Students, family, and friends often ask me, “What makes you love Georgia State University so much?”

Since 1987, my answer remains the same, “The people I have met along this journey.” Jacqueline Anne Rouse, Ph.D., was one of those people. I formally met Dr. Rouse in 2005 when I entered the history department’s master’s program. Dr. Akinyele K. Umoja, an undergraduate professor and self-appointed mentor, encouraged me to enter graduate school and insisted that I meet Dr. Rouse.

Now, every cultivated student knows that before you introduce yourself to a professor, you research him or her, which is what I did. I discovered that Jacqueline Anne Rouse was a native of Virginia. She earned a bachelor’s in Afro-American history from Howard University, a master’s in African American history from Atlanta University, and a doctorate in American Studies from Emory University. She taught at junior colleges, state universities, and Historically Black Colleges and Universities, including Georgia Institute of Technology, Jackson State University, and Morehouse College. She interned at the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, held fellowships with the Carter G. Woodson Association for the Study of African American Life and History in Washington, D.C., Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, and the Interdenominational Theological Center in Atlanta, plus worked with academic legends Alton Hornsby, Jr., and Dorothy Cowser Yancy. She published works on Margaret Murray Washington, Lugenia Burns Hope, and Septima Poinsette Clark, and was a co-editor of Women in the Civil Rights Movement: Trailblazers and Torchbearers, 1941-1965, a staple in American literature. Rouse served and held leadership positions with numerous organizations, including the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, the Association of Black Women Historians, the Southern Historical Association, and the Southern Association for Women Historians. I learned that she came to GSU in 1991 and taught various courses in the history department and much more. I felt astonished and a bit ashamed that I had never heard of this scholar. However, I now understood why Dr. Umoja demanded that I meet her. (What a life-changing event that became.)

I walked to the history department, was guided to her office, and knocked on the partially closed door. “Yes, you may enter,” a soft Southern voice said. “Hello, are you Dr. Jacqueline Anne Rouse?” I asked. “Who else would be sitting in my chair, in my office,” was the reply. That statement began the student-professor, mentee-mentor, and friend-confidant relationship that I am reflecting on today.

As a new, non-traditional graduate student I already felt out of place. Now, this woman who looked like me responded in this manner. (Dr. Umoja, who did you send me to?) I entered and waited to be told that I may have a seat. She asked who I was, why did I come to her, and said that I looked familiar. I reminded her that we met and spoke briefly in a campus parking lot a few months earlier. (Although Dr. Rouse may forget a name, she remembered a face.) She drilled me on personal and academic goals for what seemed to be an hour and then asked if I wanted to go to lunch. Our relationship began.

For the next seven years, Dr. Rouse served first, on my thesis committee, then on my dissertation committee. I took every class that she taught and tried to get her to provide me with directed readings for others. She taught me how to deal with difficult faculty and introduced me to faculty with similar research interests. She spoke with her colleagues on my behalf, and suggested my path after completing my master’s, “You’re a good student. You have a 4.0 g.p.a. You will get a doctorate.” When I completed the doctoral application, I was awarded a graduate teaching assistantship. I know that Rouse had everything to do with this. (Dr. Umoja, thank you.) During the doctoral process, students learn how to teach a university course. Although many professors taught me how to create syllabi, grading rubrics, choose course texts and content, Rouse taught me how to teach students. “Learn something about each one of them. You know who they are looking at, but you don’t know who is looking back at you,” she would say. She was the epitome of a mentor.

