The day will come when the people will come from across the ocean to see the wonders of Dekalb County in her granite mountains.1

“What used to be here?” is an ever relevant question when one lives in a city like Atlanta that’s regularly dilating and contracting between development and preservation.

In Atlanta big urban renewal projects such as MARTA, the 1996 Olympics, and more recently the construction of Mercedes Benz Stadium, and the ongoing multi-million dollar Atlanta BeltLine project have been pitched regularly every generation for the last century, repeatedly shaking up not only the architectural and natural landscapes of Metro Atlanta but also forever shifting the socio-politico-economic structure of the area. There used to be a rather poetic “answer” to the question “what used to be here?” on a sign in someone’s front yard in East Atlanta on Moreland Avenue that read “This Used To Be a Forest.” While Atlanta has often been dubbed a “city in a forest,” I often find myself instead saying “This Used To Be a Mountain” whenever I see copious amounts of Stone Mountain’s signature granite as I drive through Atlanta’s major streets and neighborhoods.

Working on I Am The Mountain over the past few years I’ve often wondered what all of the granite all over the city and surrounding towns means, so I am grateful to collaborate with Atlanta Studies and ATLMaps and its contributors to ambitiously endeavor to map and try to understand the many possible meanings and implications of the undeniable pattern of granite running through Metro Atlanta.

If Atlanta were a poem, then ATLMaps offers a way to explicate Atlanta’s infinite layers. This particular layer reminds me of when I would turn over big stones in my yard as a child and study the roly-polies and earthworms living beneath them. Each structure pinned to this ATLMaps layer, or neighborhood with a high concentration of the trademark granite, can figuratively be lifted up to reveal unexpected living history which may help explain why this stone was intentionally used so widely throughout the city’s infrastructure (so much so that practically every curb could well be mapped if the scope of this map were not limited to significant structures and neighborhoods, many of which have grand entrances or “gates” made of the granite).Ultimately, I believe mapping the abundant locations featuring granite quarried from Stone Mountain has potential to shed light on questions about what gets preserved and repurposed whene the city experiences another round of urban renewal. This might even lead us to ask questions, like: why is it that some buildings and entire town districts featuring the granite are listed in the historic register, while other structures and locations featuring the same stone are not accorded the same historic status or respect? For example, some of the granite walls lining streets like Moreland Avenue are crumbling in places, while others in East Lake were bulldozed altogether by developers, and some of the big granite walls along North Avenue have been tagged with graffiti or painted over with murals, some of them through Living Walls or the Atlanta BeltLine.

Early on, it almost seemed plausible that, if mapped, the granite structures and site walls might well follow the very railway tracks of the Atlanta BeltLine. The granite was transported along various rail lines connecting the quarries with Atlanta via the Georgia Railroad and the Atlanta, Stone Mountain, and Lithonia Railway (as well as various new railways frequently being chartered at this time, such as the Stone Mountain Granite Railway, the Georgia Granite Railroad, the Atlanta Belt Railway Company) – though not always without incident or on time due to a number of factors, among them, but not limited to, striking stone-cutters, railcar shortages, and fluctuating freight costs.2 As I began plotting the locations and doing further research, though, I quickly gleaned that the number of sites made of the granite far exceeds the boundaries of the proposed BeltLine. That said, Stone Mountain granite is indeed prevalent along many sections of the Atlanta BeltLine, particularly at points, though not exclusively, where the Georgia Railroad once crossed at bridges solidly buttressed by the granite, such as at North Avenue and Ralph McGill Blvd. along the Eastside Trail.

Stone Mountain Granite: A Confederate Brand?

