The following is the fourth and final installment in a series of guest blog posts that complement Charles Steffen’s recently published article “The Rise and Fall of Atlanta’s Skid Row” by highlighting the continuing pertinence of those issues in Atlanta today.

In his article, “The Rise and Fall of Atlanta’s Skid Row,” Charles Steffen remarks that in 1974 “[f]rom his office at City Hall, [Maynard] Jackson could survey [a] jarring juxtaposition of poverty and power, grime and grace,” that defined this one central area in the wake of white flight. South Downtown was home to various spectacles of such power, including those at City Hall, the Georgia State Capitol, and the Fulton County Court House. Yet, with the holiday season upon us, one particular display of grace from the history of South Downtown illuminates the profound inequalities that the area bore witness to: the lighting of Rich’s Great Tree on Thanksgiving.

As author and journalist Celestine Sibley writes in Dear Store, her history of Rich’s department store published for the store’s centennial in 1967: “Whatever the origin, every Christmas since 1948 people approaching Atlanta from any direction have seen high on the skyline the shimmering lighted presence of a real Christmas tree.” 1 Though unknown by many younger Atlantans today – especially in the wake of the Great Tree’s migration first to Underground Atlanta in the 1990s and then up to Lenox Mall in the 2000s, where it has now been reduced to an artificial tree in a parking lot – from the 1940s through the 1980s Rich’s Great Tree was a vital part of the South Downtown skyline every holiday season.

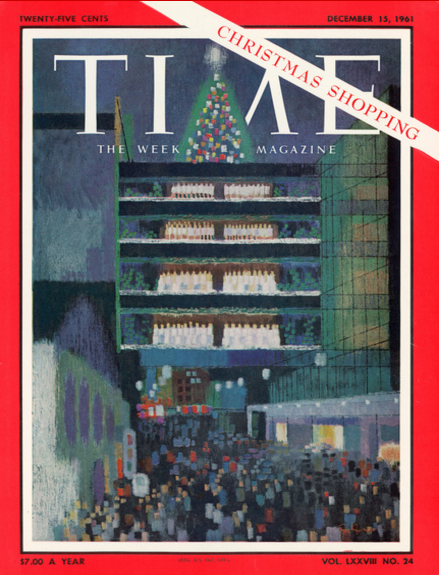

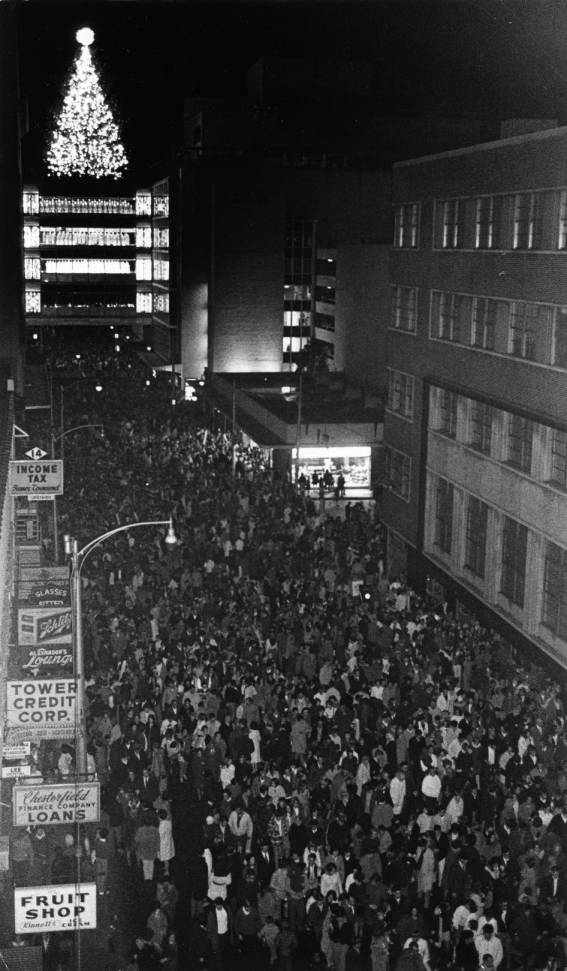

Rich’s Great Tree was not only a local attraction. As pictured above, the tree graced the cover of Time magazine itself in 1961, illustrating that issue’s cover story, “But Once a Year,” about department stores’ major role in the increasing commercialization of Christmas. As illustrated by the 1969 photo to the left, however, over those forty years in which Rich’s Great Tree shone downtown every holiday season it was merely not some crass symbol of consumption or nothing more than a seasonal accoutrement the city’s skyline for Atlantans. Rather, the lighting of the tree, which always took place on Thanksgiving, was a spectacular event that drew massive crowds to South Downtown, even as the neighborhood itself changed dramatically over that period. And though this spectacle might have been hosted by a department store, as Celestine Sibley and many others attested to, the sense of community it engendered was genuine. As Sibley notes: “From the Big tree a radiance reflects on the faces of children standing below in the darkness and sometimes it makes prisms of tears on the faces of grownups.

