Alton Hornsby’s passing last year should be an occasion to reflect on the loss of a generation of African American intellectuals who learned, researched, and wrote against the backdrop of the Civil Rights and Black Power eras.

Vincent Harding (2014), Hornsby, and most recently Lerone Bennett (2018), among so many other African American scholars, helped readers figure out what it meant to be African American during and after the Civil Rights Movement. In the contemporary moment, as African Americans once again prove to be pivotal to the nation’s future in a historical election, it’s worth taking the time to consider how Alton Hornsby gave African Americans agency in both southern history and the southern present.

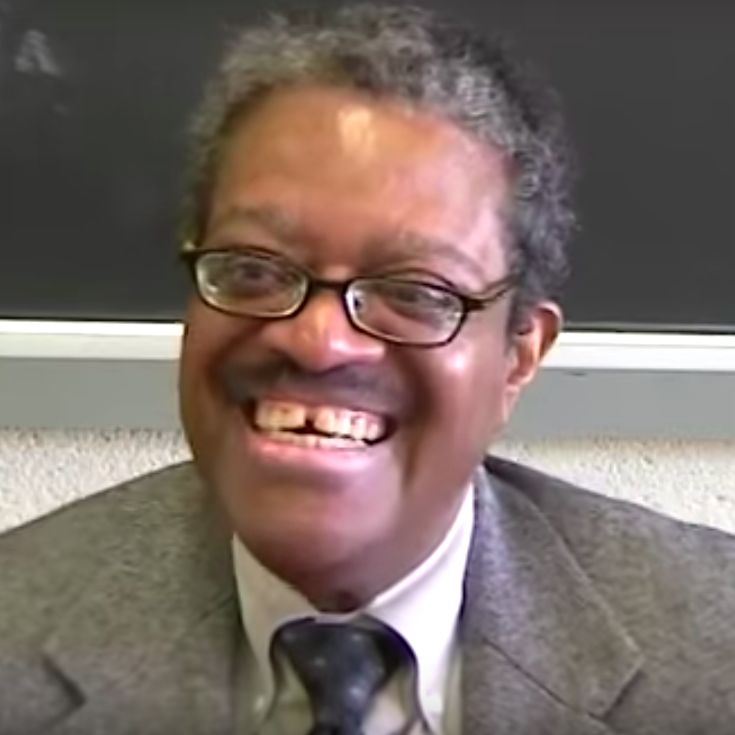

What makes Hornsby’s death particularly tragic for those of us whose research centers on Atlanta was his unique tie to the city, both through his writing and teaching. A native of Atlanta, Hornsby received his BA from Morehouse College in 1961 while participating in the Atlanta-based movement for equal rights (Hornsby discussed his involvement in the Atlanta Student Movement in the 2016 oral history interview to the right). In 1969, Hornsby would become the first African American to receive a Ph.D. in history from the University of Texas at Austin.1 And after a brief teaching stint at Tuskegee University, he would return to his hometown and alma mater to teach at Morehouse, where he eventually became Chair of the History Department and the Fuller E. Callaway Professor of History. Throughout his career at Morehouse, Hornsby was a fixture in Atlanta’s intellectual scene and in the vibrant national discourse among African American scholars that emerged after the Civil Rights Movement. He served as editor for the Journal of African American History, the scholarly journal of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, for twenty-five years – a lengthy tenure second only to that of its founder, Carter G. Woodson. During his time there, he published numerous historians who applied an ever more nuanced understanding of slavery, Reconstruction, and the Civil Rights Movement, just as all three of those fields were transformed by new paradigms of thinking which centered African American agency.

Learn About Dr. Hornsby’s Participation in the Atlanta Student Movement in The Oral History Below

In his own scholarship, Hornsby applied a laser focus on the centrality of Atlanta’s vibrant black political life to the entire South. His book, A Short History of Black Atlanta, 1847–1993 (2003), remains unique in its comprehensiveness as a study African American life in a southern city. The book’s example of an on-the-ground study of African American metropolitan life is still needed for far too many other American cities. Hornsby’s later work, Black Power in Dixie: A Political History of African Americans in Atlanta (2016) is arguably the standard by which any other work about African American political life in Atlanta will be measured. Its deep analysis of Atlanta’s black politics is virtually unmatched in any other single volume history – going from the antebellum period until the late twentieth century, and linking black political power across time periods. It is hard to imagine the work of, for example, Maurice Hobson, touching on the growth of a “Black New South,” without thinking about how Hobson responds to Hornsby’s examination of the African American middle and upper classes in Atlanta politics by turning the lens towards the poor and working class African Americans in the city.2 Even in complicating Hornsby’s narrative, Hobson reminds us of how critical it is anyone writing about Atlanta’s politics must respond to Hornsby. In addition, Hornsby’s reference books – such as Black America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia, Dictionary of Twentieth Century Black Leaders, African American Chronology: 1492–1972, Milestones in 20th Century Black History and A Biographical History of African Americans – remain indispensable resources for scholars and lay people alike. We should never ignore these kinds of reference works, which – though sometimes a thankless task for scholars – are a vital gateway into understanding a wide range of scholarly ideas for students and the wider public. Likewise, Hornsby’s mentoring of scholars such as Lavelle Porter, Jason R. Young, Frederic C. Knight, and Walter Rucker is worth noting as each of these scholars has subsequently written and researched on the southern African American experience in ways that have enriched both the fields of African American and southern studies. Moreover, his mentorship of activist and journalist Shaun King, illustrates that generous scholars can cultivate impact that takes a wide range of forms.

Putting African American voters and activists at the center of a southern political history – as Hornsby always did – instead of at the periphery or just completely leaving them out, prepares everyone to think harder about how southern politics look in the present. The 2018 midterm elections, with the rise of competitive African American candidates for state-wide office, such as Stacey Abrams in Georgia and Andrew Gillum in Florida, would no doubt have thrilled Hornsby – as both an African American southerner and as a scholar who worked for decades to put the South’s politics of race within an easy-to-understand public lens. That Hornsby treated African American political power seriously in his books illuminates a fact that far too many national journalists are only now just realizing – first with the Doug Jones victory in the Alabama special senate race in 2017, and now with the strong candidacies of Abrams and Gillum – that African American voters in the South have been, and will continue to be, a critical part of victory for any Democratic statewide candidate in the Deep South.

Regardless of how today’s midterm elections turn out, Hornsby’s work will continue to matter. For as long as African Americans constitute a crucial, and often misunderstood, part of the South’s politics, Hornsby’s work will remain relevant. One can only hope that political pundits and historians alike will crack open a work of Hornsby’s and learn something about southern, and national, politics that informs their analysis. The deep account of African American political and social agency that Hornsby’s work makes possible is the only path to effectively understand twentieth-century southern political history and twenty-first century southern political concerns.

Citation: Greene II, Robert. “On Alton Hornsby and the Politics of the Modern South.” Atlanta Studies. November 07, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20181107.

Notes

- “Professor Emeritus Alton Hornsby, Jr., first African American graduate of UT History’s Ph.D. program, 1939-2017,” The University of Texas at Austin Department of History, September 4, 2017, https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/history/news/article.php?id=12102.[↩]

- Maurice J. Hobson. The Legend of the Black Mecca: Politics and Class in the Making of Modern Atlanta. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2017.[↩]