In March 2008, a tornado ripped through downtown Atlanta.

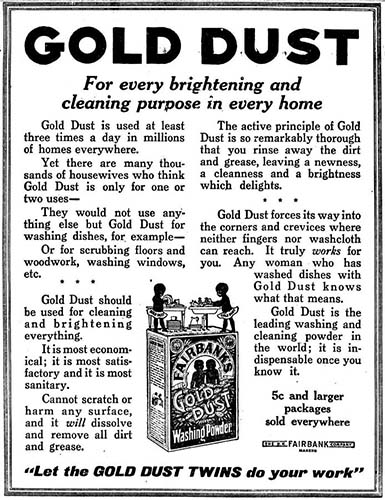

Damage totaled around half a billion dollars. One life was lost. Amid the destruction came the resurrection of an early 20th century billboard—a caricature of coal-black, wide eyed, tutu-wearing twins, happily scrubbing dishes. The two were the Gold Dust Twins, the nationally recognized trademark for Gold Dust Washing Powder, a household cleaning product whose popularity soared with the antics of the cheerful, degraded duo.

The advertisement is painted on the exterior east wall of a vacant, three-story brick building at 229 Auburn Avenue. 1 The structure was once the local office of the Atlanta Life Insurance Company, founded in 1905 by Alonzo Herndon, one of the wealthiest African Americans in the South at the time. For more than eighty years the Gold Dust advertisement remained hidden from view, obstructed by the neighboring Herndon Office Building, completed in 1926. When the tornado-damaged Herndon Building was demolished in 2008, the advertisement came to light, raising difficult questions of race and culture—and more pressing, what to do with the twins now that they were back.

Created by Fairbanks of Chicago

Gold Dust Washing Powder was the brainchild of the Nathaniel K. Fairbanks Company of Chicago. Established in 1864 as the Fairbanks, Peck & Company, it employed 160 men, women, and children and produced about $2 million worth of lard, soap, and cottonseed oil a year by 1870. In 1875 the American Cotton Oil Company purchased Fairbanks and renamed it N.K. Fairbanks & Co. By 1880 the new company had 400 employees and $5 million in annual sales. 2

Early advertisements of the washing powder featured young white women, hair hidden under scarves, scrubbing garments in a wooden wash barrel and hanging them on a clothesline. One headline read, “Give the Girls a Chance to Be Good Natured,” advising that washing early in the morning eliminated tired backs and tattered nerves and ensured pleasant Mondays. 3 In 1903, Fairbanks & Co. decided to give white women a rest from household chores and launched its national Gold Dust Twins campaign under the slogan “Let the Gold Dust Twins Do Your Work.” The face of the campaign was Goldie and Dustie—dark skinned, subservient minstrel characters who set white America at ease.

E.W. Kemble, staff artist for the Chicago Daily Graphic, created the commercial twins. Lore has it that 10-year-old David Henry Snipe and Thomas (no age or last name recorded) served as models for the rendering. 4 The young black males may have posed for the artist, but even they may not have recognized themselves in the final advertisements. Kemble depicted Snipe and Thomas as skirt-wearing, earring adorned, bald-headed genderless children, gleefully offering to clean floors, dishes, and more for the white woman of the house.

From their first appearance in the Atlanta Constitution in 1903, the twins were frolicking and scouring. The image was of one child assuming a wheelbarrow pose, hands on scrub brushes, the other held its sibling’s feet. The slogan “Let the Gold Dust Twins do your work” appeared above the twins. 5 Beneath the twins hung the tagline “Don’t break your back scrubbing your floors—there’s a better way.” Two days later, an advertisement, “Scrubbing floors is play for the Gold Dust Twins,” featured care-free twins, one sibling giggling while sitting on a scrub brush and holding the reins of a harness around the other who cheerfully pulled him along. 6

