We recently sat down with longtime Atlanta Studies contributor and southside resident Hannah Palmer to discuss her new book, Flight Path: A Search for Roots Beneath the World’s Busiest Airport.

Part memoir and part urban history, Flight Path explores the continued expansion of Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport and the erasure of southside neighborhoods in the path of its development, which included all of Palmer’s childhood homes. The first chapter of Palmer’s book is available read on the Atlanta Journal-Constitution website. In the interview Palmer speaks about the book’s backstory, the circumstances that shaped it, and what comes next for our favorite “southside observer.”

How and when did you begin writing this book?

I started a blog about the southside called Stumptown in 2004 when I moved back to Atlanta after several years in Brooklyn. It was just a blog, it was just me kind of riffing and asking questions and posting ideas. There was no direction for it. But over the years – and I was posting maybe once a month, chronicling things as they were disappearing – over time I realized that no one else was covering this beat so I started to feel some ownership over it, especially being from the southside myself. When I entered the MFA program at Sewanee in 2008 I had this bulk of material and I thought, “this could be a long form project.” I deliberately started writing some longer essays and doing deeper research as a graduate student in creative writing. This book, as it is now, is substantially my MFA thesis project. And then when Hub City Press bought the manuscript they wanted me to do some additional thinking and writing and expand on it. I think I wrote about three more chapters with the publisher’s suggestions in mind.

Were there any major changes to the book during the long evolution of this project?

At first it was just a series of essays but then when I got pregnant that gave a timeline and a narrative spine to the book project. I decided to limit my investigations to the nine months of pregnancy – I wanted to see what I could learn about these places before I became a parent. My idea was that when you are about to become a parent you have this nesting instinct and you also have a kind of panicked moment where you realize you are going to be responsible for raising someone and teaching them about the world. And I thought I would just apply that energy to this investigation also knowing that in nine months I was going to have a baby and I wouldn’t have the time to work on the book. And I’m still trying to understand what happened to my houses, what happened to the southside, how the airport – and not just this airport – but how airports all over the world and other kinds of infrastructure projects influence their communities. But the book needed an end, so I used my pregnancy to give it that.

Another change was that after I finished the MFA thesis project, I shared it with a friend who is an urban designer. He was moved by it and appreciated my approach and actually hired me to join an urban design team as a researcher, writer, and storyteller. Over the course of the next few years I worked intensively with urban planning and design teams and found a whole new vocabulary to articulate the things I was observing just as a citizen and as an artist. So when it came to the additional research I added to the book once I found a publisher, by then I had the tools of an urban designer under my belt, which included new research methods and additional vocabulary to talk about what I was seeing.

So I started the process as a curious blogger and by the time I finished it I was working as a professional urban designer.

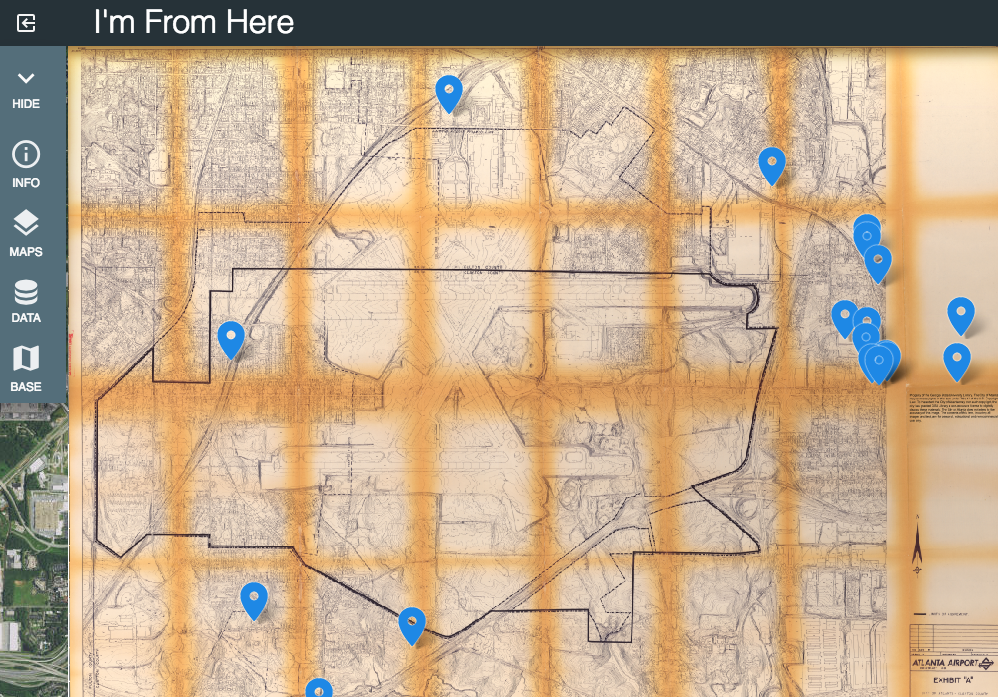

About two years ago you wrote a post for us that dealt with whether Hartfield-Jackson was “unloveable.” You also created of an ATLMaps layer about the very story of erasure at the heart of your book. I was wondering if you could tell us a bit about how the process of building that map layer might have impacted this book?

