Ever since Georgia State University moved into the Bolling Jones Building (now called Kell Hall) on Ivy Street (now Peachtree Center Avenue) in 1947, the university has left an indelible mark on downtown Atlanta.

In the following decades the university grew steadily, but haphazardly, until the 1990s when GSU President Carl Patton introduced the Main Street Master Plan (see some of the changes in this storymap that GSU has created about their expansion, a screenshot of which is pictured to the right). 1 With a background in urban planning, Patton crafted a blueprint for GSU’s growth. With a background in urban planning, Patton’s plan sought to build a “true” campus for GSU by connecting its disparate parts into a contiguous body. Following its introduction, Patton hailed the university’s expansion and student population increase as an economic boon to downtown Atlanta specifically as it “pushed up the price of real estate for the university and other stakeholders.”2 Since implementing Patton’s Main Street Master Plan, GSU has acted as a major real estate developer and an anchor institution for the economic development of downtown Atlanta.

The university has continued to play a large role in the development of the eastern side of downtown Atlanta since Patton’s retirement in 2008. Most notably the university purchased the Beaudry Ford dealership and constructed the University Commons, which houses 2,000 students and expanded the university’s footprint north along Piedmont Avenue. This purchase is notable for a few reasons. Most importantly, it brought a large number of residential students to the downtown campus and allowed the university to sell off the former Olympic Village located on North Avenue. Secondly, it expanded GSU’s reach beyond its traditional DeKalb Avenue corridor north along Piedmont Avenue. More recently, GSU is in the news for expanding its footprint once more, this time via its purchase (in partnership with real-estate firm Carter) of Turner Field south of its main campus along Piedmont Avenue.3There has been much debate and some protests about the initial development plans that were announced by GSU and Carter.4 Residents in the neighborhoods surrounding Turner Field were concerned that property values would rise and lead to their displacement.5 In response to these concerns, GSU and Carter introduced a new plan in late April with significant buy-in from neighborhood organizations like the Organized Neighbors of Summerhill, Grant Park Neighborhood Association, and others.6Now the $30-million question is how the proposed mixed-use development will affect the area surrounding GSU Stadium (née Turner Field) economically. Answering the question may be best done by examining GSU’s past as a real estate developer in downtown Atlanta, which means examining the properties around the university’s primary campus along Decatur Street and Piedmont Avenue.

