Old habits die hard.

In recent days, discussions over the relevance of “lost cause” symbols have flooded social media and news outlets with discourse over “heritage or hate.” These discussions come after neo-confederate Dylann Roof’s massacre of nine black church members at the historic Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, just a stone’s throw away from the grounds where the American Civil War began. In the days after this hate crime and the subsequent capture of Roof, it became clear that the misguided youth had written a hateful manifesto promoting white supremacy and his disdain for non-white people. Roof had even gone as far as to champion international orders of white supremacy, donning apartheid flags of Rhodesia and South Africa. These international flags are indefinite symbols to the untrained American eye, but his picture with a pistol in one hand and the Confederate battle flag in the other paints a clear picture that America understands, pure old-fashioned HATE. Still, the debates over the meaning and relevance of “lost cause” symbols are still alive and well in the American South. As of today, seven southern states still honor the “lost cause” of the Confederacy through their state flags. 1

An often overlooked debate over “lost cause” symbols has been waged by the self-defined southern-style of rap and hip-hop culture called Dirty Southern hip-hop. Invented and promoted in the early and mid 1990s by southern artists, this movement championed hip-hop, but explicated southern regional markers that define differences. Though regional by definition, the term Dirty South has been appropriated by a larger black community for connotations of the past injustices of black southern life redefined in endeared terms. Dirty South artists brought forth vibrant and diverse narratives of the past and present black South and experimented with the use of the controversial Southern Cross.

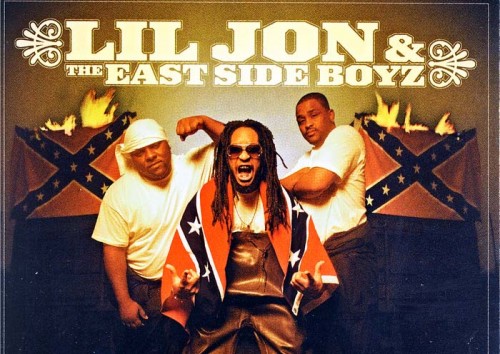

Examples of this can be seen through OutKast’s Andre Benjamin sporting a Confederate battle flag belt buckle in the “Ms. Jackson” music video or the cover of Atlanta’s Lil Jon & the Eastside Boyz album entitled “Put Yo Hood Up” where Lil Jon draped himself in the controversial battle flag with two more flags burning in the background. An even clearer example of black southern identity in hip-hop was Mississippi’s David Banner’s appropriation of the Confederate battle flag, changing the color to red, black and green, the colors of the Republic of New Afrika, a social movement based on black nationalism and the formation of a black majority country made up of southern states. 2

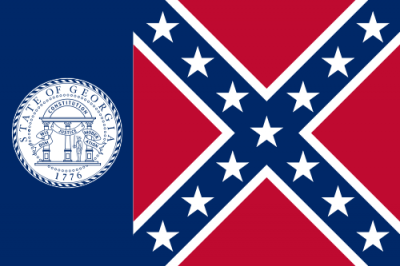

Just as Lil Jon seems to both wear and reject southern identity as represented through the confederate flag, Andre Benjamin’s wearing of a Confederate belt buckle in 1999 is complicated by the earlier OutKast track entitled D.E.E.P., from the 1994 Southernplayalisticcadillacmuzik album. Here, Benjamin raps, “Oh and Mayor [Jackson], can I get a little backup? Please don’t let them p#$$y motherf*(K3rs put that flag up!!” Here, his lyrics speak to the politically charged issue of the Confederate battle flag symbol on the Georgia state flag from 1956–2001. While Benjamin can use the Confederate symbol in a belt buckle to show an ambivalent embrace of southern identity, his commentary suggests that the flying of the Confederate flag to represent the state of Georgia is unacceptable. This blog post chronicles the showdown over “lost cause” symbols as Atlanta prepared to host the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games.