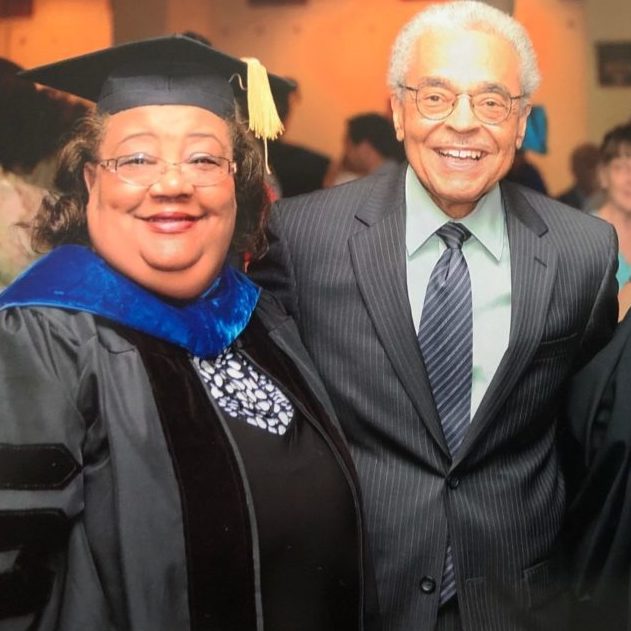

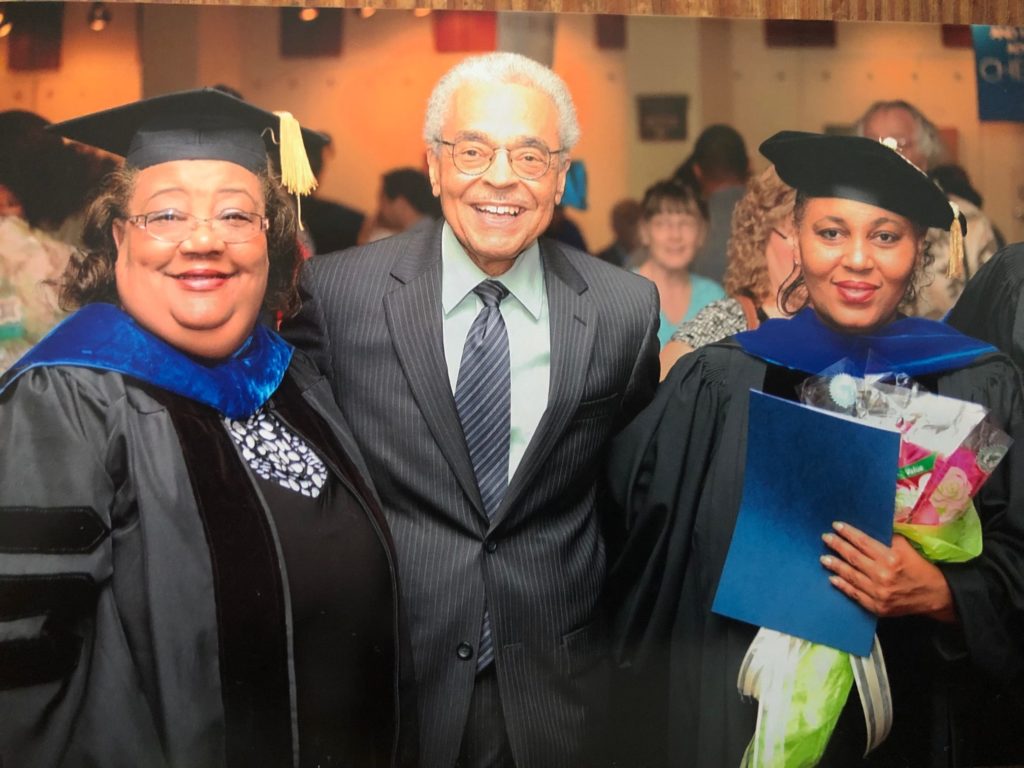

When I earned a doctorate in 2014, Rouse was there. I was conflicted whether my committee chair, Clifford M. Kuhn, or Rouse should hood me. Rouse must have sensed my inner struggle because before I could ask her opinion she said, “Cliff will hood you, but I will be there to hood Derrick.” She rode with my family to and from the ceremony and attended my surprise party afterward. (By now, my role as her chauffeur was solidified.) I often wondered how our relationship would be after I completed my degrees. It seems that that relationship is the one that I love the most.

Rouse did not stop her mentorship once her students earned their degree. She wanted all of her students to gain employment into the Academy, “Some of you all will go to HBCUs. Some of you all will go to state schools, but all of you will go somewhere.” And that is what she helped each of us do. The Rouse umbrella is large and covers a lot of territories. For personal reasons, I wanted to remain at Georgia State. Rouse emphatically told me, “You will. Something will open or a position will get created.” In 2019, a lecturer position “was created” in the Department of African American Studies. I applied, interviewed, and received the position.

