Months before Atlanta’s public schools desegregated, someone bombed an all-Black school on the city’s Westside. On the 60th anniversary of that incident, Max Blau and Todd Michney revisit the forces that led to the attack and reflect on its legacy.

Early one freezing morning in December 1960, two weeks before Christmas, a bomb flew through the sky toward the red-brick walls of the English Avenue School. The explosive bounced off the building back toward Pelham Street. A bright flash followed. A deafening boom came next. Chunks of pavement hurtled airborne, landing on the roofs of nearby homes. English Avenue residents, roused from their sleep, peered outside their windows. Few stepped outside into the darkness before dawn.1

Greg Walker woke up the next morning unaware of what had happened. He got ready for school like any other Monday, eager to sit at his desk near the front of his first-grade classroom. When he headed for the door, his mother said he wasn’t going to school. He asked why, but she wouldn’t say. He pressed again. No answer. His father eventually broke the news: Someone had bombed his school. They wouldn’t let him go see it at first. But Walker pestered his mother for hours until she finally relented.2

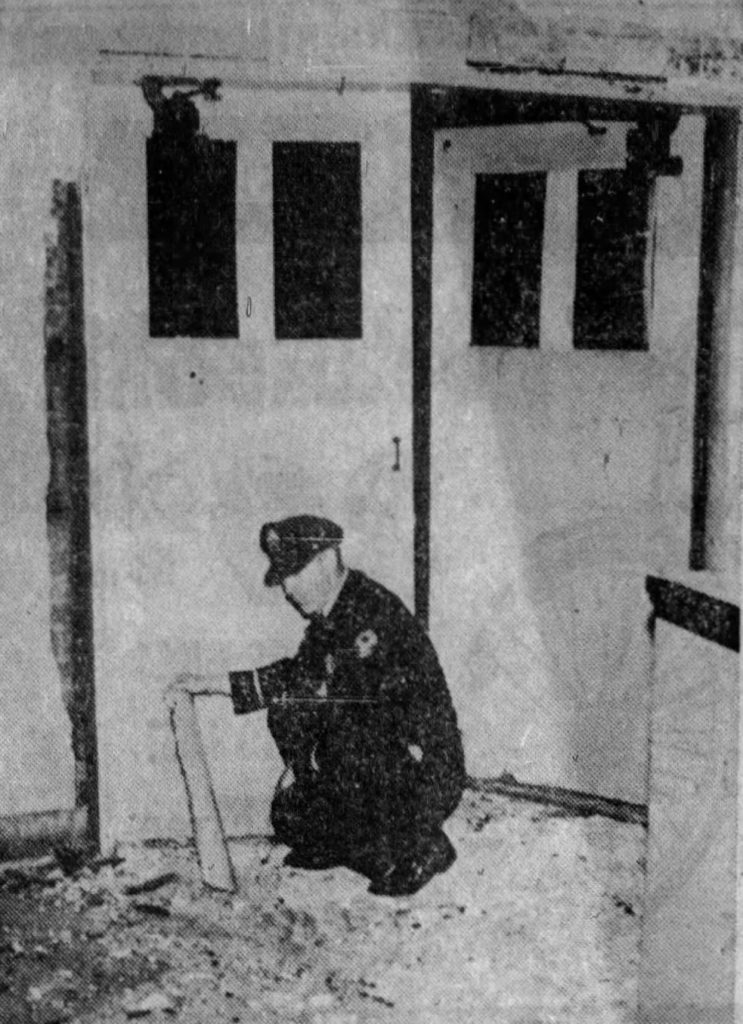

After he and his older sister walked a few blocks from their home on Ashby Street, Walker could see the damage done. Doors had flown off their hinges. Windows had shattered. Blinds had tattered. The holiday cards colored by his classmates no longer hung on the wall. “I was very angry about it,” Greg later recalled. “I cried.”3

Walker considered his classroom a sanctuary, in large part because of his teacher, Ms. Anna Ruth Jones. She was not only Walker’s teacher, but an advocate who called for equality in learning opportunities, textbooks, and funding for schools attended by Black students. She even helped organize the B.S. Burch Honor Society, named after a principal of the English Avenue School. When students like Walker made the honor roll, they wore suits to school on Fridays, and donned red beanie caps with the letters B.S.B. on it.4

“People would be sitting on their porch, watching kids go to school, would call kids with the beanies—Come here, baby! come here!— and give them a dime or a quarter,” he recalled. “There was a sense of pride.”5

Standing behind crime scene tape, Walker felt pain more than pride that fateful Monday afternoon. Detectives stepped around a wide crater in the ground, looking for clues that could lead to the people responsible for a bombing that would soon make national headlines. But in ways spoken and unspoken, the response that followed reflected the broader division America faced during the middle of the Civil Rights Movement.