Right now my Facebook author page cover image is actually a screenshot from the ATLMaps layer project, so it’s meant a lot to me. In the book I recount the first time I ever used Google Maps’ satellite view. It was revolutionary to be able to see the world the same way that pilots see the world or the way planners see the world. I try to express that in the book – this need to “see it from above.” Because when you grow up in Forest Park, and there are airplanes landing on top of you, you have zero concept of the scale, of the importance, of the design of your next door neighbor, which is the world’s busiest airport.

In the book I talk about how once satellite maps became part of our lives we start asking bigger questions and for more information, and have this need to see before and after. Google Earth has now evolved to the point where you can see some historic imagery, but what Georgia State provided with in their archives were planning maps of the airport area back to the 1960s. And seeing the neighborhoods surrounding the airport in the 1960s and then scroll through and see today’s concourses is to see literally the erasure of the city of Mountain View and huge chunks of Hapeville and College Park. It’s breathtaking. You can see all that was lost. When I show that overlay to people in presentations it brings people to tears. It’s powerful evidence that these places existed and that story hasn’t been told for forty years. Previously there hadn’t been any way to visualize all of the neighborhoods had been lost. I was wishing for that ability and so it’s been meaningful to have Brennan Collins and the team at Georgia State help me build the layer for the story I was trying to tell using the ATLMaps platform.

What influenced you to make this a memoir rather than a manifesto, or one of the many other forms you could have used to tell the story of the airport’s destruction of southside neighborhoods?

I think there should be many books about the airport. Mine might be the first but it certainly won’t be the last. I hope it opens a new conversation and that people with different areas of expertise weigh in. I chose to write about it in the way that I did because you write the book you want to see in the world. I read a lot of memoir and creative non-fiction. I think in some ways memoir is the Trojan horse for talking about complicated and far-reaching issues, such as race or displacement. And I just felt overwhelmed by trying to tell everyone’s story. I think historians are burdened with telling the story of an entire population, an entire area, an entire period, and I couldn’t even begin to take a bite out of all of that. I thought: if I just stick with what I know – my personal story – and I tell that in a way that is very physical, very intimate, then other people are going to see their own stories in that. Because that’s how I read. I read memoirs about places I will never visit and lives I will never inhabit, but if I walk in the shoes of one person it opens a whole other world for me. And that has been the reaction I’ve gotten from so many people who’ve reached out to me on Facebook saying: “that happened to me too,” “that happened to our house and our family.”

Earlier you mentioned how your pregnancy gave you a “narrative spine” for the book and I was wondering if you could tell us whether you see your perspective as a woman and now a mother shaping your critique of the airport’s development? And if so, how?

Throughout the book a lot of the people that I’m interviewing and questioning are men. The property owners, developers, designers, planners, the firemen, the administrators – they were all men. And I couldn’t help but develop this sense that the airport was dreamed up by and designed, planned, and built for men. The women that I talk to in the book tend to be the people who were trying to make a home in this area and who work as caregivers, moms, grandmothers. So I was acutely aware of my position as a woman – and at times in the book I’m a very visibly pregnant woman – questioning men about this landscape. I’m walking into a room full of men with my belly first feeling very self-conscious about that. But also, over time, I came to embrace my position as a usefully different perspective on home and what home means. Because my body was becoming home for a person.

I’m not a particularly sentimental person. I am more forward-looking, and I didn’t want my book to be just a nostalgic trip down memory lane or something. I didn’t have the happiest childhood. I just had some questions about the landscape and who dreamed this up: Whose idea was this? Was there a vision for Forest Park, my hometown? What was that vision? That was a mystery to me. I found that the men who I talked to viewed these properties, houses, and runways as professionals. They had an utter lack of sentimentality or nostalgia. These were business deals. These were projects to be executed. And they took a lot of pride in what they had accomplished. Whereas the women who I spoke to bore the devastation. They seemed to speak of homes they had built and had lost. It was a profoundly gendered divide in terms of the kinds of conversations I was having. And it helped me in a way to talk to the developers and airport designers and feel a sense of excitement and pride about what had been accomplished, but to still know personally what was lost.

Now that the book is out, what comes next? In your recent blog post for us you discussed televisual representations of the southside and the area’s complex relationship to “mainstream Atlanta” so I assume that might continue to be a geographic site of interest, but I was wondering what specific issues you are looking to explore next?

Right now I’m engaged in a number of projects that are about repressed waterways and watersheds in Atlanta. I’m looking into the stories surrounding the Flint River headwaters, which begin right underneath the “World’s Busiest Airport.” We are just emerging from an era when water has been channeled and repressed in our urban environment and increasingly cities are now turning back to their natural assets to both create healthier urban ecosystems and to connect people to nature and their history. It seems inevitable to me that Atlanta is going to begin to embrace these hidden waterways again as actual assets and not just as flooding problems. Whether it’s the South Peachtree Creek, the Chattahoochee river, or Proctor Creek – there are just so many – I’m fascinated by how that’s now happening because it tells a story of why our city is shaped the way it is and how we’ve hidden away our natural resources.

Citation: Newman, Adam P. “Viewing the “Flight Path” from Stumptown – An Interview with Hannah Palmer.” Atlanta Studies. April 04, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20170404.