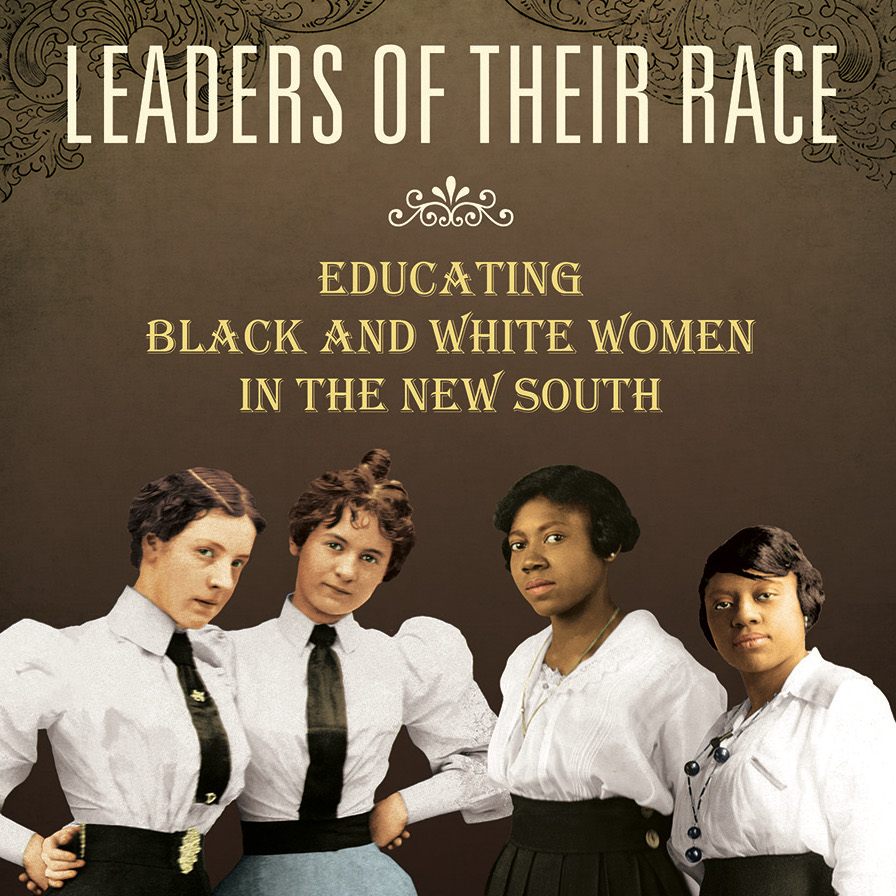

Sarah H. Case begins Leaders of Their Race: Educating Black and White Women in the New South with an 1896 quote by Henry Morehouse:

“Spelman had created women who would become ‘leaders of their own race’ – the female half of the talented tenth” (1). Case argues that although Morehouse’s “mixture of condescension and support” was typical of white seminaries, African American women believed that the “central purpose of their education was to create women who would take a leading role in contributing to racial advancement in the post–Civil War, or ‘New’ South” (1). Just as Henry Morehouse was accurate in his prediction of Spelman’s role in the development of global innovators, Case is precise in her comparison of Spelman College’s “leaders” to those of the Lucy Cobb Institute.

In Leaders of Their Race, Case analyzes how students of the Lucy Cobb Institute of Athens and students of Spelman Seminary (College) of Atlanta, used “secondary-level female education” to shape their identity, particularly between 1880 and 1925. At first, a comparison of these schools seems illogical due to the fact that Spelman was established for the uplift of newly liberated African American women while Lucy Cobb was founded for elite southern white women in order to perpetuate their southern culture, which included the continual oppression of African American women. But Case’s comparison ultimately makes a compelling argument that race, gender, sexuality, and region all intertwined to shape women’s identity (2).

The author’s “hope” for the work is twofold. First, she intends to highlight the effect that race had on the development of white and black women’s gendered identity in the New South (11). Secondly, she hopes to “acknowledge Nell Irvin Painter’s call to write history ‘across the color line’” (12). Case succeeds on both accounts.

