On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, a Black man living in Minneapolis, Minnesota, was killed by a white police officer, triggering what may have been the largest mass movement in U.S. history with between 15 and 26 million Americans participating, forcing a reexamination of the urban governance strategy known as, “The Atlanta Way.”

Four days after Floyd’s death1, a protest in downtown Atlanta developed into a riot2 and widespread looting. According to the city’s leading newspaper, this posed a “challenge” to the “Atlanta Way” – “an oft-repeated phrase used as an example of how Atlanta, led by the black and white business class, has often been able to come together on racial issues.”3 The media and Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms presented incidents of rioting that unfolded in Atlanta during summer 2020 as an unprecedented shift in the city’s recent past – an assumption that relies on the erasure of the long history of Black rebellion and white supremacist violence. In this article, we argue for a reconceptualization of the Atlanta Way. Emerging at the beginning of the 20th century, this urban governance strategy is constituted by state repression of Black urban rebellion and the use of Black authority figures to mediate between the state and social movements and to divide protestors.

This “divide and conquer” strategy adapts to emerging social conditions and relies on historical and current imaginaries that present Atlanta as “the city too busy to hate” and a “Black Mecca.” We examine the existing literature on the Atlanta Way, tracing its emergence to the 1906 massacre of Black Atlantans by white Atlantans, commonly referred to as the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot, and ending with an examination of two key events in the 2020 George Floyd uprising. This demonstrates the centrality of repression, mediation, and division to the Atlanta Way and reveals how this urban governance strategy has adapted over time to manage Black rebellion and foster an agreeable environment for capital accumulation.

The Atlanta Way: A Biracial Regime

The Atlanta Way refers to a mid-20th-century strategy of urban governance that stresses cooperation between Black and white political and business elites. Floyd Hunter first shed light on the structure of governance in Atlanta in the mid-20th century by documenting and analyzing the process of formal and informal negotiations among the city’s most influential decision-makers.4 Hunter reveals that white politicians who needed the support of Black voters in the 1940s and early 1950s included Black community leaders, who had been banned from formal planning spaces, in governance only through informal negotiations.5

Scholarship calls attention to the efficacy of this strategy in the mid-20th century in accomplishing desegregation without the intensity of white violence occurring elsewhere in the country. Kevin Kruse explains that desegregation was orchestrated through careful negotiations between white politicians and officials, namely Mayor William B. Hartsfield, who saw overt white supremacy as bad for business, and Black community leaders, particularly ministers.6 Wishing to avoid white backlash, Black leaders emphasized incremental progress and urged Black residents to practice restraint to ease whites into integration. At the same time, white politicians stressed the potential for economic progress accompanying desegregation.7 This approach to desegregation, along with an intentional campaign by city politicians to attract capital investment, resulted in an image of Atlanta as the “city too busy to hate,” first coined by Mayor Hartsfield in 1959.8

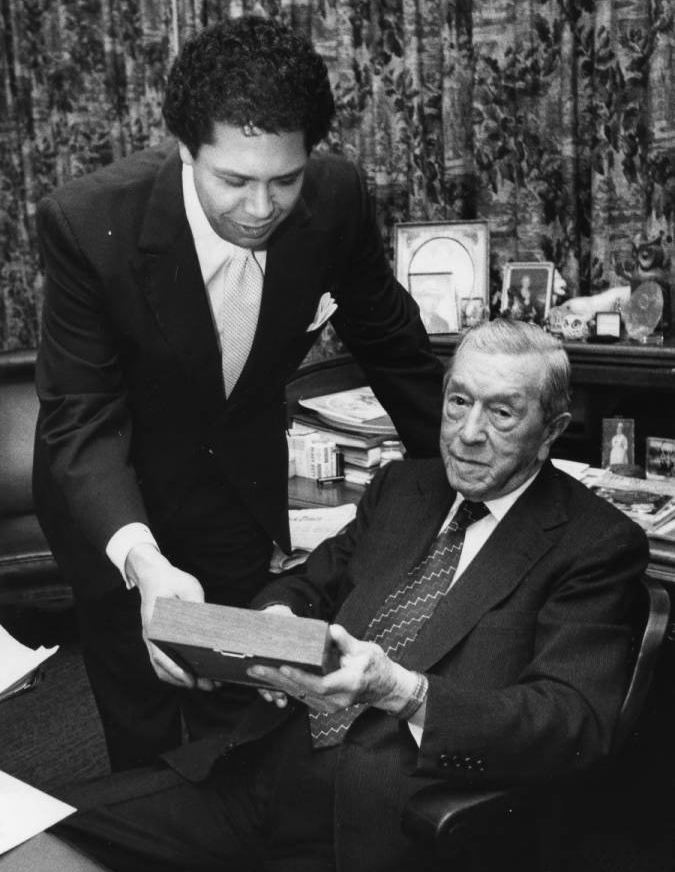

Clarence Stone and Larry Keating both argue that the domination of city politics by white, wealthy business leaders from the 1940s through the 1970s depended on support from Black political and community leaders, laying the foundation for ongoing biracial coalitional politics.9 As Atlanta’s demographics shifted during decades of white flight, the formal domination of white politicians gave way in the 1970s to the ascendancy of Black politicians in key offices. This included the election of the first Black mayor of Atlanta, Maynard Jackson. This adaptation allowed for the “Black Mecca” imaginary to proliferate among Black inhabitants and outsiders. Keating explores the continuation of coalitional politics in this period. Initially, Mayor Jackson attempted to govern with the support of a new coalition, including Black residents of multiple classes and urban liberal whites. However, as white businesses became increasingly hostile to him, he shifted strategies to remake the prior biracial coalition of white business interests and middle-class Black community leaders.10 Stone, writing in 1989, refers to this coalition as an urban “regime” of Black and white civic leaders, business elites, and politicians cooperating to create favorable conditions for capital investment in the city, while stressing steady progress towards racial equality through economic development.11

Bruce Dixon, activist-journalist of Black Agenda Report, popularized the phrase “black misleadership class” to describe an “actual and aspirational class, which ultimately sees its interests as tied to those of U.S. imperialism and its ruling circles.”12 Dixon argued that as the era of Black Power, the Civil Rights Movement, and Keynesianism came to a close, “the demand for societal economic justice was replaced by the quest for ‘community economic development,’ which usually meant creating black millionaires” in the hope that consolidation of wealth would improve the material conditions of all Black residents.13

Scholar Adolph Reed Jr. argued in 1979 that Black struggle in the long 1960s was managed by the professional class to restructure capitalism, allowing Black elites to grow qualitatively and quantitatively and positioning those elites as “leaders” representative of a homogenous Black constituency.14

In Atlanta, Black elites – many of whom gained popularity as Civil Rights activists – secured formal political power and economic benefits. They subsequently found themselves upholding the Atlanta Way by suppressing militant rebellion from working-class and low-income Blacks.

