The Atlanta City Council is currently considering whether to designate the building at 152 Nassau Street as a historic landmark.

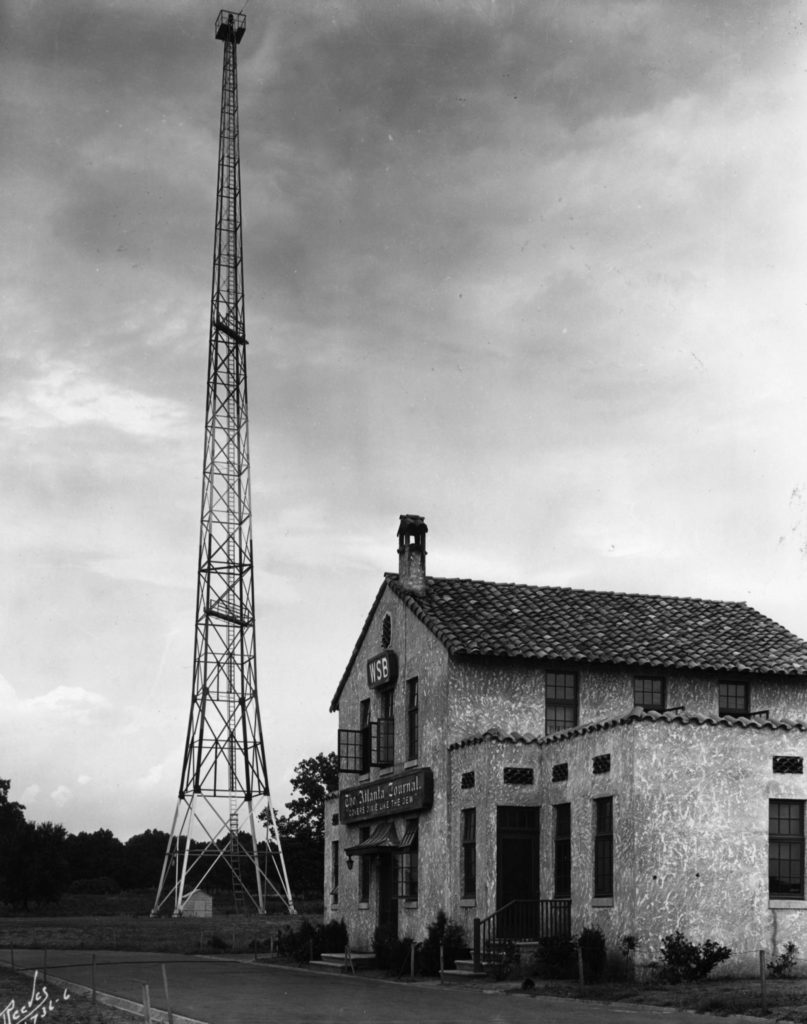

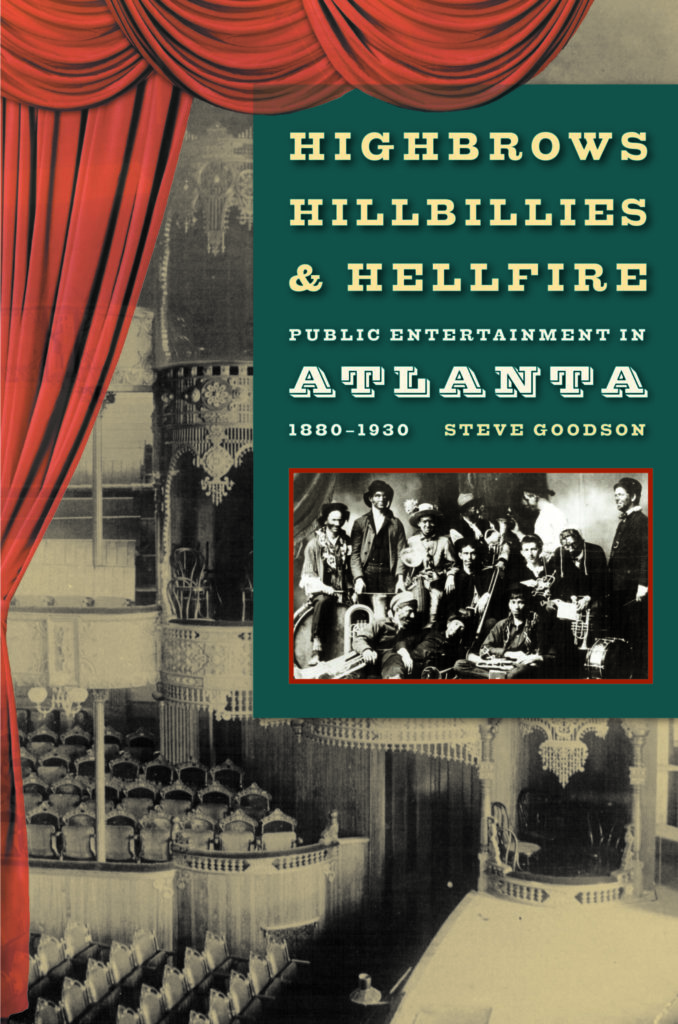

This is as a buyer of the property hopes to demolish the structure and build a Margaritaville. As first reported locally in the June 2 Creative Loafing article “The Little Old Brick Building on Nassau Street” and the July 24 WABE radio piece “First Country Music Radio Hit Traced Back to Atlanta Building,” and more recently publicized by the widely republished August 8 Associated Press article, “Atlanta Building Steeped in Music History Faces Demolition,”1 the attention to this building has brought to light a little-remembered but significant chapter of Atlanta’s history. Long before Nashville began billing itself as “Music City,” Atlanta served briefly as the country music and blues recording center of the United States. As I observed in my 2002 book Highbrows, Hillbillies, and Hellfire: Public Entertainment in Atlanta, 1880–1930, from which this post is adapted, this story has deep historical roots and resulted from the convergence of a number of cultural, demographic, economic, and technological trends.2 But as good a place as any to start the tale is March 15, 1922, with the debut of radio station WSB, which promoted itself as “The Voice of the South.”WSB was the South’s first radio station and enjoyed a tremendous broadcasting range. As early as 1923, the station’s estimated nightly audience exceeded two million, and WSB’s advance programs were being mailed to newspapers in more than thirty states.

To fill its airtime the young station required a never-ending flow of entertainers, and a strikingly varied group answered the call. It was not at all unusual on WSB for a “hillbilly” string band to go on the air sandwiched between a classical pianist and a jazz saxophonist.3 Remarkably, WSB even extended its welcome across the color line, giving African American musicians unheard-of access to a national audience.