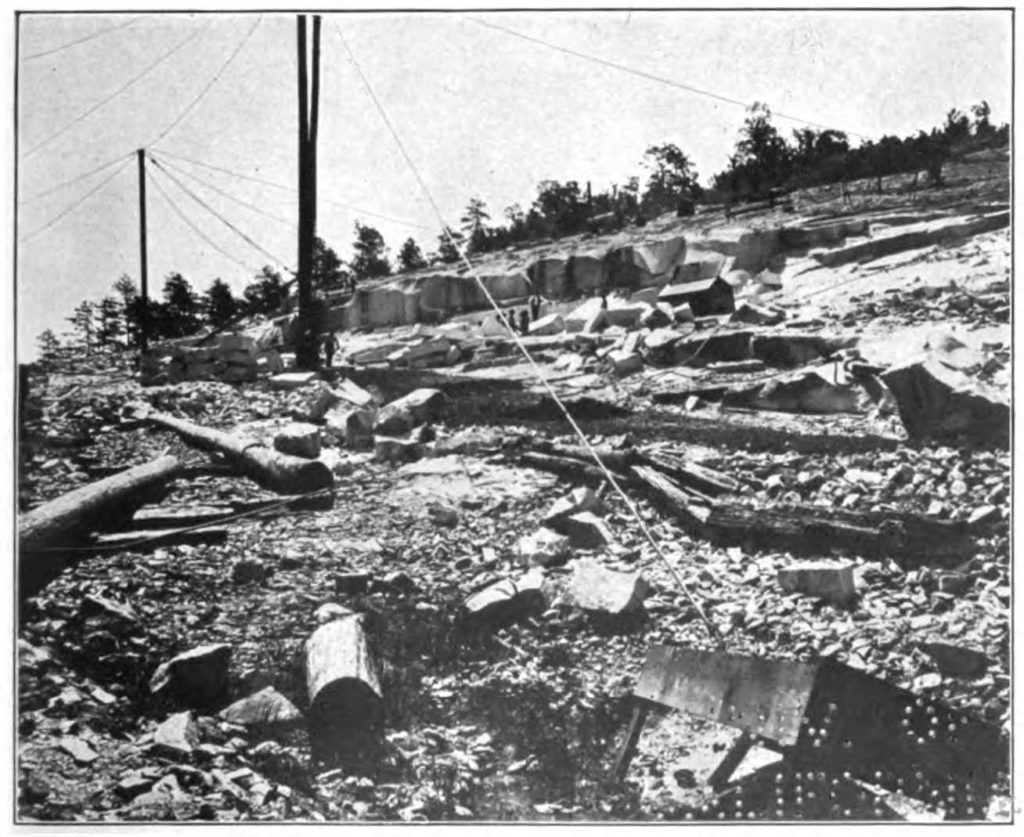

Stone Mountain granite isn’t prevalent throughout the city just because it was once in such plentiful supply in the area. And its presence all over doesn’t just boil down to a romantic explanation of how a mountain served as a host for Atlanta, the way legends tell of cities like ancient Mesopotamia developing around rivers full of resources to support a civilization. A good place to begin a preliminary analysis of where and why the granite from Stone Mountain ended up where it did is the July 1887 sale of Stone Mountain to the Venable Brothers for $40,000 and the trade of Big Ledge, another quarry site at Arabia Mountain in Lithonia (now a National Heritage Area), to the Davidson Granite Company.3 Closer examination of this ATLMaps layer, especially as it continues to get filled in over time, could at some point elucidate the interpersonal and business dealings among many of the local granite barons, real estate developers, contractors, city planners, and politicians of Atlanta at the time of the granite industry’s peak. It will likely also show that many were former Confederate soldiers or Lost Cause sympathizers who comprised a well-off fraternity that stood to profit the most from the success of the granite and real estate industries. Meanwhile the back-breaking labor fell to countless, nameless granite workers, stone cutters, and convict labor – and before that the enslaved laborers – who built so much of the city, particularly its streets of brick and granite, during the Reconstruction Era and throughout the Jim Crow years leading up to the Civil Rights Movement.4