Mythology of the “City Too Busy to Hate” and the “Black Mecca”

The Atlanta Way’s legitimacy is undergirded by the image of a “Black Mecca” which has fostered Black political, economic, and social equity inside a “city too busy to hate” that has successfully curbed white power. However, neither imaginary stands up to closer scrutiny.15 Scholars have drawn attention to 20th-century incidents and processes of white supremacist violence, calling into question the myth of white tolerance. Following formal desegregation, the city externally propagated an image of tolerance. However, the city was internally experiencing a withdrawal of political, social, and financial support from whites. They felt abandoned by white elites, who they believed had given “white” public spaces to Black residents.16 Kruse explores how a mass exodus of white residents fleeing to the suburbs to establish predominantly white, largely privatized communities enabled white working- and middle-classes to withdraw from public spaces.17 While Atlanta largely avoided the most overt acts of white supremacist violence, whites enacted a slower economic violence in numerous ways, such as: by campaigning against the use of public funds for public space, petitioning to close public facilities such as neighborhood pools, and fighting for “local control” of suburban communities’ property taxes. These actions enabled whites to create private communities with class and racial homogeneity, while gutting the city of tax revenue.18

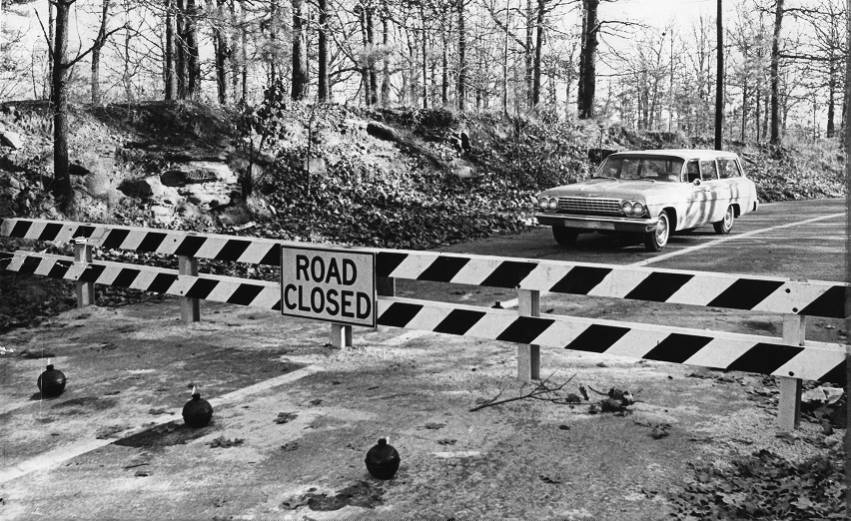

Overt acts of white supremacist violence were not absent during desegregation. Blau and Michney detail the white supremacist bombing of a Black elementary school in 1960, just months before the desegregation of Atlanta’s public schools. Following this event, Mayor Hartsfield quickly moved to situate the bombers as outsiders. He did so despite the context of nineteen other racially-motivated bombings occurring inside city limits in the thirteen years prior. He also did so within the context of Fulton County granting permits to two new Ku Klux Klan chapters in that year.19 Two years later, Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. set up roadblocks in Peyton Forest to separate the white and Black sides of the neighborhood; the national press condemned the act, while Klansmen rallied in support and Black activists campaigned against the barrier.20

Further, whites have maintained segregation through other means into the 21st century. In 1952, the city annexed the affluent Buckhead area north of the city in a mutually beneficial “gentlemen’s agreement:” the city gained white voters to maintain white political power and the Buckhead business elite gained influence over Atlanta’s tax policy.21 Buckhead maintained its racial homogeneity for several decades. This was in part through a preexisting arrangement in which white political leaders agreed to support the expansion of residential areas for Blacks to the west of the city, and also as Black business and community leaders agreed not to settle on the north side, including in Buckhead.22 In the early 2000s, however, the East Village bar district in Buckhead began to attract an increasing number of Black youths, athletes, and celebrities.23 Hankins, Cochran and Derickson uncover how a coalition of white elites effectively recreated Buckhead as a space of racial and economic exclusion. Organized groups harassed the clubs by reporting code violations, lobbied for restricted business hours, installed security cameras, and finally hired a developer to replace the bars with luxury shopping to decrease the percentage of Black people present in Buckhead.24

A myth of economic equality, which erases the ongoing economic violence against Black inhabitants, also legitimizes the Atlanta Way. Research reveals the gap between expectations of economic progress of Black Atlantans and the reality of persistent class and racial inequality. Sjoquist coins this the “Atlanta Paradox,”25 a moniker which itself obfuscates the reality that the business class and elite accumulate wealth from their counterparts’ impoverishment. Godshalk demonstrates that despite the city’s continued reputation as the “Black Mecca” for the Black middle class, it remains highly segregated and, as recently as 2019, Atlanta was ranked as the city with the highest income inequality in the country.26 Through an analysis of per capita income, Jaret reveals that Atlanta’s reputation as one of the best places for Black economic achievement or improvement is unsupported, and in fact income for Black residents has virtually stalled since 1980.27 Similarly, Hobson argues that Atlanta’s governance coalition continuously pushes for business-friendly politics that largely benefits local middle and upper classes and business interests in general. This contributes to deepening class and racial inequalities.28 For instance, the bid for the 1996 Olympics instigated cooperation between white business elites and Black city government officials on policies of urban renewal and gentrification to prepare Atlanta for the games.29 Keating argues that the city prioritizes investment in profitable projects over investment in low-income infrastructural projects. This places responsibility on business-driven public policy geared towards conventioneers, tourists, national and international sports fans, and new middle- and upper-class residents that have benefited outsiders instead of existing residents.30

A Lineage of Repression, Mediation, and Division

Scholars have previously pointed to the origins of the Atlanta Way in the wake of the 1906 massacre of Black Atlantans by white Atlantans, commonly referred to as the 1906 Atlanta race riot.31 We concur that the 1906 massacre is a formative event in the Atlanta Way and we locate repression, mediation, and division of Black resistance as essential to Atlanta’s urban governance strategy. One can observe these constitutive tactics throughout the 20th century to today, as they have adapted over time to social, political, and economic changes.