The English Avenue School bombing marked the convergence of two dark legacies. The bombing drew attention to the massive resistance faced by southern school systems leading up to desegregation in the years after the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board ruling in 1954. And it exemplified a now-little remembered era of racial terror that came in the form of small-scale attacks that sought to strike fear in Black communities.

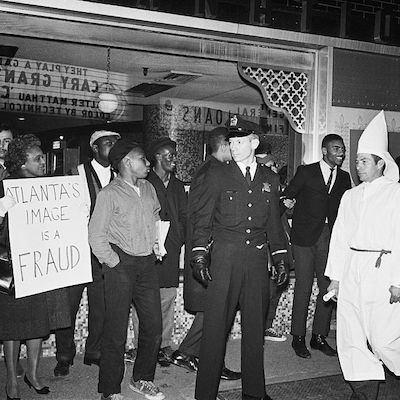

As columnists called on civic leaders to take more decisive action to advance racial equality, leaders like Atlanta Mayor William B. Hartsfield downplayed the presence of hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan inside the city proper,6 a posture that aimed to promote the reputation Atlanta was building as the “city too busy to hate.” But in the face of that hate, and the absence of a stronger response, students like Walker would be forced to learn lessons of resiliency and self-determination at an early age.

Struggles over Desegregation

The 1960 bombing expressed white resentment toward the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta and the nation as a whole. The city’s racially-segregated school system, just months away from integration, exemplified those ongoing changes.

Prior to 1950, Atlanta public school officials had designated the English Avenue School only for use by white children. Built in 1911, the elementary school with its communal gardens had served as a site for neighborhood meetings and as a polling place. White residents had even succeeded in getting it renamed for its beloved first principal, Lula L. Kingsbery.7 A handful of African-American families resided in the vicinity at the time the school was built, and attended a Black church just blocks away. But as the English Avenue neighborhood’s white population swelled during the 1920s, necessitating additions to accommodate more students, Black families were also moving into the area from the historic neighborhood of Vine City to the south. This demographic trend accelerated dramatically during the 1940s, as the blocks adjacent to the school went from all-white to overwhelmingly Black.8

Under the segregated schools policy of the time, African-American students had to walk more than a mile to attend half-days at the overcrowded and dilapidated Gray Street Elementary School. In 1948, Black parents in the neighborhood petitioned Atlanta’s school board to change the English Avenue School’s racial designation, considering that white enrollment there had dwindled drastically.9 Besides the neighborhood’s changing demographics, a 1950 federal lawsuit by the NAACP helped convince school officials to make the switch.10

Kingsbery’s name was taken off the front of the school. Following that change, hundreds of white residents gathered in angry protest on at least two occasions, as well as lodged formal complaints opposing the change. As years passed, white residents still living in the vicinity—most of them in “Bellwood,” a neighborhood north of Bankhead Highway (today’s Donald Lee Hollowell Parkway) which served as a racial boundary amid an ongoing demographic transition—remained bitter about the decision. “Not one city official, not one member of the school board was on hand to talk to the families, to explain what was happening, or to try to clarify the situation,” a white former principal would later recall.11

A decade passed without violence at the school. But in late 1960, the bombing happened amid escalating civil rights protest and impending school desegregation across the South. A class-action lawsuit by Black parents had resulted in a 1959 U.S. District Court decision that Atlanta’s school system was in breach of Brown. This development prompted Mayor Hartsfield to support a “local option” plan that delayed full integration by creating hurdles for Black students to transfer schools and allowed desegregation to proceed at a slow pace. While white Atlantans of the same mind as Hartsfield coalesced into Help Our Public Education Inc., others formed the Metropolitan Association for Segregated Education and launched anti-desegregation rallies after a 1960 state commission found in favor of a token, local option plan. In the month before the bombing, New Orleans witnessed ugly scenes of opposition to the desegregation of its school system, as federal marshals had to be deployed to protect elementary school children from enraged white mobs.12 The English Avenue bombing raised the possibility that such ugly scenes might also play out in Atlanta.