The title of the work is potentially misleading. The word “Leaders” implies that both Lucies and Spelmanites had agency in their education. This certainly was not the case. For these women, academic and social education was determined by men. Lucy Cobb was chartered in 1859 by Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb, a “proslavery theorist,” whose goal for the institution was to perpetuate southern culture. The institution groomed leaders “for a life of domesticity and motherhood” who would become active participants in the culture, economy, and politics of the New South” (15). More importantly, Lucies were charged with maintaining their families’ social status. Although Spelman was founded by two white women in 1881, its foundation was premised on the gendered restrictions of the American Baptist Home Missionary Society (ABHMS) and the support of Henry Morehouse.1 Spelman nurtured “leaders” who would uplift their race while teaching “proper behavior” for black women – with “proper behavior” entailing that Spelmanites not only monitor their own individual sexual reputations, but also the sexual reputations of other black women. The elite white males who led these two institutions employed women to manage and perpetuate the patriarchal education of future female generations.

Case dedicates the first two chapters of her work to the historiography of the Lucy Cobb Institute, detailing the school’s 1859 inception to its closing in 1925. The question of why southern “ladies” were needed is central to the first chapter, “The ‘Perfection of Sacred Womanhood,’” which begins with a letter written to the Athens, Georgia, Watchman by an Athens mother who questions why southern girls were forced to seek education outside of their native town. The angry mother asserts that the girls “return home with minds half prejudiced against their native state . . . – Shame upon classic Athens! Shame upon the wealth and erudition of our citizens” (14). After reading the letter, Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb, the brother of its author, Laura Battile Cobb Rutherford, founded the school. Case’s well-sourced work uses newspaper clippings, Cobb scrapbooks, family papers, talks, speeches, and diaries from Cobb leader Mildred Lewis Rutherford to document the origins and early years of the institution, which welcomed white women of the “Old South planter aristocracy” following its opening in 1859. Its goal was to continue the culture of the planter elite, the “ideals of the Confederacy,” before and especially after the “Lost Cause.” Therefore, Lucies learned French, Latin, Greek, music, and art as well as that their “behavior, deportment, and reputation signified sexual purity, and class status” (12). More importantly, they learned their role in ensuring “pure blood lines,” to help maintain white supremacy.

Case highlights what Lucies learned and why they learned it in other ways as well. For example, instilling “ladylike” behavior into the students was essential to southern political power and the Democratic Party. If southern belles were not ladies, their protection from the “black beast” was not warranted, and Hoke Smith, Lucy Cobb’s brother-n-law, could not have perpetually used his “anti-black propaganda” to win Georgia gubernatorial and senate elections (35). Moreover, the conclusion of the chapter attests that Lucies were trained to continue southern white racial and class superiority through courses that “encouraged them to think about themselves and their place and their obligations to society” (42).

Chapter 2, “Clubwomen, Educators, and a Congresswoman,” explores the school’s success in getting the University of Georgia (UGA), the nation’s first public university,” to admit female students and highlights a few distinguished graduates who would impact Atlanta. Because of its close proximity to UGA, many students’ desire for a college education, and the need to increase enrollment, Cobb administrators, faculty, and students were determined to persuade college officials to allow women to attend the male only university. This eventually became a reality in 1918 when Rosa Woodberry, a Cobb graduate and later the founder of Atlanta’s Woodberry Hall for Girls, became the first female graduate of UGA (60). Besides Woodberry, Case uses this chapter to explore the lives of graduates Oneita Virginia Smith, Moina Michael, and Congresswoman Caroline Love Goodwin O’Day. These ladies’ contributions to Atlanta society and conflicts over women’s suffrage detail the education that Lucies received while fighting for white women’s social and political identities.