Decades preceding formal Black political power in Atlanta, a debate between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois revealed diverging strategies for racial equity. Booker T. Washington, in his Atlanta Exposition Address of 1895, urged Blacks to submit to white racial political rule and urged whites to provide employment, education, and legal protections to Southern Blacks.32 Referred to by W.E.B. Du Bois as the “Atlanta compromise,” this conservative accommodationist approach to economic and social safety for Blacks was rejected by Du Bois and challenged by the 1906 massacre.33 On September 22, 1906, a mob of thousands of white civilians attacked Black civilians, starting from downtown and spreading throughout the city over multiple days.34 Throughout the bloody few days, the militia and police focused more on harassing and disarming Black residents engaged in self-defense instead of suppressing the white uprising.35 Black residents, keenly aware of the values and loyalties of the police and state militia, individually and collectively defended themselves from the violence. In an area known as Dark Town (now Sweet Auburn and Downtown), Black residents successfully warded off a white mob on the second day by turning off the lights in their shanties and firing into the crowd of white men to scatter them.36 On the third day of violence, white policemen and deputized white civilians invaded another area known as Brownsville (now South Atlanta) in response to rumors that Brownsville residents were planning a retaliatory attack.37 After a shootout led to the death of a white policeman, police officers and state-sanctioned militia members raided homes in Brownsville the next day. They arrested 250 Black men and marched approximately 70 of them through the streets to the downtown jail on weapons or murder chargers. During the two-day assault on Brownsville, police or militia killed five Black civilians. Importantly, the repression of self-defense of Black residents by state forces is a part of the story of white violence in September 1906. Notably, Black Atlantans of all social classes defended themselves, whether by guarding their homes with pistols or organizing to repel white mobs.38

The story of 1906 also involves a shift in white elites’ strategy for interracial cooperation. While the white ruling class initially remained silent in response to the pogrom, the twin threats of economic decline and Black self-defense spurred white business and civic leaders to call on Black ministers, journalists, and businessmen. They did so in both open and closed meetings to temper the “disorderly” actors and direct them back to work and towards “law and order.”39 Black elites distanced themselves from low-income and working-classes with whom they had cooperated to defend themselves during the pogrom. For example, William F. Penn, Black physician and Yale graduate, responded to promises of protection by assuring that he and other Black men would help suppress disorder and protect white women from crimes committed by the “criminal classes.” 40 The decision by elite Black community leaders to serve as mediators for white politicians in the immediate aftermath of the massacre laid the template for protecting the city’s reputation and maintaining law and order. At the same time it forestalled the immediate racial justice that Black Atlantans demanded, especially working-class and low-income residents.41 This history suggests earlier origins of the Atlanta Way as a strategy of cross-racial, upper-class cooperation for economic development and illuminates an early example of repression of direct forms of Black defense post-Emancipation.

These trends continued throughout the 20th century as the most threatening aspects of Black-led social movements were met with state repression. At the same time, campaigns for moderate racial and economic progress through less disruptive tactics were encouraged. Atlanta’s governing coalition relied on its Black middle-class leaders to preserve order among the threat of urban unrest by managing campaigns for civil rights during the 1950s and 1960s.42 During Atlanta’s bus desegregation campaign, for instance, Black ministers worked closely with the mayor and urged moderation, asking Black bus riders to avoid sitting by whites, including after legal desegregation.43

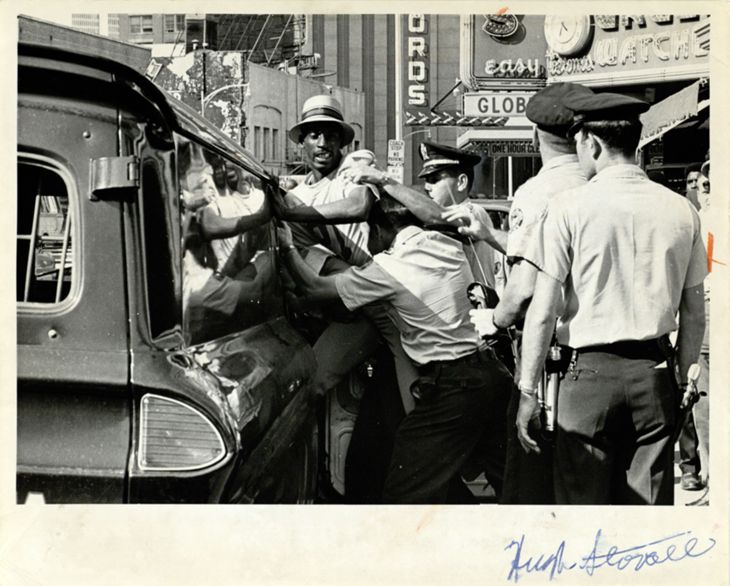

Incidents of police brutality and resulting riots that erupted in majority-Black working-class and low-income Atlanta neighborhoods in 1966 and 1967, while not as widespread and sustained as in other U.S. cities at the time, tarnished Atlanta’s image as a hub for racial harmony. They also revealed the tensions between factions of Black activists and civil leaders.44 After a years-long urban renewal program that razed a housing project and built a major sports stadium, displacing over 900 Black families and pushing 10,000 people into 354 acres, in September 1966, a police officer shot Black resident, Harold Prather, as he allegedly resisted arrest in the Summerhill neighborhood. Already feeling angry and despaired from urban renewal policies that disadvantaged them, a crowd of over a thousand residents “rocked cars, threw bricks and bottles, and threatened to harm [Mayor] Allen and the police and to destroy the stadium.”45