GSU’s History As An Anchor For Economic Development

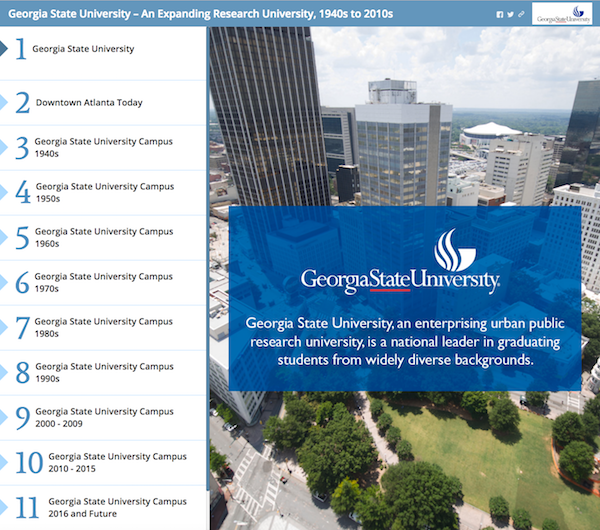

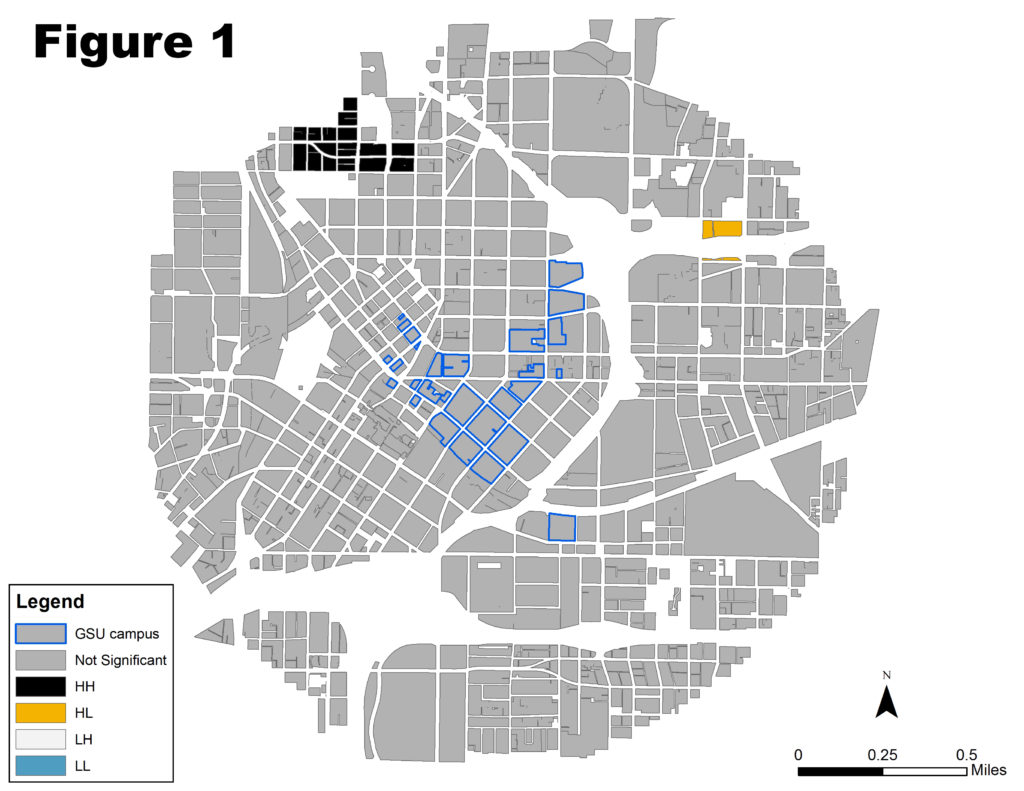

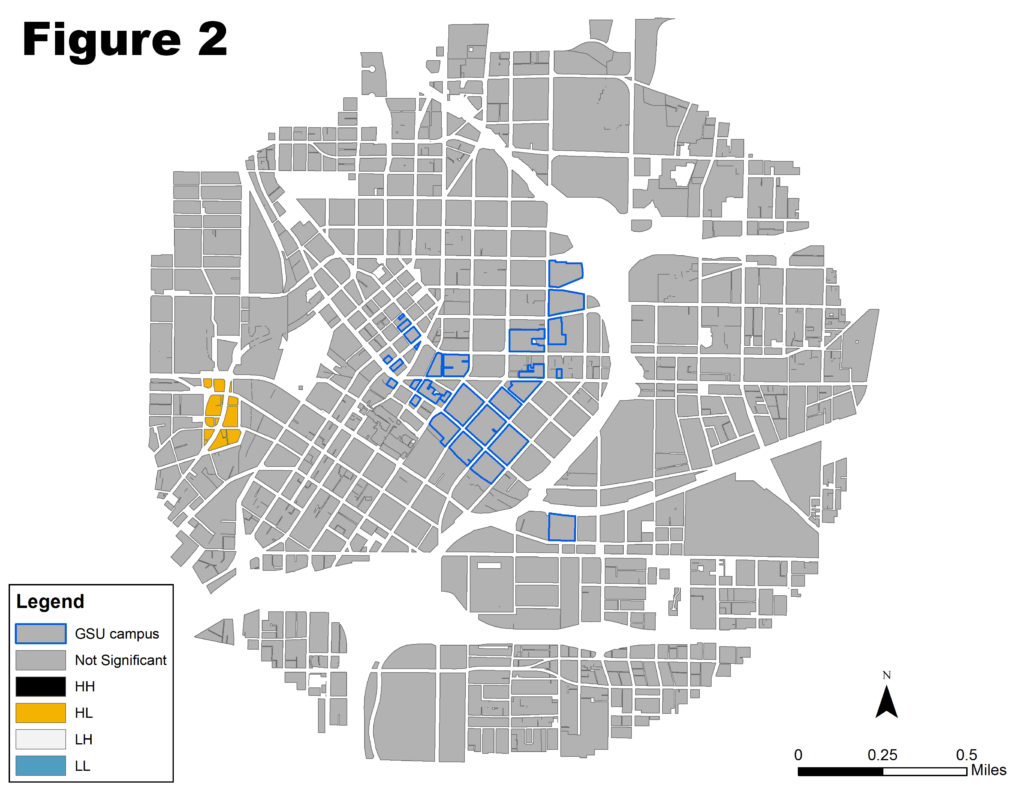

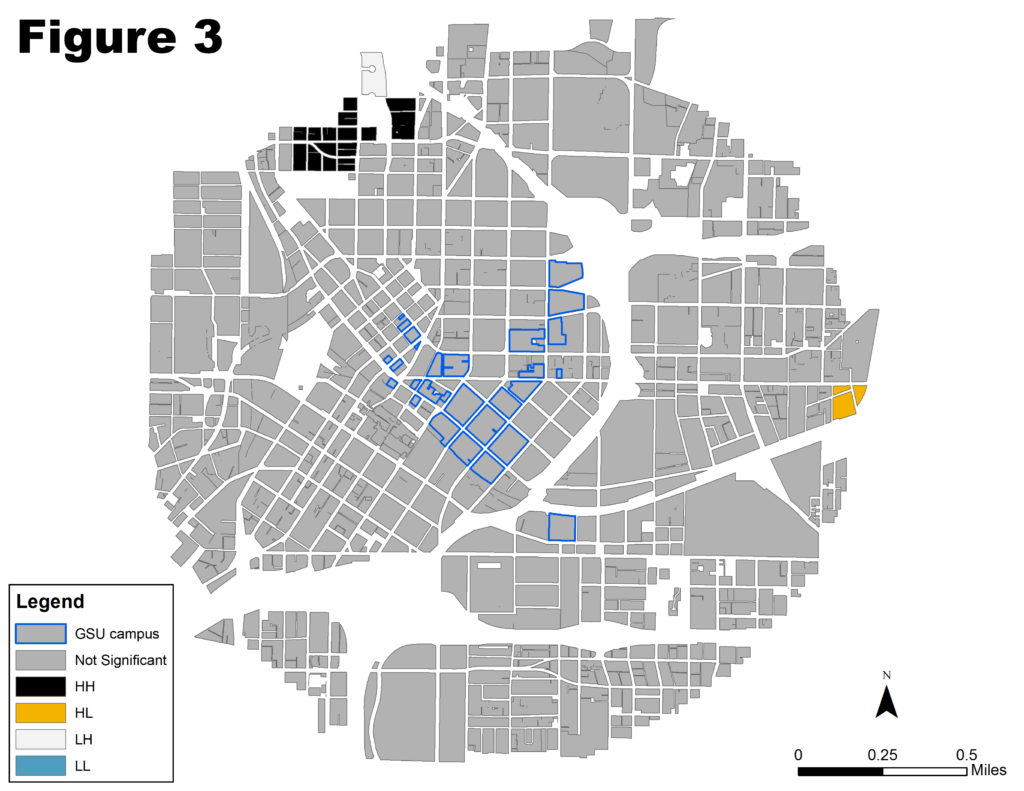

I have studied GSU’s economic impact on downtown Atlanta, examining how the expansion of the university’s physical footprint and growth of its student population from 2000 to 2012 affected real estate values.7 Using a method called spatial autocorrelation, my work tried to locate statistically significant outliers where property values either dramatically outpaced or lagged behind surrounding land parcels.Examining the change from 2000 to 2007, my analysis showed no significant impact surrounding the GSU campus (Figure 1). In fact, the only area with significant increase in property values neighbored Centennial Olympic Park, and the parcels belong to Centennial Place Apartments. Likewise, my analysis of change from 2007 to 2012 showed that the majority of properties within a one-mile radius around the GSU campus had no significant property value change (Figure 2). When I examined change from 2000 to 2012, the results showed similar findings to the analysis of change from 2000 to 2007. There was a statistically significant increase in property values north of Centennial Olympic Park and east off DeKalb Avenue, but those parcels are apartment complexes that were not built in connection to the geographic growth of GSU nor the increase of its student population (Figure 3). So it appears that GSU’s expansion and student population growth have not significantly impacted the property values of its neighbors.