In April 1906, Atlanta got more than the advertisements; it got the southeastern headquarters of N.K. Fairbanks. According to Fairbanks officers, Atlanta was the natural choice for the branch, as it was “known everywhere as the most energetic and pushing city in Dixie.” 7 The Atlanta Constitution praised N.K. Fairbanks, noting, “These products have done much to make the world a better place to live in according to the cleanliness next to godliness theory as the quaint little Gold Dust Twins have attested in so many places.” 8

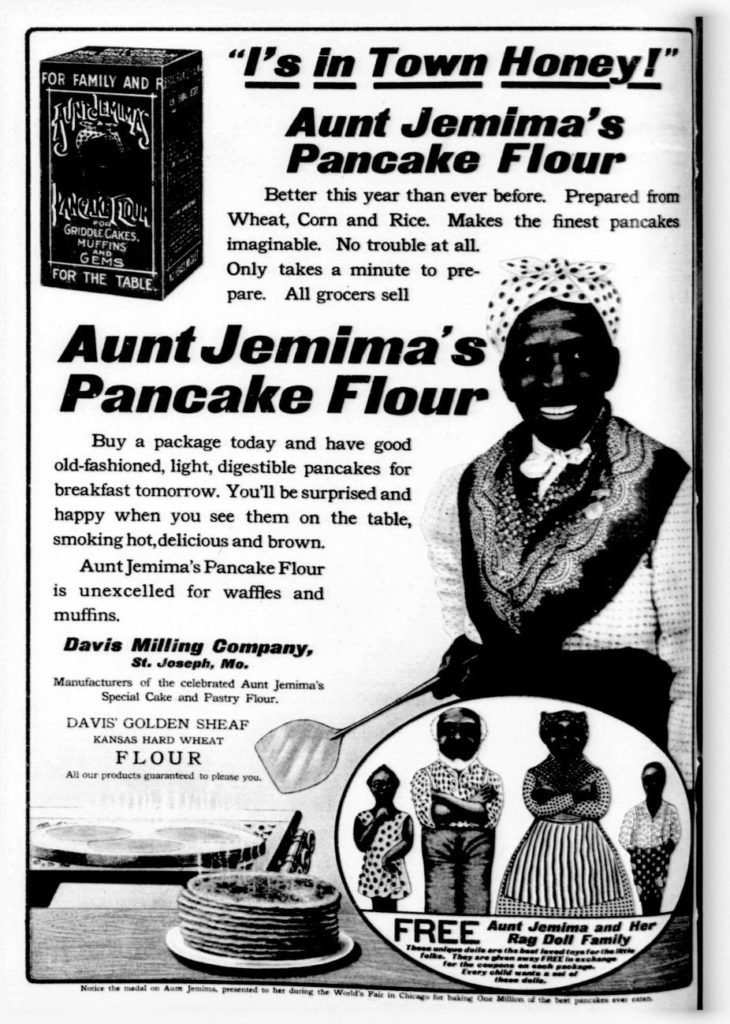

White America found solace in its docile Negro. By the turn of the 20th century, many were reminiscing about former slaves—faithful colored “aunties,” “uncles,” and “mammies”—who cared for them and showered them with love and gentle correction. As scholars of the U.S. South have shown, the region’s culture still waxed nostalgic about the Old South. Novels, plays and films cast African Americans as trustworthy, harmless, happy servants. 9 White consumers embraced Goldie and Dustie. Their sunny dispositions and willingness to work made white housewives feel secure. Such images allowed them to bask in a memory of a fabled South where the Negro was content, inferior, and eager to serve.