The city’s full police force of 750 officers fired warning shots and tear gas on the crowd, while over 300 officers protected the new stadium.46 Ralph D. Abernathy, civil rights activist and minister, suggested the protestors be taken to the stadium for their complaints to be heard, while other Black ministers and politicians urged calm and nonviolence. In the aftermath of the riot, mainstream media and politicians, both white and Black, attempted to marginalize the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) by pinning the riot on these young activists.47

Just nine months later in the Dixie Hills neighborhood, Black youths clashed with a security guard outside a restaurant, prompting residents to call for a town hall to address that issue, as well as poor sanitation services and a lack of playgrounds.48 Two days later, police shot a Black youth, prompting Black politicians at a Dixie Hills meeting to call on the crowd to petition the city. Stokely Carmichael and other members of SNCC and other grassroots organizations largely ignored their suggestions, however, and instead called on people to take to the streets. The police fired warning shots as the crowd threw bottles and rocks at police cars.49 Having learned from the Summerhill incident, the city administration paired concessions with overt repression. The next morning, construction began on several playgrounds in the neighborhood and Mayor Allen announced the Negro Youth Patrol, “a volunteer group that would monitor the activities of the neighborhood’s young people throughout the remainder of the summer.”50 Simultaneously, the police chief deployed hundreds of officers to Dixie Hills. Organizers of SNCC condemned the Youth Patrol and called for residents to resist the entrance of cops and whites into the neighborhood. In response, 300 police officers faced down the 200 protestors, responding with gunfire that killed one man and injured three others, including a child. After this event, the Dixie Hills rebellion quieted, and Black moderates circulated a petition to expel SNCC activists.51

Beyond these two rebellions, during this period regular police presence, curfews, and frequent arrests repressed the more militant wing of the movement for human rights. They also maintained an image of Atlanta as a modern, global, economically viable city of “the New South”.52 Further, the city administration and police used the growing divide between moderate and radical Black activists. In 1968, as riots rocked cities across America after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Atlanta city officials carefully managed the possibility of Black rebellion in the city. Working closely with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and other civil rights and neighborhood-based groups, Atlanta city officials urged calm, while simultaneously deploying every single police officer on the day of the funeral procession.53

The Atlanta Way continued to evolve after some demands for desegregation and voting rights had been met and as Black working-class and low-income Atlanta residents continued to fight back against the effects of racial capitalism. In 1981, during an epidemic of murders targeting Black children and youth, Black residents of Techwood Homes public housing project and the area, who felt that the city was failing to protect them from this violence, brandished weapons and patrolled the neighborhood.54 In response, the city, now governed by a Black mayor, arrested multiple organizers on weapons charges.55 The following day, the number of volunteers for the patrol doubled. They continued to patrol the housing project with baseball bats, despite warnings from Mayor Jackson and other high-ranking officials.56 Beyond aggressively repressing patrol participants, the city sanctioned an alternative patrol composed of unarmed volunteers, called the Watch Patrol.57 Another group, the Committee to Stop Children’s Murders (STOP Committee), also formed in response to the Atlanta child murders. Seven mothers of slain and missing Atlanta children founded the group. One of the groups most outspoken leaders, Camille Bell, was known for her rebuke of the Black elitism that she claimed ruled the city. Bell stated that Mayor Jackson had misrepresented their children as “hoodlums” and that folks such as Coretta Scott King had “double-crossed” the organized mothers.58 While initially supportive of the STOP Committee, Mayor Jackson’s administration switched gears in the face of criticism and the Georgia Office of Consumer Affairs investigated the group’s finances.59 The repression of Black protests continued, including during Jackson’s second term. In 1992, riots broke out in multiple Atlanta neighborhoods following the acquittal of the police officer who had beaten Rodney King in Los Angeles, California.60 On Atlanta’s west side, police indiscriminately dropped tear gas from an airplane to disperse the riot, as multiple police agencies cooperated to quickly suppress the uprising on the ground.61

A fuller picture of the Atlanta Way of governance requires an understanding of how the city has relied on policing to suppress more common “deviant” behavior that might threaten economic development. Wiggins argues that preemptive policing tactics were first developed in Atlanta on the largely Black working-class and low-income residents. By the end of the 1960s, Atlanta, similar to many other urban areas, experienced rising crime rates and economic decline in the urban core.62 In response, Atlanta’s Black political leaders, supported by both Black and white business leaders, promoted punitive crime control policies. These included foot patrols, public decency legislation, and the expansion of police powers in low-income urban neighborhoods.63 This approach to policing, which stresses orderliness and respectability, prefigured the rise of order-maintenance or “broken windows” policing elsewhere in the country.64 Distinct from their counterparts in other cities who argued that disorder caused crime, Maynard Jackson and Black business owners linked orderliness and respectability with their survival and wealth by arguing that “derelicts” and disorderly behavior limited economic development for Black Atlantans. The effect, however, was the same; victimless crimes, such as prostitution and public drunkenness, were prioritized to make spaces safe for development.65

This history suggests that repression, mediation, and division are constitutive elements of the Atlanta Way. Yet, despite these instances of urban unrest and the ongoing suppression of Black working-class and low-income inhabitants, the image of Atlanta as the “city too busy to hate” and the “Black Mecca” has combined with the promotion of non-violent civil disobedience or electoral routes as the acceptable strategies for progress to create a powerful legend about Atlanta’s peaceful role in social change. Consequently, incidents of urban unrest, such as the riots in 1966, 1967, and 1992, as well as the state repression that followed, are sometimes omitted from or obscured in the story of Atlanta. In summer 2020, when a Black-led mass movement occasionally erupted into more militant or “deviant” forms of resistance, the Atlanta Way again revealed itself precisely through the city’s attempts to divide, repress, and obscure militant struggle.