Hatred Reaps Its Harvest

Phone calls flooded into Atlanta’s police precincts about the damage done to windows, walls, and roofs in the hours after the bombing. Residents believed that Ms. Jones’s classroom was targeted because of her advocacy for students like Walker to get new textbooks instead of outdated ones discarded by white schools. Investigations suggested another theory: Local organizers had held a sunrise prayer service the day before at the nearby Herndon Stadium, followed by a march to downtown, to show solidarity with college students who recently participated in sit-ins, which had drawn counter-protests from the Ku Klux Klan. The march was part of a months-long protest campaign seeking the desegregation of downtown stores, led by Black students and which saw the arrest of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that October. Detectives asked nearby residents about what they saw the night before, and fanned out looking for past instigators of racial violence, and called in the Federal Bureau of Investigation for assistance.13

“It was the work of a fanatic,” one detective told the Atlanta Constitution. “Of that we are sure.”14

The following day, Atlanta Constitution editor Ralph McGill, who the year before won a Pulitzer Prize for his anti-segregationist columns, published a story titled “Hatred Reaps Its Harvest.” Describing images of “colored Christmas drawings of children lovingly done” scattered on a classroom floor, McGill connected the violence to the inaction of Atlanta’s civic leaders who chose not to take a strong stance against hate and intolerance. In doing so, he characterized the moment as one in which “Southern leadership is put to the test.”15 As he wrote:

Men and women in high places who organize groups to resist court orders, those who urge pledges of never surrendering, and who encourage those of the Klan mentality, did not toss the explosive at the school. But in a very real sense, their hands were there just the same.

Even as national outlets like the New York Times and Jet covered the attack, Atlanta’s civic leaders did not fully live up to McGill’s call. Mayor Hartsfield urged Atlantans to speak out against racism, hoping to avoid a scenario in which “a few little loud-mouthed racial demagogues will be mistaken for the voice of Atlanta.” As he explained:

Most of these racial demonstrators come from outside our city limits. They are what we call the ‘outhouse crowd.’ . . . Practically all of the rabble-rousing, cross-burning, sheet-flapping and dynamiting is done by people who do not live inside the limits of Atlanta.

In other words, Hartsfield worried that rural white people would tarnish the city’s “good reputation for race relations”—a nod to the “Atlanta Way,” the coalition of white and black business leaders who worked together to uphold an image of the city as a supposed bastion of peace and tolerance.16

More officials condemned the bombing, but did little else to act in response to the attack. That week, Atlanta’s public school board held its monthly meeting, where its members quickly blamed the attack on isolated actors. A.C. Latimer, the school board president, called the bombing the work of a “diseased mind” who had created a “blot on Atlanta’s fine reputation.” The lone Black school board member, Dr. Rufus Clement, president of Atlanta University, noted that no racial trouble had otherwise occurred at the school in the nine years since the switch from white to Black use.17

“I’m certain that all law-abiding citizens abhor this kind of conduct on the part of any citizen,” Clement said at the meeting.18

The Era of Hidden Violence

The conciliatory tone of Atlanta’s civic leaders and elected officials had long failed to stop racially-motivated bombings. In the thirteen years leading up to the 1960 school bombing, there were no less than 19 such attacks within Atlanta’s city limits targeting African-American families who moved into formerly all-white neighborhoods on the city’s south and west sides (see timeline). That April, someone dynamited a house in Adamsville to intimidate a family who had purchased it, after a flurry of transactions that signaled the start of a “blockbusting” campaign to pressure white owners to put their homes up for sale. Just months before the English Avenue School was targeted, an arsonist firebombed a Black-owned car-for-hire company on Bankhead Highway, while dynamite bombs were detonated on two African-American homeowners’ front lawns in Grove Park.19

No attack gained more notoriety than the 1958 bombing of the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, Atlanta’s most prominent synagogue better known as “The Temple.” Rabbi Jacob Rothschild, a longstanding civil rights supporter and close friend of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., had spoken out about the need for reconciliation in the wake of the 1957 Little Rock school integration crisis. Upon inspecting the Temple’s damage, Mayor Hartsfield had blamed segregationists, opining, “whether they like it or not, every political rabble-rouser is the godfather of these cross burners and dynamiters who sneak about in the dark and give a bad name to the South.”20

Like Atlanta, the rest of the South saw its share of race-related bombings in the two decades after World War II. Birmingham had already earned its nickname “Bombingham” before the 1963 white supremacist attack on the 16th Street Baptist Church that killed four young Black girls. In cities like Dallas, white people systematically used bombing and arson in attempting to maintain the residential color line.21

While some southern states had begun regulating access to dynamite more stringently during the 1950s, others like Louisiana and Virginia still had no restrictions on sales; South Carolina and Alabama merely required explosives dealers to keep records of purchasers. Georgia also had a law requiring such records to be kept, although it was rarely enforced before the 1958 Temple bombing.22 Insufficient regulations concerning the purchase and possession of dynamite, along with the lax enforcement of existing laws, created opportunities for bombers to further terrorize Black communities like English Avenue.