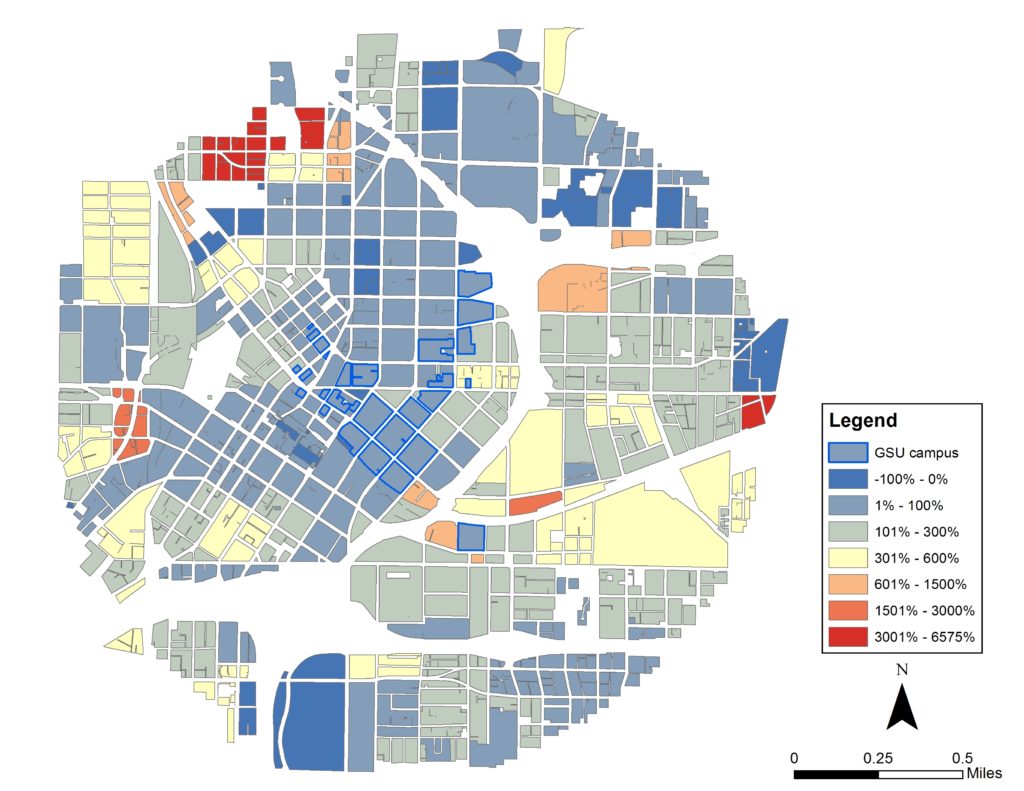

The analysis would seem to paint Georgia State in a negative light as a real estate developer in downtown Atlanta because no properties that immediately border the university campus saw significant increase in value over the twelve-year period. However, a sliver of hope is revealed when examining the percentage of change in property values from 2000 to 2012 (Figure 4 below). This data shows that many of the properties surrounding the GSU campus increased in value during the study period. In many cases, the surrounding parcels saw similar increases in property value, which results in the lack of statistically significant increases conducted with spatial autocorrelation. Spatial autocorrelation finds outliers (either high values surrounding by low values or low values surrounding by high values), but when an entire area sees similar changes in property values there is no statistically significant change.

Conclusions

So did GSU really impact property values surrounding its campus in downtown? The answer to that question is unclear. My analysis showed there was no statistically significant change from 2000 to 2012, but digging deeper into the data revealed that there was an increase in property values just not one that met the standard to be considered statistically significant. Can the increase in property values be attributed to GSU’s growth? Perhaps property values rose in accordance to changes in the economy regardless of GSU’s expansion in downtown. Just examining property values, it is not possible to quantifiably answer whether GSU’s growth in downtown Atlanta increased property values of surrounding land parcels.

What does this mean for the future of economic development around GSU Stadium (the former Turner Field)? It is difficult to say because GSU’s growth has helped increase property values in downtown Atlanta, but it has not done so at significant enough levels to cause a dramatic change in property values. Additionally, the Main Street Master Plan focused specifically on building academic buildings and student housing with only a minimal attempt to incorporate consumer services. In contrast, the new development at what used to be Turner Field has a completely different objective. Perhaps the biggest difference will be the buy-in from neighborhood organizations. If area residents shop at the consumer services as part of the development more services can develop, which will support the community and create a true economic engine for development instead of just another stadium project.

Citation: Ericson, Steven P.. “Will GSU’s Repurposing of Turner Field Be an Engine for Economic Development?.” Atlanta Studies. July 13, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20170713.

Notes

- Georgia State University, “Main Street Master Plan Update 2005-2015,” 2006, http://www2.gsu.edu/~wwwmsp/index.htm.[↩]

- Lawrence R. Kelley and Carl V. Patton, “The University As An Engine For Downtown Renewal In Atlanta,” in The University As Urban Developer: Case Studies And Analysis, ed. David C. Perry and Wim Wiewel (Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2005), 144.[↩]

- Janel Davis, “Georgia State, Partners Reach Deal To Buy Turner Field for $30 million,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 18, 2016, http://www.ajc.com/news/local-govt–politics/georgia-state-partners-reach-deal-buy-turner-field-for-million/TWngBHG7wWVfm17fJpwSiO/.[↩]

- Chris Price and Ashley Thompson, “Turner Field Residents Fight Displacement As Development Ensues,” CBS46.com, February 28, 2017, http://www.cbs46.com/story/34625118/turner-field-residents-fight-displacement-as-development-ensues.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Leon Stafford, “GSU-Turner Field Neighborhoods Strike Deal To Address Community Change,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 24, 2017, http://www.ajc.com/news/local-govt–politics/gsu-turner-field-neighborhoods-strike-deal-address-community-change/RM4aSNuQcPytuWNTQTpDDO/.[↩]

- Steven P. Ericson, “The Impact Of An Urban University And Its Neighborhood: A Case Study of Georgia State University and Downtown Atlanta” (PhD diss.), 8-38.[↩]