The Atlanta Way in the George Floyd Uprising

On May 29, 2020, thousands of people poured into Centennial Olympic Park for a protest against police brutality, sparked by police officers’ murder of George Floyd just a few days prior, and the resulting protests and rioting in Minneapolis. What began as a relatively tame march through downtown Atlanta escalated into a riot when the police began antagonizing and assaulting protesters with chemical weapons.66 A large and determined multi-racial crowd set fire to unoccupied cop cars and methodically destroyed the glass façade of the CNN center with explosives before entering the building.67 Some rioters broke into businesses on Marietta Street and during the long night, a crowd moved towards Buckhead – an important site of segregated wealth with a history of racialized conflict68 – where they looted luxury shopping malls Phipps Plaza and Lenox Square. The rioters caused $10 to $15 million dollars in damage in Buckhead within the span of hours.69 That night, Georgia Governor Brian Kemp deployed 1,000 National Guard troops to Fulton County with a large contingent centered around the CNN building and Centennial Park where the protests began and another around the Governor’s Mansion.70 The National Guard remained deployed in Atlanta for several months thereafter.71

As rioting unfolded that first night, Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms appeared for an emergency press conference. She told protestors to “go home,” to stop “disgracing our city,” and to instead “show up at the polls on June 9th” or in November to voice concerns.72 While her chief-of-police stood behind her, the mayor also said that she could not protect the protestors from what might happen to them in the streets, just as she could not protect her own Black son from violence – referencing the many deaths of Black boys and men at the hands of police.73 Atlanta rapper and business owner, T.I., then took to the podium, stating that at the end of the day, you might not get “treated right” in places like New York, Los Angeles, Detroit, or Alabama, but that “Atlanta has always been here for us” – referencing the mythology of the Black Mecca. Another Atlanta based rapper and business owner, Killer Mike, then tearfully said, “It is your duty not to burn your own house down,” while wearing a shirt adorned with the phrase, “Kill Your Masters.”74

Much like preceding mayors and state-anointed community leaders, Mayor Bottoms, T.I., and Killer Mike each referenced the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement by conjuring local figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Andrew Young.75 In the 2014–2016 wave of Black Lives Matter protests, Mayor Kasim Reed also evoked King, contrasting the behavior of modern day protests with that of the Civil Rights icon and arguing that the airing of grievances must be done in a “King-ian fashion.”76 The conjuring of King in moments of turmoil can be seen as an attempt by Atlanta’s Black upper class to reassert the hegemony of the Atlanta Way. It is an external call for non-Atlantans to retain the idea of progress supposed in the city’s history, as well as an internal admonishment to Atlantans about proper forms of protest.77 As the Atlanta police force tear gassed and arrested protestors, Mayor Bottoms stood in front of the police chief, whom she supervises, to state that she was unable to protect her citizens from police violence. While acknowledging Black residents’ experiences of violence, Mayor Bottoms at the same time denied any power over the city’s police who receive one-third of the city’s budget.78 By obscuring the power that she has as mayor and her heightened abilities as a state actor to protect her son, Mayor Bottoms deployed the identity-based argument that lies at the core of the Atlanta Way: regardless of class and power position, all Black people share the same fate.79 As Atlanta activist and writer Devyn Springer notes, “when the ‘we’ is meant to be Black people, then it must be made clear that most of ‘us’ do not own this city, even if it was built by our forced labor in generations past.”80 This method of mediation relies on class-blind narratives from state-appointed authorities – once pastors and now rappers – who are deployed in moments of crisis.

Protest Press Conference, Atlanta, Georgia, May 29, 2020. Source: Atlanta Police Department.

The Myth of (White) Outsiders

As the second week of the 2020 summer Atlanta protests concluded, a white Atlanta police officer shot and killed a Black man named Rayshard Brooks in a South Atlanta Wendy’s parking lot.81 Within hours, protestors blocked off the Wendy’s entrance with cars, barring workers and customers alike, and setting into motion what would become a weeks-long protest and occupation of the Wendy’s parking lot.82 Less than twenty-four hours after a policeman shot and killed Brooks, protestors burned down the restaurant where he died. In the weeks after Brooks’s death, protestors demanded a peace center at the site of the former Wendy’s as the Georgia Bureau of Investigation and local law enforcement cooperated to find those suspected of burning down the Wendy’s. 83

A week after the arson, law enforcement circulated posters depicting some of the alleged protestors connected to the fire. Most of the images contained pixelated freeze frames of people in front of the fast-food chain’s charred structure.84 Some frames were of whites, while others showed Blacks. Some of the people in the frames had their faces completely hidden, while others were visible. One emerging wanted poster was very clear; it showed an image from surveillance footage of a white woman in a convenience store with the identifying name of Natalie White.85 In the footage that the GBI released of the final moments before Brooks’s death, Brooks identifies White as his girlfriend.86 The fact that Brooks was survived by a wife complicated this assertion. The Crime Stopper poster for White went viral, stirring allegations of an “outside agitator.” These allegations coincided with those of Police Chief Erika Shields that the protestors were “not Atlantans, but a highly calculated terrorist organization embedded inside the peaceful protestors.”87 White could be seen as an outsider in two ways: as a white woman in a Black-centered movement and as a white woman interfering with a Black marriage. White’s outsider status served as discursive evidence for the myth of Black nonviolence in Atlanta. On June 23, 2020, Mayor Bottoms, soon-to-be-senator Raphael Warnock, and Bernice King, daughter of Martin Luther King Jr., attended the funeral of Rayshard Brooks. Tyler Perry had funded the funeral, which took place at Ebenezer Baptist Church, the former pulpit of Martin Luther King Jr.88 During the funeral, police arrested Natalie White and booked her into the Fulton County Jail.89 Despite the lack of publicly accessible footage of White at the Wendy’s, she was the first and most publicized arrestee from the June 13th protest.