Not everyone welcomed the advent of radio broadcasting that WSB heralded. The record companies saw radio as a serious commercial threat and responded by seeking out new audiences for their wares and new performers who might appeal to those audiences. In particular, some in the business felt that African Americans and southern whites represented two potentially lucrative markets, and so engineers set out, portable recorders in hand, to test the waters. Atlanta quickly became a principal destination. A major beneficiary of the long-term exodus of blacks and whites away from the countryside, Atlanta harbored a wealth of musical talent, and the presence of WSB already attracted many additional musicians to the area. At the same time, Atlanta appealed to the record-industry men because as a rail center it was easily accessible and offered a “big-city” atmosphere to technicians and talent scouts accustomed to the amenities of New York.4

“Pluperfect Awful”

On June 19, 1923, the commercial history of country music began as Fiddlin’ John Carson, hero of many a local fiddlers’ convention, entered a vacant building on Nassau Street to record “Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane,” an old song lamenting the passing of rural life, for the New York-based Okeh Record Company. Whether referring to Carson’s performance or to technical aspects of the recording, Okeh executive Ralph Peer famously deemed the result “pluperfect awful,” but he had to reconsider when the original five hundred copies sold out quickly in Atlanta, necessitating a repressing.5 Carson was not the first artist to record country music – Texan Eck Robertson and Virginian Henry Whitter had narrowly preceded him – but Fiddlin’ John somehow caught on where they had not, and an industry rose in his wake.

Carson was a pivotal figure in the cultural history of Atlanta and the South not only because of what he did, but also because of what he represented. Born just after the Civil War in North Georgia’s Fannin County, Carson labored variously as a farmer, railroad hand, moonshiner, mill worker, and house painter. He brought his family to the Atlanta area in 1900 to work for the Exposition Cotton Mill, and in 1911 they moved into a four-room company house in Cabbagetown, a community adjoining the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mill where John and other family members signed on to toil twelve hours a day. Then, during a 1913 mill strike, Carson earned change as a street musician, “busking” for coins on Decatur Street and in other likely locations. Indeed, 1913 was a banner year for Carson not only because of the strike, but because the first of the fiddling conventions that would win local fame for him took place that year.

