see: Steve Goodson, “‘The Nashville of its Day’: Recalling the Origins of Recorded Country Music in 1920s Atlanta,” Atlanta Studies, August 9, 2017, https://atlantastudies.org/2017/08/09/steve-goodson-the-nashville-of-its-day-recalling-the-origins-of-recorded-country-music-in-1920s-atlanta/.[↩]

- “K.K.K. Defeats Tech Rehabs,” Atlanta Constitution, July 10, 1924, 10; “Klan Defeats Tech Rehabs,” Atlanta Constitution, July 31, 1924, 15.[↩]

- Clarke and Mrs. Tyler Arrested While in House of Ill Repute,” New York World, September 19, 1921, 1, 4; “Reckless Driving and Drunkenness Laid to Ridley,” Atlanta Constitution, October 18, 1921, 1, 7; “W. S. Coburn, Attorney for Simmons Faction, Killed By Editor of Official Organ of Klan,” Atlanta Constitution, November 6, 1923, 1.[↩]