Despite fears of “outsiders” and “calculated terrorists” participating in the summer’s riots and protests, analysis of arrestees shows that the vast majority of participants were Black and Georgian.90 In the first two weeks of protests, law enforcement arrested approximately 600 people.91 They charged about half of those arrested with violating the curfew instated by Mayor Bottoms on the second night of protests and which lasted for over a week.92

Despite the fact that Atlanta protests quieted down towards the end of the summer, local and federal law enforcement have actively pursued Atlanta residents associated with those events, as recently as March 2021; some remain in jail due to denied bail.93

The events of summer 2020 have revealed the latest instantiation of the Atlanta Way: the city’s and the state’s use of overt violence and intimidation through the deployment of the National Guard for months, the instatement and enforcement of a citywide curfew, the use of chemical weapons during protests, the arrests of hundreds of protestors and the involvement of federal investigative forces and crowdsourcing to find other suspected protestors. On the other side of this strategy were more subtle but equally familiar tactics, such as the coordinated effort by Atlanta city officials and city-sanctioned spokespeople to portray those responsible for the damaging aspects of the movement as outsiders and the pressure for the aggrieved to use acceptable means of expression such as electoralism. These tactics of discursively dividing the movement, mediating through authority figures, and repressing the protests combine in an attempt to maintain Atlanta’s image as a racially-harmonious and economically-inviting city.

The Future of the Atlanta Way

We have argued for a reconceptualization of the Atlanta Way as an ongoing and adaptive state-sponsored strategy that first emerged from the 1906 massacre. The violent repression of subsequent Black-led rebellions against racial capitalism and state-appointed leaders who urged incrementalism and non-violence in order to divide social movements have reconstituted the Atlanta Way. Reconceptualizing the historical rise of biracial coalitional politics uncovers the adaptability of the Atlanta Way in the face of changing social conditions. The white power structure has negotiated with elite Blacks to allow the ascendancy of some to political and economic power, first informally then formally. Yet, the growth of Black elite power has secured the hegemony of the ruling elite and conditions of capital accumulation at the direct expense of working and low-income classes, particularly those who continue to fight for the rights of all Black Atlantans. As civic organizations have declined throughout the last several decades, the Atlanta Way has shifted to rely on new types of Black leaders to mediate between political elites and urban inhabitants demanding human rights.

Some have lauded this urban governance strategy for its success in preventing the property destruction and death that occurred in other U.S. cities in response to civil rights protests.94 However, this narrative obfuscates the constitutive presence of rebellion against racial inequality and ongoing state repression of such rebellion. Imaginaries play a key role in place-making. The (re)production of an image of Atlanta as “the city too busy to hate” and a “Black Mecca” seeks to attract the capital and social legitimacy required to sustain a biracial upper class and capital accumulation. Yet, as the working classes resist the conditions of oppression from which such accumulation derives, these very imaginaries – which obscure militant resistance and paint Atlanta as racially harmonious – work to limit the actual possibilities of resistance to racial capitalism.

Despite its resiliency, the Atlanta Way perpetuates its own duplicity in the form of a widening and deepening inequality among the city’s Black residents, some of whom live in a fictional “Wakanda” and others of whom live in despair. Just as organizations and radical activists in prior decades ruthlessly critiqued and openly challenged elite biracial rule, a new generation of activists and residents are indeed posing challenges to the Atlanta Way. This ranges from radical youth activists donning shirts with the phrase “Unlovable Brats” – after Civil Rights leader and two-term mayor Andrew Young referred to them as such in the wake of the 2016 Black Lives Matter protests – to the riots and occupation of 2020.95 Atlanta’s tale of biracial unity and upward economic progress for Black inhabitants may struggle to retain its hegemonic position as formal political processes fail to respond to the continued immiseration of Black working-class and low-income residents.

Cover Image Attribution: George Floyd Protests in Atlanta, Georgia, June 19, 2020. Photograph by John Ramspott. SOURCE: Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons License Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC By 2.0).

Citation: Edgett, Kayla and Sarah Abdelaziz. “The Atlanta Way: Repression, Mediation, and Division of Black Resistance from 1906 to the 2020 George Floyd Uprising.” Atlanta Studies. October 20, 2021. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20211020.

Kayla Edgett is an Atlanta-based community organizer and graduate student of geography in the Department of Geosciences at Georgia State University. Her activism and research focus on place, race, class, and resistance to racial capitalism. She is co-founder of the annual Atlanta Radical Book Fair at Auburn Avenue Research Library. Email Kayla at kayla.edgett@gmail.com.

Sarah Abdelaziz is a community organizer based in Atlanta and with roots in the Global South. They are currently the Director of the Activist in Residence program at Abolitionist Teaching Network. Sarah’s organizing spans the course of 10 years and focuses on the intersections of capitalism, abolition, race, and the self-determination of BIPOC & queer working-class people. Email Sarah at s.abdelaziz92@gmail.com.

Notes

- Larry Buchanan, Quoctrung Bui, and Jugal K. Patel, “Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History,” The New York Times, July 3, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html.[↩]

- We use the term “riot” to denote singular instances of property destruction and defensive violence against police. We recognize the racialized associations with the term and its loaded history of anti-blackness and fear-mongering. We reject these racially charged uses of the word and choose to use it for precision and accuracy to illuminate the activities associated with riots. We use the term “uprising” to refer to the widespread movement against police brutality in 2020, which included but was not limited to riots. Finally, we avoid referring to the 1906 white supremacist massacre in Atlanta as a “riot,” believing that the term erases the violence of this event and falsely equates property destruction with murder.[↩]

- Ernie Suggs and Rosalind Bentley, “Atlanta Way’ Challenged after Violent Night of Protest,” Atlanta Journal Constitution, May 31, 2020, accessed December 31, 2020, https://www.ajc.com/news/atlanta-way-challenged-after-violent-night-protests/HWsEwkX0ZN6xD4kesoElSO/.[↩]

- Floyd Hunter, Community Power Structure: A Study of Decision Makers (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1953).[↩]

- Floyd Hunter, “Power structure of a sub community,” in Community Power Structure: A Study of Decision Makers. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1953), 113–147.[↩]

- Kevin M. Kruse, “The Politics of Race and Public Space: Desegregation, Privatization, and the Tax Revolt in Atlanta,” Journal of Urban History 31, no. 5 (July 2005): 610–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144205275732.[↩]

- Kruse, “The Politics of Race and Public Space.”[↩]

- Kevin M. Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. (Princeton, NJ; Oxford, England: Princeton University Press, 2005); Charles Rutheiser, Imagineering Atlanta: The Politics of Place in the City of Dreams. (London and New York: Verso, 1996).[↩]