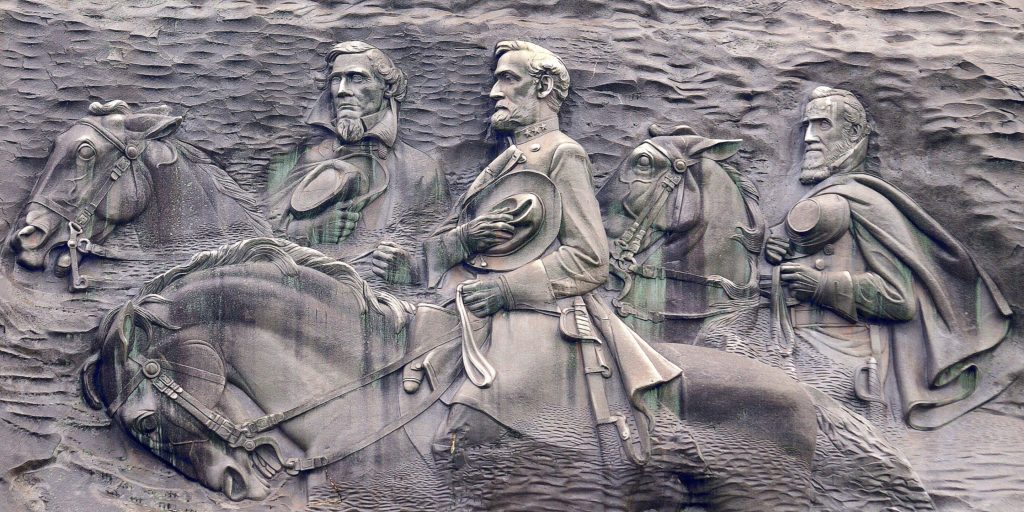

Pressure was high around the turn of the twentieth century to use “Georgia stone” and Georgia resources and materials5 (“shop local” is hardly a new concept). way that granite outfits like the Stone Mountain Granite Company pushed their durable stone back then (when the Venables were not often outright strategically donating their granite for free to secure contracts, such as when they offered to provide the granite for Atlanta’s Masonic Temple6) was to boast that it was “fireproof,” a selling point in a city mythologically reborn as a phoenix from the embers of Sherman’s 1864 inferno and that continued experiencing a motherlode of structure fires before and after Atlanta’s Great Fire of 1917. It was also a time of great urgency in proving the superiority of Georgia’s granite against other stones nationwide (possibly to the point of overcompensating by using it everywhere), so as to secure as many city and federal government contracts as possible. Around 1895, Georgia granite had been deemed to have inferior resistance strength by the District of Columbia and was therefore cut out of bidding for such government projects until the ban was lifted in 1916 – because the granite had proven itself.7The presence of this granite is so familiar that it even presents at times as its own recognizable “brand.” A brand of just what, though? Because of the Confederate carving on Stone Mountain and Stone Mountain Park’s enduring Confederate “brand” (opening its gates on the centennial of Lincoln’s assassination as a slap in the face to the Civil Rights Movement), has the granite in Metro Atlanta beyond the mountain proper ever resonated with a type of Confederate brand recognition? I think it is fair to suggest that it does and that the granite originating from the mountain, especially when the mountain was monopolized by the Venables and the Ku Klux Klan, more than likely contributed to institutionalized racism then and now, however nuanced, through its frequent use in Metro Atlanta’s architecture and infrastructure. It’s as if the rock used in neighborhoods throughout Atlanta represented a stealthy extension of the white supremacy emanating from the Klan and Confederate stronghold at Stone Mountain.The mountain itself will always be an innocent gift of nature, home today to a variety of plants and animals and a favorite place to hike for quite a cross-section of people. But it’s simply impossible to ignore how, along with the mountain’s continued commodification and Disneyfication,8 it was forever politicized by the Klan’s declaration of their twentieth century rebirth there over Thanksgiving weekend in 1915 and by their continued use of the mountain for gatherings for decades thereafter. The Venables deeding the north face of Stone Mountain to the United Daughters of the Confederacy to turn into the Confederate carving that took over fifty years to complete further debased the mountain. The carving was perfunctorily completed in 1972 and still rises over Atlanta in 2017 as a painful relic of white supremacy. A few years in advance of the 1996 Summer Olympics, thirteen Confederate flags on top of the mountain were removed, around the same time the decades-long tradition of Klan rallies in Stone Mountain Village ceased. It has always been my opinion that Stone Mountain Park bears a special responsibility, perhaps even above many other Confederate monuments, to never perpetuate the kind of white supremacy it accommodated and instigated during the Klan’s reign there and during the Civil Rights Movement when the park was created as a direct affront to integration (the same arguments about white culture and southern heritage being threatened that get trotted out now by white nationalists were used in 1965, too).

I grew up five minutes away from Stone Mountain Park in a middle-class neighborhood along the railroad tracks on E. Ponce de Leon Avenue during a time when Klan rallies still took place in a field beside the mountain (the street in Shermantown is still named Venable Street, and former Imperial Wizard James Venable died my senior year in high school in 1993).9 Americans have been increasingly confronting and coming to terms with the true white supremacist meaning of Confederate monuments, flags, and symbols which often serve as beacons of racist violence, and many of these outmoded monuments and statues are rightfully being removed from their pedestals in America’s town squares and being relocated to more appropriate spaces such as cemeteries and museums.

Conclusion

As this map layer is already beginning to illustrate, Stone Mountain granite literally helped to build Atlanta. Since a great deal of Atlanta is structurally linked with Stone Mountain, Atlanta is arguably implicated, however symbolically, in whatever has gone on there and goes on there right now, and should care more than ever what will happen there next. How a city uses land and natural resources and labor will always be of great importance. Atlanta used Stone Mountain granite to build and conceive of its infrastructure, house its citizens and workers, and to create and maintain shared public spaces in between. As the city and region continue to make decisions about future development and the fate of historic structures and Stone Mountain itself, it’s important to keep the granite’s continuing presence and its context in mind.

Citation: Byrne, Shannon. “This Used To Be A Mountain: Mapping Stone Mountain Granite in Metro Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. October 17, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20171017.

A native of Stone Mountain, GA, Shannon Byrne runs I Am The Mountain, a website that explores Stone Mountain from a wide variety of perspectives.