In 1956, the Navy Jack was added to the state flag as the recalcitrant white response to the Supreme Court’s Brown decision to desegregate schools. The flag represented the South’s resistance to federal mandates for civil and political equality. 3

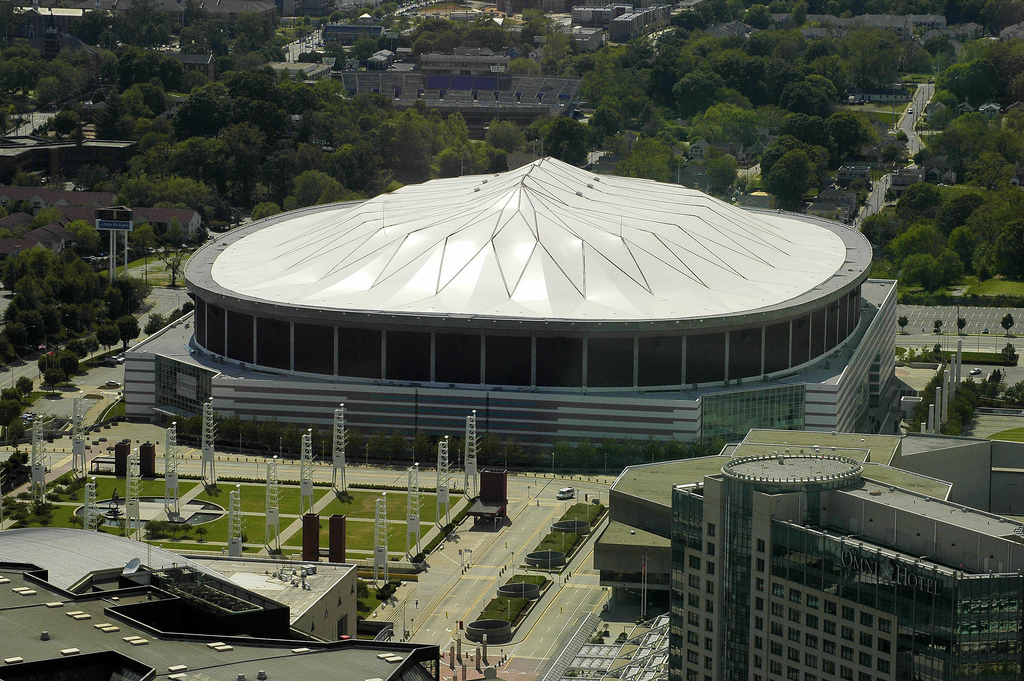

As Atlanta moved forward in preparing for the Olympic Games, the city, state and region were forced to confront negative markers of white supremacy. In 1994, Atlanta’s state-owned Georgia Dome played host to Super Bowl XXVIII. In the days preceding the event, Atlanta councilwoman Carolyn Long Banks raised the issue, as the Georgia state flag flew atop local, state, and federal buildings.

To Atlanta’s blacks, the Georgia Dome was built on the foundation of the black community, the historic Vine City district on the western edge of downtown across the way from the Atlanta University Complex and home to some of Atlanta’s roughest and most destitute areas. The Deep South’s newest and most modern world-class and international city bore witness to progress, yet the fruits of this success were not, and have never been, shared equally. Poor blacks had benefitted little from the events of the previous two decades. Atlanta’s poor and working class had reaped few material rewards from the re-creation of Atlanta leading up to the Centennial Olympics. As black and white political and business elites polished and perfected Atlanta’s new image for world consumption, they remained trapped by poverty and neglect.

Just prior to the Super Bowl, Congressman John Lewis blasted the NFL and some Atlanta politicians for not demanding the removal of the state flag during the game as it misrepresented the city. As early as 1993, Governor Zell Miller raised the issue of changing the state flag before 1996, but scrapped the idea after it was met with resistance from the legislature. To bring attention to the issue, state senator Ralph Abernathy III planned a noon march to protest the flag on Super Bowl Sunday.

In February of 1994, the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium removed the Georgia State flag bearing the Navy Jack symbol from atop the stadium. Fulton County Commissioner Michael Hightower, a member of the Atlanta-Fulton County Recreation Authority responsible for the vote that took down the flag asserted that this decision was made with hopes that all minds be brought together as the city moved toward the 1996 event. However, Georgia lawmakers across party lines had mixed reactions to the removal of the flag from the stadium. In both parties, white lawmakers thought it was “bad judgment” to remove the flag. Black political leaders, as well as those preparing the city for the Olympics praised actions taken at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. With this, they predicted that more venues and public buildings would take similar actions.

The Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games (ACOG) asserted that the flag was an issue that transcended the games and embodied a long discourse on southern politics and race. As such, ACOG suggested that Georgia’s political leaders handle this matter. Around the same time, the decision by Stone Mountain Park officials to eliminate the playing of “Dixie” and images of the Confederate battle flag in the park’s laser show was considered to be a critical issue in the 1994 gubernatorial race.

As Atlanta moved towards the Olympics, the flag issue heated again involving international relations in the form of world-class athletes and diplomats. The threat of protest by African American athletes had far-reaching implications well beyond politics and into the realm of economics and sports. Sports pages would be dominated with extensive analyses of America’s most glaring social ill, racism. Morality and conscience would supplant terms such as ticket sales and competition. Allegations of racism and self-righteousness would compete with the Dream Team III for prime play and witty headlines and Team USA’s cache of gold would be tarnished by the unprecedented exposure of America’s greatest embarrassment.

Though not yet selected, black American athletes were sure to protest if the Navy Jack version of the Georgia state flag flew atop venues in which they were to compete. Atlantans and former Olympians Teresa Edwards and Katrina McClain expressed disappointment, anger, and surprise that the Confederate battle flag would represent their city. Olympic officials anticipated some forms of civil disobedience. The possibility of athletes’ symbolic demonstrations, or worse, the altogether boycott of the Games, was a real threat to Atlanta’s image.

In the days just before the opening ceremonies, twenty protesters carrying Confederate Georgia state flags, including members of Georgia’s “lost cause” groups the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the Heritage Preservation Association gathered in front of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution building to condemn the newspaper and ACOG for what they said were efforts to ban the flag from Olympic venues. Staunch segregationist and former governor Lester Maddox led the group. They cited the newspaper’s editorial policy advocating removal of the St. Andrew’s Cross from the flag, and ACOG’s decision not to include flag pins in its collections of Olympic pins. While protesting, the former statesman Maddox carried a sign that read, “You Too Can Become a South Hater. Simply Join ACOG Leaders and the Atlanta Constitution and Oppose the Georgia Flag.”

The 1956 flag was never banned from the Games, but many acquiesced and made the flag less visible for world consumption.

Andre Benjamin and other Dirty South artists have irreconcilably appropriated “lost cause” symbols to explore more possibilities of black southern identity, but Benjamin’s lyrics unambiguously condemn the Southern Cross as an official state symbol. The Olympics forced Atlanta and the American South to reconsider what these past negative images meant for business. Atlanta’s commercial branding and its imagery as the Black Mecca, the city too busy to hate, and Hotlanta were created to show a city bigger than the region’s sordid history of race relations. Yet, it is still fighting the “lost cause.”

Through executive action in 2001, Georgia Governor Roy Barnes removed the Southern Cross of the second national flag of the Confederacy from the state flag to show Georgia as progressive in race relations. White recalcitrance reared its ugly head again in 2002. The election of Governor Sonny Perdue is often understood as backlash to Barnes’ actions. Perdue wanted to put the flag to a referendum, but ran into a catch. The Georgia Constitution states that the flag is to be determined by the General Assembly, so a popular referendum was out of the question. The Georgia Assembly then voted to change the 1956 flag to one based on the first national flag of the Confederacy: switching Dixies. 4

Thus, Atlanta’s modern image as the Black Mecca and Hotlanta, as seen through the Olympics, boomed, in part to black southerners seizure and manipulation old southern markers – with Dirty South’s hip hop being the latest in the long standing tradition of “Atlanta’s style bi-racial of negotiation.” 5

Citation: Hobson, Maurice J.. “Switching Dixies: Atlanta, Neo-Confederates, and the Centennial Games.” Atlanta Studies. July 09, 2015. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20150709.

Maurice Hobson is an assistant professor of African American Studies at Georgia State University. Learn more about these issues in Hobson’s book The Legend of the Black Mecca: Myth, Maxim and the Making of an Olympic City, forthcoming from the University of North Carolina Press.

Notes

- These states are Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Tennessee.[↩]

- These states include Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina. This idea was based the fact that the soil of these states had been watered by the blood and struggle of black folk in America. Florida was not included because that was Seminole land.[↩]

- See Edwin Jackson, “State Flags of Georgia,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/government-politics/state-flags-georgia.[↩]

- The “Stars and Bars” is often confused with second national flag, which includes a cross that forms an X known as the Navy Jack.[↩]

- A term coined by scholar Tomiko Brown-Nagin.[↩]