- Clarence N. Stone, Regime Politics: Governing Atlanta, 1946–1988. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1989); Larry Keating, Atlanta: Race, Class, and Urban Expansion (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2001).[↩]

- Keating, Atlanta.[↩]

- Stone, Regime Politics.[↩]

- Glen Ford, “The Validity and Usefulness of the Term ‘Black Misleadership Class,’” Black Agenda Report, January 4, 2018.[↩]

- Bruce Dixon, “Failure of the Black Misleadership Class,” Black Commentator, February 7, 2006.[↩]

- Adolph L. Reed, Jr., “Black Particularity Reconsidered,” Telos no. 39 (1979): 71–93, https://doi:10.3817/0379039071,[↩]

- For an historical account of the role of imaginaries in the making of Atlanta see Charles Rutheiser, Imagineering Atlanta.[↩]

- Kruse, “The Politics of Race and Public Space”; Michan Andrew Connor, “Metropolitan Secession and the Space of Color-Blind Racism in Atlanta,” Journal of Urban Affairs, 37:4 (2015): 436–461, DOI: 10.1111/juaf.12101.[↩]

- Kruse, “The Politics of Race and Public Space.”[↩]

- Kruse, “The Politics of Race and Public Space.”[↩]

- Blau, Max and Todd Michney, “Terror in the City Too Busy to Hate: How the English Avenue School Bombing Challenged Atlanta’s Popular Myth of Racial Progress,” Atlanta Studies (December 12, 2020), https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20201212.[↩]

- Kruse, White Flight.[↩]

- Connor, “Metropolitan Secession.”; Stone, Regime Politics.[↩]

- Katherine B. Hankins, Robert Cochran and Kate Driscoll Derickson, “Making Space, Making Race: Reconstituting White Privilege in Buckhead, Atlanta,” Social & Cultural Geography 13, no. 4 (2012): 379–397.[↩]

- Hankins, Cochran, Derickson, “Making Space, Making Race.”[↩]

- Hankins, Cochran, Derickson, “Making Space, Making Race.”[↩]

- David. L. Sjoquist, The Atlanta Paradox (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2002); David F. Godshalk, Veiled Visions: The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot and the Reshaping of American Race Relations (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006).[↩]

- Wei Lu and Alexandre Tanzi, “In America’s Most Unequal City, Top Households Rake in $663,000,” Bloomberg, November 2, 2019.[↩]

- Charles Jaret, “Black Internal Migration and Inter-Racial Socioeconomic Inequality in Atlanta and Other Metropolitan Areas: Has It Changed in the Past 35 Years?” The Journal of Public and Professional Sociology 11, no. 1 (2019), https://doi.org/10.32727/12.2019.7.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca.[↩]

- Larry Keating, Atlanta: Race, Class, and Urban Expansion. (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2001).[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca, 6; Godshalk, Veiled Visions.[↩]

- Joanne Grant, “Part IV: The 20th Century” in Black Protest: History, Documents, and Analyses; 1619 to the Present (New York: Fawcett Premier, 1986), 175–214.[↩]

- Godshalk, Veiled Visions; Clarissa Myrick-Harris, “The Origins of The Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta, 1880-1910,” Perspectives on History (2006), https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/november-2006/the-origins-of-the-civil-rights-movement-in-atlanta-1880-1910.[↩]

- Godshalk, Veiled Visions.[↩]

- Godshalk, Veiled Visions.[↩]

- Godshalk, Veiled Visions, 102.[↩]

- Godshalk, Veiled Visions.[↩]

- Godshalk, Veiled Visions, 100–105.[↩]

- Godshalk, Veiled Visions, 135–162.[↩]

- Godshalk, Veiled Visions, 139.[↩]

- Godshalk, Veiled Visions.[↩]

- Stone, Regime Politics.[↩]

- Kruse, “The Politics of Race and Public Space.”[↩]

- Tuck, Beyond Atlanta.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca, 46.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca, 46; Winston A. Grady-Willis, Challenging U.S. Apartheid: Atlanta and Black Struggles for Human Rights, 1960–1977 (Raleigh, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 114–119.[↩]

- Grady-Willis, Challenging U.S. Apartheid, 122–124.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca, 47.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca, 47.[↩]

- Grady-Willis, Challenging U.S. Apartheid, 130–132.[↩]

- Grady-Willis, Challenging U.S. Apartheid, 130–133.[↩]

- LeConté J. Dill, Orrianne Morrison, and Mercedez Dunn, “The Enduring Atlanta Compromise: Black Youth Contending with Home Foreclosures and School Closures in the ‘New South,’” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 13, no. 2 (2016): 365–77, doi:10.1017/S1742058X16000217.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca, 48.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca.[↩]

- Rhonda Cook, “Vigilante Group Begins Patrols, but Group Founder Arrested,” United Press International, March 21, 1981, https://www.upi.com/Archives/1981/03/21/Vigilante-group-begins-patrols-but-group-founder-arrested/2596353998800/.[↩]

- Cook, “Vigilante Group Begins Patrols”; Akira Drake Rodriguez, Diverging Space for Deviants: The Politics of Atlanta’s Public Housing (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2021), 154–158.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca, 120–121.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca, 110–117.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca.[↩]

- Danielle Wiggins, “‘Order as Well as Decency’: The Development of Order Maintenance Policing in Black Atlanta,” Journal of Urban History 46, no. 4 (2019): 711–727, https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144218822805.[↩]

- Wiggins, “Order as Well as Decency.”[↩]

- Wiggins, “Order as Well as Decency.”[↩]

- Wiggins, “Order as Well as Decency.”[↩]

- Ellen Elderidge and La’Raven Taylor, “Atlanta Protests Turn Violent: Police Cars, Local Restaurants Damaged,” GPB, May 29, 2020, https://www.gpb.org/news/2020/05/29/atlanta-protests-turn-violent-police-cars-local-restaurants-damaged.[↩]

- Fernando Alfonso, “CNN Center in Atlanta Damaged during Protests – CNN,” CNN, May 30, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/29/us/cnn-center-vandalized-protest-atlanta-destroyed/index.html.; Nick Valencia, “Violent George Floyd Protests at CNN Center Unfold Live on TV,” YouTube Video, 15:30, May 30, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yve9DhT8Nt4.[↩]

