Citation: Rasool, Adnan. “Mapping Atlanta’s Rap Footprint.” Atlanta Studies. February 13, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20180213

Working off the notion that art is informed by its surroundings, the Rap Map project in ATLMaps explores how Metro Atlanta has impacted not just the artists that call the city home but a whole genre of music by spatializing that impact.

As members of the Student Innovation Fellowship (SIF) program at Center of Excellence in Teaching and Learning (CETL) at Georgia State University, Brennan Collins and I set out to explore the spatial dimensions of the work of some of the most influential hip hop artists in the last two decades hailing from Atlanta. We took up the works of OutKast, Ludacris, and Childish Gambino – three Atlanta artists that have shaped hip hop at different times in recent decades. We analyzed their lyrics to find every reference to Atlanta and then mapped that out in our pursuit of new patterns. While Brennan focused on OutKast’s work, I explored Childish Gambino. We worked together on Ludacris’s map layer to ensure nothing was missed.]Our map highlights that the rapid pace of development in the city has had a negligible impact on how hip hop music engages with the city’s geography. Our purpose in this project was to show the significance of music as a source for an aural history of cities and towns as well as to explore the symbiotic relationship of art and space.

We started with a simple idea: to map out the lyrical references to Atlanta and its locales found in the works of three acclaimed rap and hip hop artists of different periods over the last twenty-five years – Childish Gambino, Ludacris and OutKast. We began with OutKast, as they are often credited as the founders of what has come to be known as the ‘Atlanta Sound.’ At a time when the city was going through gentrification intown after the 1996 Olympics, OutKast’s music spoke to a new generation of Americans who could relate to the oncoming gentrification phenomenon that was revitalizing decrepit areas in major cities.1 In such a scenario, the physical space became a sign of belonging and gaining legitimacy for the new artists who wished to signify their street credentials/authenticity.2

This unique style of calling out the areas they originated from influenced prominent later musicians like TI, Lil Jon, Usher, Migos, Young Jeezy, and 2 Chainz.OutKast’s first album in 1994, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, was critical in establishing Atlanta as a serious site for hip hop in a field that had been dominated till then by New York and Los Angeles. Outkast broke through the East Coast-West Coast rivalries and gave hip hop a new voice – a uniquely southern one. OutKast even proclaimed in their acceptance speech at the 1995 Source Awards that the “South got something to say,” asserting that a new, uniquely southern, sound had been born.

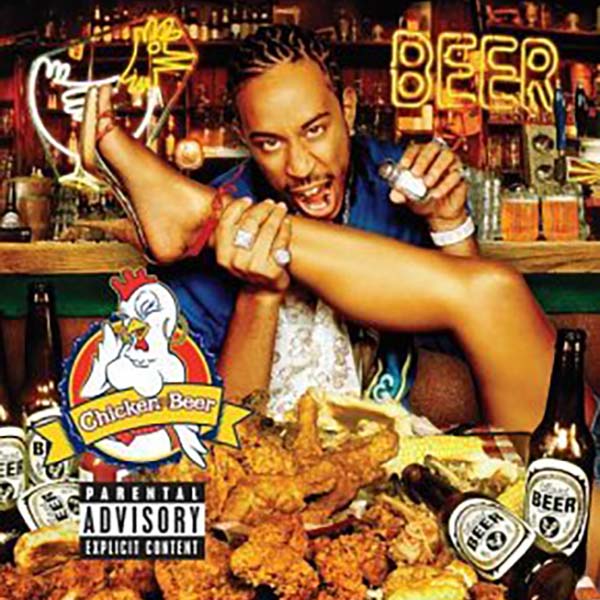

Nine years later, Ludacris’ 2003 album, Chicken-n-Beer, cemented Atlanta’s position in the hip hop world, smashing album sale records in the process. The secret track on that album, Welcome to Atlanta, is effectively a drive through Atlanta from the perspective of a hip hop artist who has finally made it big but remembers his roots. While Ludacris rode in on the waves made by OutKast’s struggle to be heard and achieved unprecedented popularity, more recently Childish Gambino’s music has offered a more nuanced approach to the city that tackles everyday reality. Childish Gambino’s debut 2011 album Camp represents an evolved Atlanta sound that takes up the hard realities of living in an ever-changing city and fighting odds that are constantly stacked up against you.3