1913 was also the year of the murder of thirteen-year-old factory worker Mary Phagan. Carson’s commemorative ballad “Little Mary Phagan” caught fire, especially among mill workers outraged by the crime and by what they perceived as attempts by Phagan’s supervisor and suspected killer Leo Frank to buy his way out of responsibility for it. On the day of Frank’s 1915 lynching, Carson sang the song for a crowd gathered at the Marietta Courthouse until he was hoarse. The ability to express the feelings of displaced farmers made him a valuable tool for rurally oriented politicians such as Tom Watson and Eugene Talmadge. Performing at their rallies, Carson served as the symbol of the imagined lost virtues of an agrarian past.6 His local renown also made him a valuable commodity for the newly established WSB. In September 1922, he became the first country fiddler to appear on radio, afterward becoming such an on-air fixture that WSB broadcast a special program each year on his birthday.7

The idea of recording Carson originated with Polk Brockman, who ran the section of his grandfather’s Atlanta furniture store that sold phonographs and records. By 1921 the store – James K. Polk, Inc. – was the South’s largest outlet for the Okeh Record Company. Within a couple of years, however, under the onslaught of radio and more general economic problems, record sales lagged. In June 1923, while sitting in a New York theater, Brockman was inspired by a newsreel of a fiddlers’ contest in Virginia. In a memo pad he jotted, “Fiddlin’ John Carson – local talent – let’s record.” Peer approved the idea, and Brockman rented space on Nassau Street and invited Carson and a number of acts to participate. No one in the makeshift studio that day could have anticipated the cultural phenomenon they were launching.8In the months and years following Carson’s success, other local notables such as Riley Puckett and Gid Tanner made recordings in Atlanta, as did famed out-of-towners such as Jimmie Rodgers, the Carter Family, and Bill Monroe. While country music recording sessions occurred in other locales during the 1920s, Atlanta, with its powerful radio station and rich vein of local talent, was foremost. As one music historian observes, “Most of the genuine country music recorded in the 1920s came from Atlanta. It was the Nashville of its day, and all the major record companies had studios there.”9

However, these developments passed beneath the notice of Atlanta’s social and civic elite. For decades the city’s leaders had hungered to make Atlanta a southern Mecca of cultural activity, but their notions of what constituted “culture” were far too restricted to allow for the efforts of a Gid Tanner or a Fiddlin’ John Carson.

For their part, the newspapers portrayed the hillbillies, when they considered them at all, as they had pictured the participants in the city’s fiddling conventions – as quaint and colorful relics of a simpler past, rather than as creative forces in their own right or as harbingers of new forms of cultural expression.

A Lost Opportunity

Though the city’s respectable citizens might have been oblivious, these hillbilly and “race” (African American) artists effected a major shift in Atlanta’s cultural role. Prior to the 1920s, Atlanta had always served as a funnel into the South for culture produced elsewhere, whether in New York, Hollywood or Europe. But in 1922 the situation began to reverse. Through the broadcasting power of WSB and the portable recording machines of northeastern engineers, Atlanta began to funnel regional musical culture out to the rest of the country, where its lasting significance was much greater than that of anything the city had previously produced along cultural lines.

Atlanta’s prominence was not to last. In January 1927, WSB officially affiliated with the NBC radio network. Henceforth network programming would leave less airtime for local talent, and a new sense of cosmopolitan sophistication may have altered the attitudes of WSB officials toward the station’s more rustic offerings.10 In any event, as one chronicler has noted, “The era in which a fiddler or banjo picker could drop by the station and go on the air on short notice had now ended.”11 What apathy and respectability did not finish off, desperate economic times did. The Great Depression laid waste to the recording industry. Most labels discontinued recording sessions in the South, and some, including Okeh, went out of business altogether.

By the time the recording business rebounded, Atlanta’s day in the sun had passed. But the country music and blues industries that Atlanta had helped launch firmly established themselves elsewhere and profoundly influenced other American musical forms, thereby playing an essential role in molding the American popular culture that swept the globe during the twentieth century.12 Atlanta’s contribution to this phenomenon was admittedly limited, but it was crucial and is worthy of greater acknowledgment. Perhaps endowing landmark status on an unprepossessing old building on Nassau Street would be a good first step.