- Hankins, Cochran, Derickson, “Making Space, Making Race.”[↩]

- Andy Peters, “Buckhead Protest Damage Tabbed at $10 Million to $15 Million,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 2, 2020.[↩]

- Michael King, “Brian Kemp Extends Order Authorizing National Guard in Cities Through October 19th,” 11Alive, September 24, 2020.[↩]

- King, “Brian Kemp Extends Order.“[↩]

- Brynn Anderson, “Read Remarks from Mayor Bottoms, Killer Mike, And Others in Response to Protests Turned Destructive,” WABE News, May 30, 2020, https://www.wabe.org/read-remarks-from-mayor-bottoms-killer-mike-and-others-in-response-to-protests-turned-destructive/.[↩]

- MXGM, “Operation Ghetto Storm,” Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, November 2014, http://www.operationghettostorm.org/uploads/1/9/1/1/19110795/new_all_14_11_04.pdf.[↩]

- Anderson, “Read Remarks.”[↩]

- Jenelle Taylor, “Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed Conducts Meeting With ‘Black Lives Matter’ Leaders,” Vibe, July 12, 2016, https://www.vibe.com/2016/07/mayor-kasim-reed-meets-with-black-lives-matter-leaders.[↩]

- Taylor, “Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed Conducts Meeting With ‘Black Lives Matter’ Leaders.”[↩]

- Sarah Abdelaziz, “Ratcheting a Way Out of the Respectable: Genealogical Interventions into Atlanta’s Respectability Politics,” Master’s Thesis, Georgia State University, 2017, https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/wsi_theses/64.[↩]

- Emma Hurt, “Keisha Lance Bottoms, A Possible Biden VP Pick, Sees Profile Rise Amid Crises,” NPR, July 10, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/07/10/889500483/keisha-lance-bottoms-a-possible-biden-vp-pick-sees-profile-rise-amid-crises.[↩]

- Hobson, Black Mecca.[↩]

- Devyn Springer, “Killer Mike and T.I. sold out in Atlanta. Let’s talk about why they did it,” Independent, June 2, 2020, https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/killer-mike-atlanta-speech-ti-video-george-floyd-a9543551.html.[↩]

- Ryan Young and Devon M Sayers, “Woman Charged in Atlanta Wendy’s Arson given $10,000 Bond in First Court Hearing,” CNN (Cable News Network), June 24, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/23/us/natalie-white-wendys-arson/index.html.[↩]

- Thomas Wheatley, “23 Days: Stories from the Occupation of the Wendy’s Where Rayshard Brooks Was Killed,” Atlanta Magazine, August 7, 2020, https://www.atlantamagazine.com/great-reads/23-days-stories-from-the-occupation-of-the-wendys-where-rayshard-brooks-was-killed/.[↩]

- Wheatley, “23 Days: Stories from the Occupation.”[↩]

- Shaddi Abusaid, “Atlanta Protest Organizer among 2 More Arrested in Arson at Wendy’s,” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 2, 2020, https://www.ajc.com/news/crime–law/breaking-atlanta-protest-organizer-among-arrested-wendy-arson/KJ8RY01nrtYBdfIOI3NApJ/.[↩]

- “Atlanta Authorities Pursue Wendy’s Arson Suspects,” CBS Atlanta, June 17, 2020, https://atlanta.cbslocal.com/2020/06/17/rayshard-brooks-atlanta-authorities-pursue-wendys-arson-suspects-1/.[↩]

- Ryan Young and Devon M Sayers, “Woman Charged in Atlanta Wendy’s Arson given $10,000 Bond in First Court Hearing,” CNN, June 24, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/23/us/natalie-white-wendys-arson/index.html.[↩]

- Collin Kelley, “Mayor, police chief denounce ‘anarchists’ and ‘terrorists’ who destroyed city; curfew begins at 9 pm,” Atlanta Intown Paper, May 30, 2020, https://atlantaintownpaper.com/2020/05/mayor-police-chief-denounce-anarchists-and-terrorists-who-destroyed-city-curfew-begins-at-9-p-m/.[↩]

- Brakkton Booker, “Rayshard Brooks’ Funeral Held at Church Where Martin Luther King Jr, Preached,” NPR, June 23, 2020, https://www.npr.org/sections/live-updates-protests-for-racial-justice/2020/06/23/882053318/rayshard-brooks-funeral-to-take-place-at-martin-luther-king-jr-s-church.[↩]

- Young and Sayers, “Woman Charged in Atlanta Wendy’s Arson given $10,000 Bond in First Court Hearing.”[↩]

- Mea Watkins and Tim Kephart, “Fewer than 13% of Protestors arrested in Atlanta were out of towners,” CBS 46, June 3, 2020, https://www.cbs46.com/news/fewer-than-13-of-protesters-arrested-in-atlanta-were-out-of-towners/article_9aca528a-a5c2-11ea-9642-335199544b78.html.[↩]

- Joshua Sharpe, “As court dates loom, many arrested during Atlanta summer protests want charges dropped,” The Atlanta Journal Constitution, October 27, 2020, https://www.ajc.com/news/crime/as-court-dates-loom-many-arrested-during-atlanta-summer-protests-want-charges-dropped/NEH5OGCF7VGIJLNGHZWRZFKFAM/.[↩]

- WSBTV News Staff, “No more curfew in place for city of Atlanta Sunday,” WSB-TV, June 7, 2020, https://www.wsbtv.com/news/local/atlanta/no-more-curfew-place-city-atlanta-sunday/H5XPCZNUVJHSTIRKDWCXDBN7QI/.[↩]

- Atlanta Anti-Repression Committee, March 16, 2021, https://aarc.substack.com/[↩]

- Kruse, White Flight.[↩]

- Matt Kempner, “Andrew Young: Atlanta police face ‘unlovable little brats some times’”, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 12, 2016, https://www.ajc.com/news/local/andrew-young-atlanta-police-face-unlovable-little-brats-some-times/f7mIVNMsNpuNBjv2hjOK7K/.[↩]