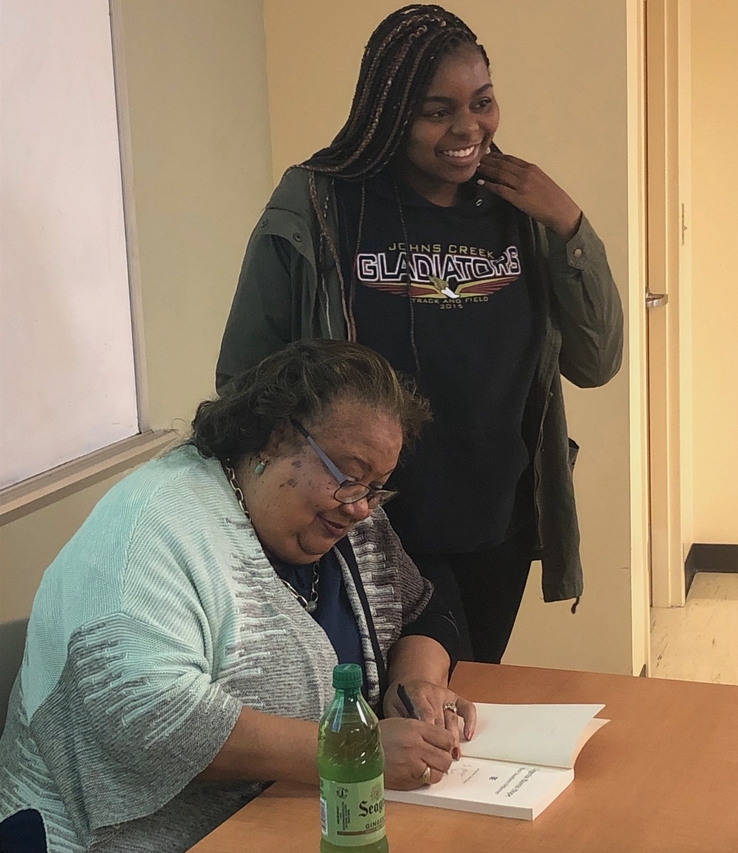

As lecturer, I get the privilege to teach many courses. My favorites are the ones that Dr. Rouse created. In 1991, she created, AAS1140 – Introduction to African American History and Culture, GSU’s first course on African Americans. Since State was on the quarter system then, the entire trajectory of people of African American descent was told in nine weeks. Rouse said that the course was meant to start a discussion of the African American contribution to the United States, not to tell the whole story. Rouse was glad to learn that this course was split into two in 2019, AAS1141- African American History I (to 1865) and AAS1142 African American History II (1865 – present). Although she loved history, her specialty was African American women. Therefore, in 1994 she created her second course AAS4660 – African American Women. When I teach these courses, my lecture begins with a discussion on Jacqueline Anne Rouse. She guest lectured for me numerous times and signed her “baby” Lugenia Burns Hope: Black Southern Reformer for my students.

Rouse and I often attended church together, attended funerals together, and protested global, national, and local injustices together. We spoke two or three times per week. If she did not answer after three days, I accidentally on purpose dropped by her home. (After dropping by two times, she started answering when I called.) When I could not take her to an appointment, I knew that Paula Sorrell (history department business manager), Dr. Charmaine Paterson (student), Dr. Barry Lee (student), or one of her church friends had the honor. Our families know each other. She was with her loved ones, her biological family when she departed this earthly life. My life was forever changed for the good when I met Dr. Rouse. Dr. Umoja, I thank you for the introduction. Mostly, I thank our Creator for the of spirit of Dr. Jacqueline Anne Rouse.

Lisa R. Shannon was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and reared in Tampa, Florida. After attending the University of Southern California and the University of Florida, she earned a B.A. in African American Studies, a M.A. in history, and a Ph.D. in history, each from Georgia State University. Shannon is a his/herstorian whose work focuses on community relations, grassroots activism, and Southern Americanculture. Her forthcoming publication, “Creating Community: A History of The East Washington Community in East Point, Georgia,” explores the inception, evolution, and survival techniques of one of Georgia’s most resilient African-American communities. A mother of two Georgia State University alumni, Shannon believes that her mission is to teach, “The community that we serve is broad, very diverse, and non-discriminatory. It pleases me to see students grow academically, socially, and culturally.”