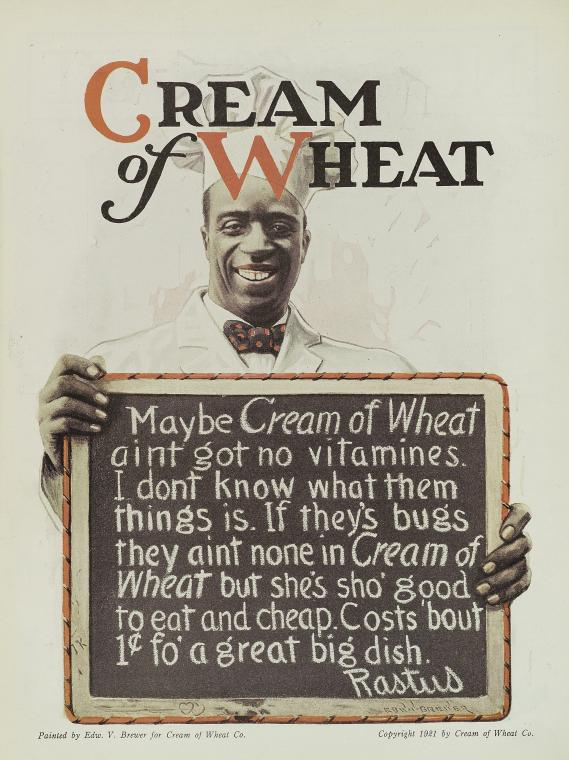

The Gold Dust Twins were not alone in assuaging white America and selling consumer products. The buxom, good-natured Aunt Jemima served up self-rising cakes so white consumers would not have to. A grinning chef Rastus confessed that when it came to vitamins, “I don’t know what them things is,” but promised, “If they’s bugs, they ain’t none in Cream of Wheat.” A dependable Aunt Jemima, a comical chef Rastus, and the sprightly twins were just what white consumers wanted and needed. As Marilyn Kern-Foxworth explains, advertisers promoted the belief that if it were “domestic work or menial labor, blacks could do it best . . . bake it, shake it, and make it best,” and used negative stereotypes to “sell everything from cigarettes to cereals.” 10

Eager to work, the Gold Dust Twins tidied everything. They were pictured sitting atop scrub brushes, balancing milk bottles while sprucing. They plucked a frying pan as if it were a banjo, and carried boxes of Gold Dust Washing Powder on their heads. They strapped brushes to their hands and feet and turned cartwheels and scoured away. The twins stacked laundry, washed dishes, shined mirrors, even cleaned windows of the White House. And the twins were always looking for work. One 1908 Atlanta Constitution advertisement assured that the Gold Dust Twins were “ready to lift the biggest burden of household labor from your shoulders and shift it to their own. When it comes to cleaning of any kind, they are the most willing and tireless little busybodies you ever knew.” 11 They answered white homemakers’ common complaints about black maids. “They work without wage and demand—no Thursday afternoons out.” 12 As compliant happy help, the Gold Dust Twins embodied white America’s desire to return to a mythical past. And the myth sold well in stores and in popular culture.

From the Box to the Stage

As the twins grew in popularity, their version of the South’s mythical past circulated in new form. In addition to adding the Gold Dust Twins to their pantry and shelves, white Atlantans applied black make-up to become them. According to the Atlanta Constitution, Mr. Jack Whitman and Mr. Newman dressed as the Gold Dust Twins at the 1904 Purim masquerade at the Progressive Club in Macon. They did not win first prize but were lauded for their costumes. 13 In Atlanta, two women entertained at the Ponce De Leon Cassion, becoming black-faced twins before audiences’ eyes. As the Atlanta Constitution reported, “Misses Foster and Byron will first appear in evening dress and then for a joke, determine to make up as the Gold Dust Twins and they ‘black up’ on the stage and make the change in costume so rapidly that the transformation is almost mystic.” 14

Whites continued to delight in black-face performances of the Gold Dust Twins. In 1908, the well-known actresses, the Nicol Sisters performed their rendition of the Gold Dust Twins at the Atlanta Orpheum. They were the “hit of the week,” declared the Atlanta Constitution, and “in a class all by themselves when it comes to taking off the dialect and the manners of the belles of Darktown.” 15 Several years later, Gold Dust Twins impersonators amused the Daughters of the Confederacy at a fundraiser in Decatur, Georgia, for the “benefit of the monument to commemorate the Battle of Shiloh.” 16 Indeed, the twins were everywhere. On February 20, 1912, two cadets of the prestigious Marist School made up in dark face for a minstrel show at Marist Hall. 17 In the fall of 1914, the twins arrived to delight children at a Halloween party at a local Presbyterian Sunday School. 18 The following year, 300 Georgia Tech students made headlines as they startled and entertained Atlantans with a parade “representing everything from a Jitney Bus to War Bride.” The procession caught traffic cops off guard “who reportedly gave in to laugh at impersonations of Charlie Chaplin, ‘Gold Dust Twins,’ 15 or 20, pseudo chorus girls and more.” 19 Amidst Atlanta’s white community —from its private clubs to its universities—the Gold Dust Twins continued to popularize the notions that blacks were meant—and glad—to serve.