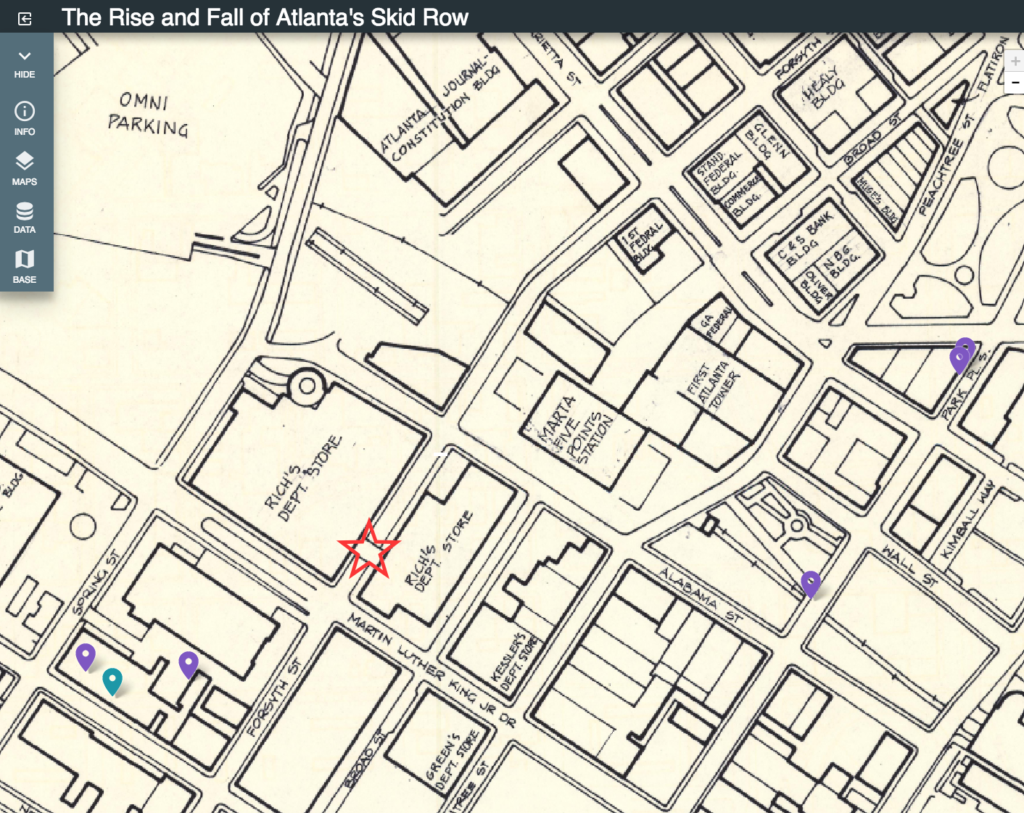

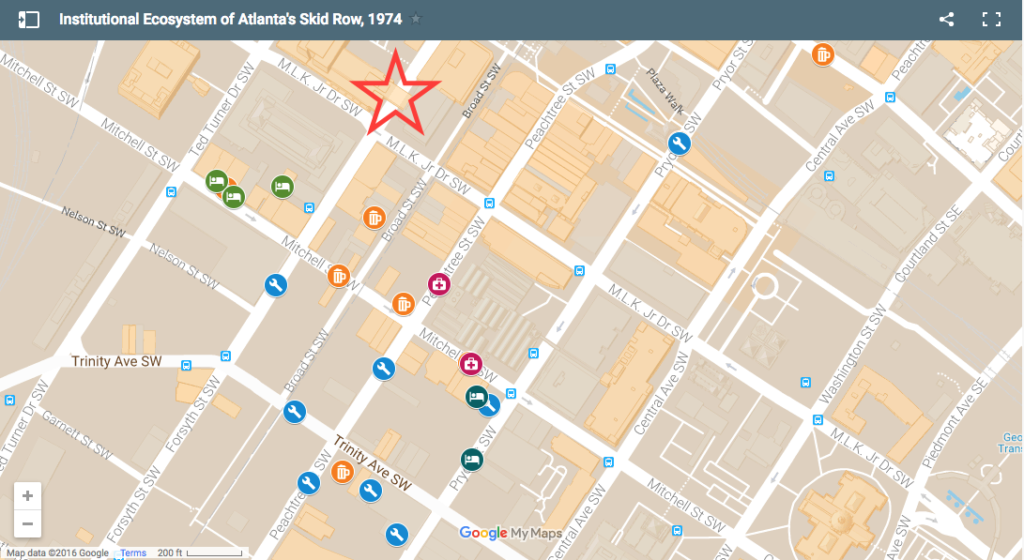

Christmas has officially begun in Atlanta.”In light of Steffen’s narrative of South Downtown’s evolution into Atlanta’s Skid Row over those same forty years, however, this spectacle of grace, usually invoked purely for nostalgic purposes, now exposes the inequalities that have attended Atlanta’s postwar development, even those once hidden by the lights of Rich’s Great Tree. For as the screenshot below on the left illustrates, in the 1970s–1980s there were six different Single Residency Occupancy (SRO) hotels within just three blocks of Rich’s Great Tree (marked by a red star) each holiday season. Moreover, as illustrated in the screenshot below on the right, the dense network of SROs, mission houses, labor pools, blood banks, and cheap bars that Steffen quotes Atlanta Constitution reporter Jim Merriner as having called a “treadmill of despair for winos” was just one block south of Rich’s Great Tree (again marked by a red star). The proximity between these institutions that simultaneously supported and exploited Atlanta’s homeless and the site for one of Atlanta’s most cherished Christmas traditions forces us to reassess the spirit of those massive holiday crowds that packed Forsyth Street each Thanksgiving to watch the Rich’s Great Tree lit up upon the Crystal Bridge, and ask ourselves not whether their joy was genuine, but rather if it depended on ignoring the needy who were quite literally in their midst.Screenshot from ATLMaps Layer “The Rise and Fall of Atlanta’s Skid Row.”

Citation: Newman, Adam P.. “Christmas in South Downtown.” Atlanta Studies. December 22, 2016. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20161222.

Notes

- Celestine Sibley’s Dear Store: An Affectionate Portrait of Rich’s. (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1967), 138.[↩]