The recent passing of U. S. Representative John Lewis generated many tributes to his legendary life and career.

Lewis achieved prominence early in life as one of the most visible leaders of the Southern civil rights movement. He was one of the key organizers of the 1963 March on Washington. During the 1965 “Bloody Sunday” march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama State Troopers fractured his skull as he led protesters across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. After the height of the movement in the mid-1960s, Lewis spent the next two decades continuing his civil rights organizing and beginning to work in government posts, including a stint on the Atlanta City Council. In 1986, he won a seat in the U. S. House of Representatives, which he held until his death. He spent his long career in the House drawing on his broad interpretation of the legacies of the civil rights movement, which for him meant supporting civil liberties and privacy rights in the face of government surveillance, supporting national health insurance, and advocating for LGBT rights.

However, one of the less remembered episodes of his career, the 1987 Mariel Cuban uprising in Atlanta’s federal penitentiary, deserves further consideration in our current moment, especially given Atlanta’s burgeoning status as a destination for immigrants desiring opportunity and a new home. It also deserves to be told as an important story in Lewis’s own career. After the height of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, many its leaders continued to advocate not only for the rights of African Americans but also those of other traditionally marginalized groups, such as immigrants. For his part, Lewis urged compassion for the Cubans imprisoned in Atlanta, extending the broad legacies of the civil rights movement into a new era.

In October 1980, Cuban president Fidel Castro allowed any Cuban who wanted to leave the island to do so. Thousands of Cubans accepted the offer, with around 125,000 fleeing the island for the nearby shores of Florida. Most of the immigrants settled in Miami, and many eventually gained U. S. citizenship. On the whole, in the context of Ronald Reagan’s Cold War anti-communism, these Cuban migrants received much more American support than other Caribbean migrants fleeing persecution, such as those trying to escape Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier’s Haiti around the same time.1

However, some of the migrants included Cubans who had been incarcerated in Cuban prisons, Others broke American laws after reaching the U. S. These two groups of “excludables” were imprisoned at sites such as the Atlanta federal penitentiary, as well as a penitentiary in Louisiana. The Atlanta penitentiary had achieved national fame decades earlier for holding socialist leader Eugene Debs as well as the Russian anarchist Alexander Berkman, both imprisoned for anti-war activities conducted during World War I. It was notable that some of these immigrants had been incarcerated in Cuban prisons for anti-Castro activities, which they thought would earn them acclaim in the United States. However, they were treated just the same as any other supposed “criminal,” locked up in American prisons and jails upon arrival. And once they had admitted to serving time in Cuban prisons, they could not recant this admission. It was a baffling and short-sighted decision, but one implemented nonetheless in the misguided name of community security.2