What blacks thought of negative images of their race to sell products was of little concern to Fairbanks & Co. or the advertisements’ white audience. Undoubtedly African Americans in the early 20th century must have felt something when seeing themselves grinning, cooking, and cleaning for whites. Blacks learned to keep quiet, to bear shame, to laugh at what wasn’t funny in the presence of white employers, just as they had on the plantation in the presence of slaveholders. Indeed, as historian Grace Hale notes, for blacks facing a rising tide of discriminatory laws and lingering racial violence, the racist caricatures in advertising must have seemed relatively tame. 20

Advertisements Change

With the marketing genius of Fairbanks & Co., the twins’ popularity soared. In April 1909, Fairbanks distributed 40,000 packages of the Gold Dust Washing Powder in homes free-of-charge. As a result, according to the Atlanta Constitution, “the Nubians in abbreviated costumes is better known than the manufacturers. . .” 21 Yet, despite the enormous popularity of the Gold Dust Twins, one month later Fairbanks changed the advertisement. The ever-popular twins, once the central attraction of the campaign, were relegated to 1/8th of the printed advertisement space and had disappeared from Atlanta’s major newspaper by 1913.

Although no longer a part of the print advertisement, Goldie and Dustie remained embedded in American culture. The Gold Dust Twins radio program aired in 1929, and blackface impersonators tickled audiences into the 1930s and ’40s. Goldie and Dustie, however, could not withstand the tumultuous climate brought on by the struggle for civil rights. After sixty years the twins came to be viewed as “archaic, racist stereotypes. . .quickly turning from an asset to a liability.” 22 Yielding to change and product competition, the brand folded in the mid 1950s. 23

An Uncertain Future

Pinpointing when the Gold Dust Washing Powder advertisement was painted on the Auburn Avenue building is difficult. Since 1920, African American commercial enterprises from grocery stores, to a restaurant, to a drug store, stood on that location, although at times the structure was vacant. When Herndon purchased the lot from the New York Mortgage and Trust Company, he perhaps became the first African American to own the property. Why he elected not to whitewash the advertisement remains unknown. However, erecting the adjacent Herndon Building served the same purpose—blocking the subservient Gold Dust Twins from view. When the Herndon Building went up, no doubt some African Americans breathed a sigh of relief. Harvard University trained economist Paul K. Edwards reported in his 1932 study, African Americans “especially disliked the Gold Dust Twins, calling those original twins . . . disgusting, a caricature and ridiculous and not a true picture of Negroes.” 24

Still today, many find the mural offensive. Janis Perkins, managing partner of the Odd Fellows Building, does not appreciate the mural’s presence on Auburn Avenue. “Whose history is it telling? Who wants it there?” she asks, suggesting that the caricatures tell more about white privilege to define blacks than about black achievement and self-identity. Unpersuaded of the mural’s value, Perkins continues, “If it’s historic, if it’s that important, take it down, brick by brick and put it in a museum. It doesn’t belong on Auburn Avenue,” Perkins concludes. “It doesn’t belong here.”

Despite their controversy, the twins remain unscathed. While young artists have tagged the building with their signatures, they haven’t touched the twins, abiding by the code that one should not deface another’s artwork. Unlike the uproar in 2012 over murals by Living Walls that offended some residents of South Atlanta, no one has painted over the Gold Dust Twins advertisement or demanded that it come down. To preservationists, the advertisement may be important. The Gold Dust Washing Powder advertisement is a rare “ghost mural,” perhaps an added incentive to restore and preserve it.