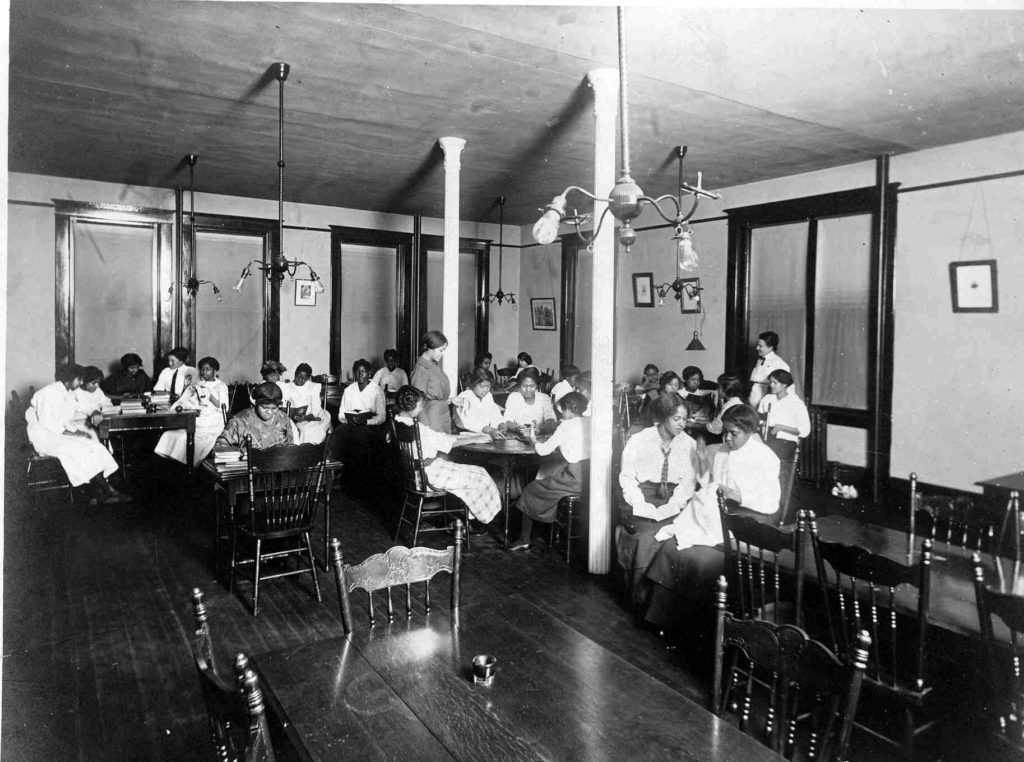

Chapters 3 and 4 mirror chapters 1 and 2, except with Spelman College as their center. Chapter 3, “Training ‘Leaders of Their Own Race’: The Educational Mission of Spelman Seminary,” chronicles the inception of the school which opened in 1881 as Spelman Seminary and welcomed African American former enslaved women and their daughters. The goals of its two northern, white, female founders – Women’s American Baptist Home Society founder Sophia Packard and her colleague Harriet Giles – were to “educate and uplift” these newly liberated women and create a female “talented tenth.” However, drawing on Giles’ diary, Case asserts that although Spelman founders did not publicly voice racist views, they nonetheless felt that “African American students needed the help of Christian white women for their moral and behavioral uplift” (88). Accordingly, while Spelmanites’ education was industrial and academic, they also learned character virtues, chastity, and respectability. In particular, they learned that individual respectability could be used to demonstrate the “worthiness of black women as a whole, and the readiness of African Americans as a group for full citizenship rights and privileges” (12).

Case’s book also acknowledges the influence that Father Frank Quarles of Friendship Baptist Church, and William J. White of Augusta Baptist Institute (Morehouse College) had on Spelman’s beginning. Unlike Lucy Cobb founders’ fixation on perpetuating antebellum culture, Spelman’s founders developed alliances with community leaders to agitate for social, political, and economic change. Case’s depiction of this contrast is the jewel of her work. She details the diversity of the faculty, preachers, and laypeople; Spelman’s attraction and admission of most students; the broad range of students’ ages; the diversity of the industrial and academic education; and most importantly, the diversity of financial support. For example, while Quarles led a New England fund-raising tour, Packard and Giles sought assistance from John D. Rockefeller, T. J. Morgan and of course the ABHMS. Chapter 4, “Respectability and Reform,” mirrors chapter 2 in highlighting a few of Spelman’s distinguished alumnae. Selena Sloan Butler, Claudia Sloan White Harreld, Sue Elvis Bailey Thurman, and Alberta Williams King are among the notable Spelmanites who through their roles as educators trained students to fight for civil and human rights.

The 125-page work, complemented by fifteen rare archival photos, is filled with insightful commentary on gender, class, and race in secondary education in Georgia around the turn of the twentieth century. Its study will benefit advanced placement high school and undergraduate college students as well. And graduate students can use the text to hold valuable discussions from its recurring themes of sexuality restraint and its role in shaping women’s identity.

Citation: Shannon, Lisa. “Book Review: Leaders of their Race.” Atlanta Studies. March 22, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20180322.

- David Charles Laubach, American Baptist Home Mission Roots 1824–2010 (Valley Forge, PA: American Baptist Home Mission Societies, n.d.), 26, http://abhms.org/about-us/history/.[↩]