As we set out to map out these lyrics and create a spatial map, we encountered difficult choices. The biggest challenge concerned the many locations and businesses mentioned in lyrics which were now either shut down or had moved. In such cases, we faced the dilemma of whether we tag the new location or the original one. Should we skip out on businesses or locations that do not exist anymore? Another issue that arose as the project progressed was how to manage instances where the same location was repeatedly referenced. Similarly, we confronted a conundrum over where to put down markers for more generic places/regions like College Park or Atlanta itself. Finally, we were forced to ask whether the references to places in the songs necessarily meant what we thought they meant. For instance, there is a skating rink called GLIDE in Decatur, but when a song mentions that word is it specifically referring to the skating rink, or is it just using “glide” as a more generic verb?

Addressing each of these choices and dilemmas properly was critical and we’d like to explain our decisions. First, we dealt with the issue of the same place being referenced multiple times by slightly spreading out markers around it. This allows us to cluster all the references, highlighting that the place is mentioned repeatedly, yet without making the layer visually over-cluttered and difficult to navigate. For example, Greenbriar Mall and Banaker High School in South Atlanta are referenced multiple times by Ludacris. And all three artists talk about Lenox Square Mall as a somewhere the elite of Atlanta go. We spread the markers on opposite ends of the property so all references mark various parts of the same location. For more generic references like Atlanta, College Park, or Decatur we chose pinpoints close to a main area, to the best of our knowledge. Then we spread all the references close to each other but with a street or two in the middle as distance, again to avoid creating a visually over-cluttered and difficult to navigate map.

For instance, we chose a central downtown area close to the Garnett MARTA Station that cuts across Peachtree Street, Poplar Street, and Broad Street to mark anything that references the generic Atlanta and located the various references at different points on the immediately surrounding streets. Finally, for closed businesses or names that sound like a business, we discussed the lyrical references with people who have lived in Atlanta for a long time. Their knowledge helped us highlight cultural landmarks and identify important contexts for interpreting the music. Dealing with these dilemmas ultimately taught us a lot more about the city, the evolution it has undergone, and the places that still exist in music and archives, but that have vanished from the contemporary cityscape.

The current Rap Map highlights a few interesting trends. First and foremost, across the work of these three artists, lyrical references cluster near the same neighborhoods, places like East Point, Decatur, Stone Mountain, and College Park. These neighborhoods have seemingly remained relevant for musicians throughout the last twenty-five years. Moreover, starting from Stone Mountain in the East and ending at Bankhead in the West, hip hop’s Atlanta looks for the most part like a distinctively south of Midtown affair. This spatial mapping suggests that music too demarcates the city’s well-documented economic, political, and racial North–South divide. The history of hip hop in Atlanta is exclusively a South Atlanta affair.As the city gentrifies southward beyond the Five Points North-South divide, through these maps we can also find evidence of those cultural hotspots that have been lost. For instance, in Childish Gambino’s “Dream/Southern Hospitality/Partna Dem,” he mentions bringing back SciTrek and Turner Field. SciTrek was a sci-fi aficionado spot in Downtown Atlanta and Turner Field, until recently the home of the Atlanta Braves, is now the Georgia State football stadium.

Both locations are in downtown Atlanta neighborhoods in the midst of gentrification. Mapping these musical references places hip hop songs in the historical context of the city’s gentrification. Childish Gambino’s longing for closed venues in neighborhoods also called out by OutKast illustrates how these changes are reshaping the landscape that informed the ‘Atlanta Sound’. And this is exactly the point of this project; to map out the aural history of Atlanta as captured in the music produced here. This project is a spatial anatomy of Atlanta’s influence on hip hop as we know it.