Notes

- Sarge Plunkett, “Wonder of World in Granite,” Atlanta Constitution, Feb. 13, 1898.[↩]

- “Our Neighbors, The Allies of Atlanta in Her Onward March, Sketches of Towns Tributary to the Gate City, and Last Year’s Business of Each, Atlanta Constitution, September 11, 1875; “Chipped Stone 150 Cars Strong Tendered Free,” Atlanta Constitution, May 27, 1899; “Notice” (Atlanta Belt Railway Company charter applied for), Atlanta Constitution, September 8, 1899; “The Jubilant Asphalt Trust As It Strikes The People of Atlanta: A Statement of Facts as Presented by W. H. Venable, Explains Why He No Longer Fights To Secure the Contract on Capitol Avenue–Why He Requested Chance to Compete Again,” Atlanta Constitution, April 1, 1901; “Will Build Road To Quarry: Capitalists To Build from Rock Chapel Mountain to Lithonia, Dekalb County,” Atlanta Constitution, February 14, 1904; “Railroad Must Move Granite: Commissioner Stevens Investigates Conditions at Lithonia,” Atlanta Constitution, April 13, 1907; “Granite Men Get Demurrage: Commission Approves the Claims on Account of Tie-up at Lithonia,” Atlanta Constitution, May 4, 1907; “Paving Concerns Seek Injunction: Road Material Companies File Petition Claiming Violation of Charter by Georgia Railway and Power Co.,” Atlanta Constitution, June 30, 1916; “Georgia Granite Railroad To Be Sold At Auction in Decatur in December,” Atlanta Constitution, November 19, 1917; “Sewage System Delays Will Be Rigidly Probed,” Atlanta Constitution, February 12, 1913; “Belt Line Contract Is Let,” Atlanta Constitution, October 21, 1899.[↩]

- “There Has Been A Change: Southern Granite Company Changes Hands–Stone Mountain Still Stands,” Atlanta Constitution; July 18, 1887; “Venable’s Big Rally: At the Courthouse Last Night A Big Crowd,” Atlanta Constitution; October 1, 1890; Big Granite Deal: The Venable Brothers Secure A Monopoly of the Stone Mountain Quarries,” Atlanta Constitution, March 14, 1894.[↩]

- Mimi Kirk, “Forced Laborers Built Atlanta’s Streets. How Should the City Remember Them?” CityLab, Mar 31, 2017, https://www.citylab.com/life/2017/03/the-quest-to-memorialize-forced-black-labor-in-atlanta/521499/; Richard Becherer, “Bricks and Bones: Discovering Atlanta’s Forgotten Spaces of Neo-Slavery,” 2012, Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Annual Meeting Proceedings, 436–44.[↩]

- “A Very Plain Answer,” Atlanta Constitution, November, 25, 1883. “Stone Mountain Granite: Beautiful Specimen of The Georgia Granite Taken From 25 Feet Below the Surface,” Atlanta Constitution, November 25, 1883.[↩]

- “The Masonic Temple: Generous Offer of Hon. W. H. Venabale, Stone Mountain Granite Free of Cost, Except the Mere Expense of Quarrying if the Building is a First Class One,” Atlanta Constitution, August 1, 1890.[↩]

- “Fighting Georgia Granite,” Atlanta Constitution, January 26, 1895; “A Final Rejection: Georgia Granite Has Been Shut Out By the Government, No Power to Investigate The Matter,” Atlanta Constitution; February 20, 1895; “For Georgia Granite Howard Makes Fight: Congressman Alleges Stone Mountain Company Is Victim of Discrimination,” Atlanta Constitution; July 31, 1913; “Ban Has Been Lifted on Georgia Granite,” Atlanta Constitution, April 22, 1916; “Big Government Order For Georgia Granite: $85,000 Worth of Stone Mountain Rock Will Be Used For Marine Barracks,” Atlanta Constitution; May 4, 1916; “Millions of Tons Of Finest Granite Lie Close to Atlanta,” Atlanta Constitution, September 26, 1917.[↩]

- Tim Moore, “The Disneyfication of Stone Mountain: A Park’s Response to its Visitors,” Honors Thesis, American University, 2010, http://auislandora.wrlc.org/islandora/object/0910capstones%3A88/datastream/PDF/view.[↩]

- “300 Klansmen Gather for Rally, Burn Crosses Without Incidents,” Atlanta Constitution; September 2, 1979; “I Remember Hour” The DeKalb History Center, James Venable, August 28, 1982 (recorded on anniversary of MLK, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech), James Mackay, Interviewer, http://www.dekalbhistory.org/documents/2012.3.3JVenable5231982.pdf[↩]