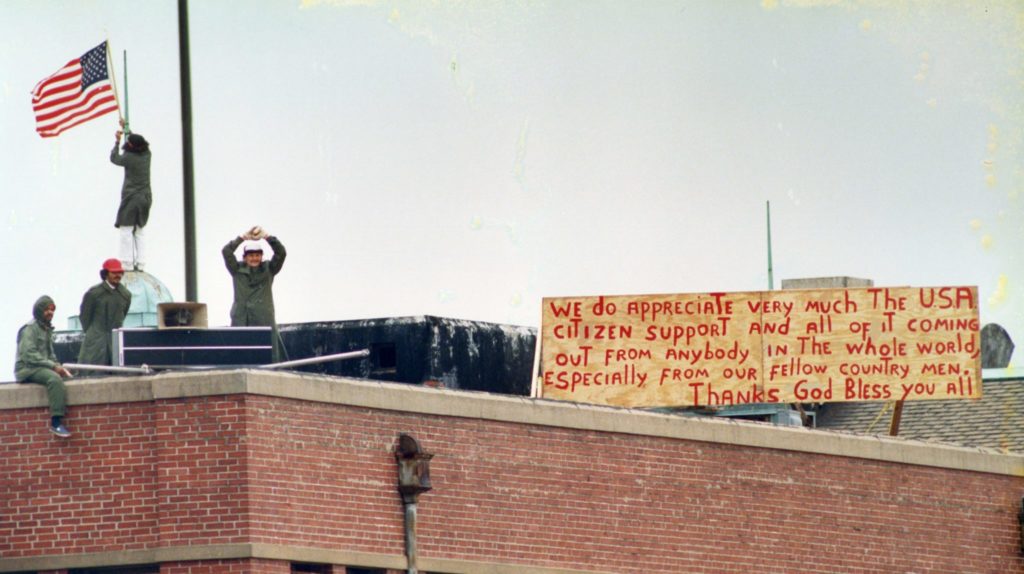

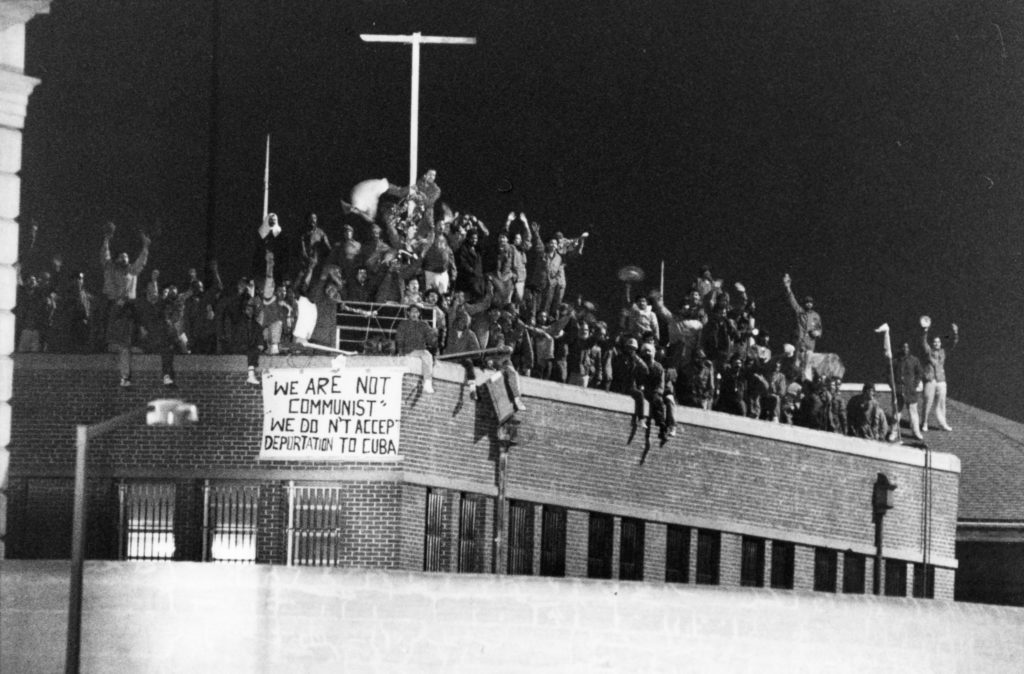

The “excludables” remained in legal limbo for several years, with American authorities unsure of what to do with them. The U. S. and Cuba agreed in 1984 on the return of most of these prisoners to Cuba, but the accord fell through due to ongoing diplomatic difficulties between the two nations. However, Cuba and the U. S. restarted the agreement in November 1987 after further negotiations, and deportation seemed imminent. The Cuban prisoners held in Atlanta, who did not want to return to Castro’s Cuba, took control of the prison and captured over 100 hostages. After eleven days, the Cubans agreed to surrender in exchange for a lengthier review process. One person died during the standoff, a Cuban prisoner killed by a corrections officer. In the end, owing to ongoing tension between the United States and Cuba, most of the prisoners received community release in the U. S. and never returned to their home country.3

Georgia’s representatives in the U. S. Congress had divergent views on the prison uprising. Republican Pat Swindall, whose district was based in DeKalb County, argued that the prisoners in Atlanta should not be allowed to enter the general U. S. population, as they represented a threat to public safety and order. He warned his constituents that, if released, these prisoners might end up on the streets of DeKalb, with potentially perilous consequences for the county’s citizens. However, Lewis argued that the prisoners had undergone extreme stress while incarcerated, leading to the desperate uprising, and that they should be treated with compassion and humanity. He claimed that, given proper support, they could enter American communities and make new lives for themselves. Swindall and Lewis engaged in a sustained public debate through statements in newspapers as well as debates on radio programs, with each arguing vociferously for his side of the issue.4

A clip from C-SPAN’s February 4, 1988, broadcast of the hearings of the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Courts, Civil Liberties and the Administration of Justice, concerning the two November 1987 Mariel Cuban prison uprisings in Atlanta, Georgia, and Oakdale, Louisiana. This clip focuses on Lewis’s testimony in regard to the uprising in Atlanta.

In the end, Lewis’s position won out, since the Cubans were allowed to remain in the United States, but this was due more to the ongoing diplomatic difficulties between the U. S. and Cuba and less to his individual efforts.

Nonetheless, the episode deserves mention during summaries of Lewis’s career as another clear example in which he urged compassion and understanding for marginalized and helpless groups of people. Highlighting the importance of the incident is especially significant given the explosion of immigrant communities on Buford Highway, and the emergence of Clarkston as a refuge for migrants fleeing Somalia, Ethiopia, Syria, and other areas of conflict. Lewis seemed to view the recognition of the essential humanity and dignity of immigrants seeking safety and opportunity as part and parcel of the same set of concerns that motivated his advocacy for African American equality in the civil rights era and beyond. And, in turn, concerns for immigrants and refugees have become an essential and enduring part of Atlanta’s broader cultural identity. Issues of incarceration have become a special source of concern. For example, in 2018, Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms signed an executive order disallowing the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency from housing its detainees in the Atlanta City Detention Center, after popular outcry against the agency’s methods.

When I presented material on this subject in February 2019 at the annual Southern Studies Conference in Montgomery, Alabama, one of the audience members identified herself during the question-and-answer period as a metro Atlanta native. Although she had taken courses on Georgia history during middle school and high school, she said that she had never heard of this episode before. Given the importance of Atlanta’s identity as a welcoming destination for immigrants and refugees, as well as growing scholarly and popular interest in our nation’s systems of incarceration and punishment, she argued that the incident should be mentioned in courses on Georgia history in the future as a way to bridge these two trenchant and timely themes. I agreed with her.

Citation: Camp, Michael. “John Lewis’s Forgotten Fight: The Mariel Cubans in Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. January 29, 2021. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls01292021.

Michael Camp received a Ph.D. in History from Emory University in 2017. His book Unnatural Resources: Energy and Environmental Politics in Appalachia after the 1973 Oil Embargo appeared in the University of Pittsburgh Press’s History of the Urban Environment Series in 2019. Email him at wcamp444@gmail.com.

Notes

- See, for example, Alejandro Portes, David Kyle, and William W. Eaton, “Mental Illness and Help-seeking Behavior Among Mariel Cuban and Haitian Refugees in South Florida,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 33(4): pp. 283-298.[↩]

- The best book-length treatment of the Mariel Cubans’ arrival in the United States and the subsequent prison uprisings remains Mark S. Hamm, The Abandoned Ones: The Imprisonment and Uprising of the Mariel Boat People (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1995).[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- See, for example, “Reps. Swindall, Lewis clash, once again, on the handling of Cubans,” Atlanta-Constitution, November 24, 1987, p. 4A.[↩]