Time is running out for Goldie and Dustie. The building at 229 Auburn Avenue is slated for demolition, and the image is fading fast. Perhaps the advertisement can be saved, brick by brick as Perkins suggested. In April 2015, Atlanta City Councilmember Michael Julian Bond introduced a resolution to convene a study group of preservationists and historians to determine “an appropriate means of preserving the advertisement.” 25 The resolution was referred to the community development/human resources committee without objection, perhaps a nod from city leaders that this piece of history might be worth keeping.

Like Goldie and Dustie, the past rarely remains hidden. It inevitably shapes our present. History along Auburn Avenue—from the Gold Dust Twins to the Martin Luther King, Jr., National Historic Site—attests to black America’s resolve. When the Gold Dust Twins advertisement went up, African Americans responded by building the Odd Fellows complex, opening businesses, training a professional class, and putting their stamp on the arts. What to do with the Gold Dust Twins? Bring them to the forefront. Let us have conversations about race and how we let it define others. A new generation must learn of the struggles of African Americans to overcome negative stereotypes. Perhaps then the ever-busy, dutiful twins can finally take their rest.

Citation: Thomas, Velma Maia. “Your Advertisement Troubles Me: Atlanta’s Gold Dust Twins.” Atlanta Studies. July 02, 2015. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20150702.

Notes

- Vacant for a number of years, the building was purchased in 2013 by the Butler Street Community Development Corporation. The structure, already in a weakened state, was heavily damaged by the 2008 tornado.[↩]

- “Fairbank (N. K.) & Co.,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, accessed March 23, 2014, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/2657.html.[↩]

- The Atlanta Constitution, June 2, 1892, 7.[↩]

- “Gold Dust Twins Washing Powder Wood Plaque Ad,” Cushcity.com, accessed March 23, 2014, http://www.cushcity.com/books/colhpp0017.htm.[↩]

- The Atlanta Constitution, September 5, 1903, 7.[↩]

- The Atlanta Constitution, September 7, 1903, 5.[↩]

- “Atlanta Gets Headquarters: W.K. Fairbanks to Establish Offices Here,” The Atlanta Constitution, April 22, 1906, A3.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- For a full discussion of black stereotypes in film, see Donald Bogle, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, & Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Film (New York: Bloomsbury, 2001).[↩]

- Marilyn Kern-Foxworth, Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, and Rastus Blacks in Advertising, Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow (Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group), 41.[↩]

- The Atlanta Constitution, September 15, 1908, 5.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- “Social Life in Macon,” The Atlanta Constitution, March 6, 1904, B3.[↩]

- “The Theaters,” The Atlanta Constitution, June 5, 1904, B9.[↩]

- “The Theaters,” The Atlanta Constitution, March 19, 1908, 15.[↩]

- “Entertainment at Decatur,” The Atlanta Constitution, May 21, 1911, E12.[↩]

- “Minstrel Show at Marist Hall,” The Atlanta Constitution, February 20, 1912, 6.[↩]

- “Society,” The Atlanta Constitution, November 8, 1914, B8.[↩]

- “In Weird Attire Students of Tech Startle Atlanta,” The Atlanta Constitution, June 8, 1915, 1.[↩]

- Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940 (New York: Vintage Books, 1999), 182. Hale submits that black consumers saw products that used negative stereotypes to appeal to whites, but they had greater issues of concern.[↩]

- “Giving Away Packages of ‘Gold Dust Twins,'” The Atlanta Constitution, April 14, 1909, 3.[↩]

- “Package Obituaries,” History of Product Packaging, accessed April 19, 2015, http://www.hagley.org/online_exhibits/packaging/casualty.html.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Hale, Making Whiteness, 181.[↩]

- City of Atlanta, Georgia, Resolution 15-R-3432, April 20, 2015, accessed May 16, 2015, “Creation of Gold Dust Trail Committee,” http://atlantacityga.iqm2.com/Citizens/Detail_LegiFile.aspx?Frame=&MeetingID=1509&MediaPosition=&ID=6669&CssClass=.[↩]