Learn about Blind Willie McTell, Enrico Caruso, John Philip Sousa, Bessie Smith, Geraldine Farrar, and other artists who, with John Carson, participated in conflicts over issues of taste, aesthetics, social status, and Atlanta’s place in the nation’s cultural landscape in Steve Goodson’s Highbrows, Hillbillies, and Hellfire. Thanks to the University of Georgia Press for permission to publish this essay, adapted from the book.

Citation: Goodson, Steve. “‘The Nashville of its Day’: Recalling the Origins of Recorded Country Music in 1920s Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. August 09, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20170809.

Notes

- Associated Press, “Atlanta Building Steeped in Music History Faces Demolition,” New York Times, August 8, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2017/08/08/us/ap-us-country-music-landmark-atlanta.html; Associated Press, “Atlanta Building Steeped in Music History Faces Demolition,” Washington Post, August 8, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/atlanta-building-steeped-in-music-history-faces-demolition/2017/08/08/14b024aa-7c4d-11e7-b2b1-aeba62854dfa_story.html?utm_term=.2201b8959f43; Associated Press, “Atlanta Building Steeped in Music History Faces Demolition,” US News, August 8. 2017, https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/georgia/articles/2017-08-08/atlanta-building-steeped-in-music-history-faces-demolition; Associated Press, “Atlanta Building Steeped in Music History Faces Demolition,” ABC News, August 8, 2017, http://abcnews.go.com/Entertainment/wireStory/atlanta-building-steeped-music-history-faces-demolition-49095220; Associated Press, “Atlanta Building Steeped in Music History Faces Demolition,” Yahoo Music, August 8, 2017, https://www.yahoo.com/music/atlanta-building-steeped-music-history-faces-demolition-151700548.html.[↩]

- Steve Goodson, Highbrows, Hillbillies, and Hellfire: Public Entertainment in Atlanta, 1880–1930 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002).[↩]

- Gene Wiggins, Fiddlin’ Georgia Crazy: Fiddlin’ John Carson, His Real World, and the World of His Songs (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 69, 80–81; Wayne D. Daniel, Pickin’ on Peachtree: A History of Country Music in Atlanta, Georgia (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990), 48–89. For examples of this early mixing of performers and styles, see Atlanta Journal, December 31, 1924 and July 12, 1925.[↩]

- Daniel, Pickin’ On Peachtree, 10–12.[↩]

- Bill C. Malone, Singing Cowboys and Musical Mountaineers: Southern Culture and the Roots of Country Music (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993), 64; Wiggins, Fiddlin’ Georgia Crazy, 74–76; Daniel, Pickin’ on Peachtree, 93; Archie Green, “Hillbilly Music: Source and Symbol,” Journal of American Folklore 78, 309 (July–September 1965): 208; Norm Cohen, “Early Pioneers,” in Stars of Country Music: Uncle Dave Macon to Johnny Rodriguez, edited by Bill C. Malone and Judith McCulloh (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975), 11–21. Daniel gives the recording date as June 14, but Wiggins in his discography claims that the session took place on June 19. Wiggins also states that despite subsequent interpretations of his famous “pluperfect awful” comment, Peer was likely more dissatisfied with technical aspects of the recordings than with Carson’s performance (75). The flip side of the record was “The Old Hen Cackled and the Rooster’s Going to Crow.”[↩]

- This biographical information is drawn from Wiggins, Fiddlin’ Georgia Crazy, xii, chap. 2, 128–29; John A. Burrison, “Fiddlers in the Alley: Atlanta as an Early Country Music Center,” Atlanta Historical Bulletin 21, no. 2 (Summer 1977): 70; Cohen “Early Pioneers”: 16–17; Daniel, Pickin’ on Peachtree, 87–96.[↩]

- Burrison, “Fiddlers in the Alley,” 70. See also Green, “Hillbilly Music,” 209; Daniel, Pickin’ On Peacthree, 50, 93.[↩]

- Green “Hillbilly Music,” 208; Wiggins, Fiddlin’ Georgia Crazy, 74–75; Burrison, “Fiddlers in the Alley,” 70–72.[↩]

- Daniel, Pickin’ on Peachtree, 69. The quote, cited in Daniel, is from Charles K. Wolfe, Tennessee Strings (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1977), 43. For more on local Atlanta artists, see Daniel, especially chap. 4; Cohen, “Early Pioneers,” 27–34.[↩]

- Daniel, Pickin’ on Peachtree, 65–66.[↩]

- Ibid., 66.[↩]

- For a book-length treatment of the influence of southern musical forms, see Bill C. Malone, Southern Music, American Music (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1979).[↩]