Racially-motivated bombing attacks transpired in the North as well. While attacks were prevalent in cities from Philadelphia to Los Angeles, Chicago was the undisputed hotbed of violent white resistance.23 Historian Arnold Hirsch has calculated that between 1945 and 1950 a bombing or arson was perpetrated there once every twenty days on average. On several occasions, thousands of angry whites thronged the streets to oppose African-Americans moving into previously-segregated public housing complexes, private apartments, and homes.24 Hirsch strikingly described the period in Chicago from 1945-1960 as “an era of hidden violence” characterized by “chronic urban guerrilla warfare.”25

Whether in the North or South, the violence had common motivations: competition for housing before suburbanization had gotten fully underway, and resentment at the civil rights gains that African-Americans were racking up, whether through Supreme Court rulings like Brown v. Board, or via coordinated protests like the 1955-1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott. Bombings and arson were tactics on a continuum that also frequently included harassment, property vandalization, and white attempts to buy back homes from Black purchasers after the fact.26

There were a variety of reasons why these bombings continued, and why they often went unsolved. Some city officials dismissed attacks as teenage pranks.27 White police officers did not always pursue full investigations due to their own prejudices against Black people; the violence in Chicago had remained “hidden,” Hirsch discovered, because public officials negotiated a press blackout intended to discourage copycat incidents.28

In Atlanta, Mayor Hartsfield did not hide from the violence, but sought to emphasize the “Atlanta Way” of racial cooperation in the name of civic progress. However, Hartsfield’s assertions belied the realities of racial animosity. The Ku Klux Klan not only had an active presence across Georgia at the time, it also manifested in the Atlanta metropolitan area despite Hartsfield’s claims. Fulton County granted two charters to new KKK chapters in the year leading up to the bombing; in the month prior to the incident the Klan had set up “coffee stands” at freeway stops outside the city, and held a rally at Stone Mountain where speakers called for public schools to be closed or burned rather than integrate. Hartsfield’s message did not stop KKK activity; the group would soon thereafter hold a rally in nearby Almond Park, and later screen the racist film The Birth of a Nation there.29 Nor did Hartsfield’s positive spin end the broader pattern of violence: three more Black-owned homes were bombed in the year that followed.30

“A Level of Fortitude”

By the time students returned from winter break in early 1961, the police investigation had stalled. While some English Avenue residents suspected the KKK,31 no one faced charges for the bombing. As the months passed, the eyes of the nation shifted elsewhere in the South. People followed seminal Georgia moments of the Civil Rights Movement from the divisive integration of the University of Georgia to the Freedom Rides.

Atlanta’s school board members also focused on the challenges ahead, including the desegregation of its system the following school year. To his credit, Hartsfield deployed a massive police presence when the Atlanta Public Schools rolled out their desegregation plan that Fall, thereby avoiding the shocking scenes that had beset New Orleans.32

However, school officials slowly eased into the era of integration for the 1961-62 school year, approving a plan that would have taken 12 years with negligible results if it had been fully carried out. Only ten Black students received approval for transfers to once-white schools that first year. Those students, along with their immediate successors, faced reactions from white teachers and students alike that ranged from frosty to openly hostile.33

The periodic bombings reminded some Black Atlantans of continuing opposition to their gains. Students like Greg Walker could not unsee the image of his classroom sanctuary turned into a crime scene. He carried ongoing lessons from Ms. Jones on topics such as segregation and hate wherever he went. In the years following the bombing, he helped integrate his local Boys Club, the youth organization that preceded the Boys and Girls Club of America. As he turned into an avid reader, he slowly came to believe that change could only come if he actively participated in politics. So he volunteered to register voters and work on Maynard Jackson’s 1973 campaign to become Atlanta’s first Black mayor. He then became a law enforcement officer and attended the FBI’s National Academy, working with an agency that could not solve the bombing of his school years earlier.34[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]“[The bombing] really brought about a level of fortitude in those that were fighting against segregation to fight even harder, to make sure and ensure that we was able to overcome those disparities that existed,” Walker recalls.35

On a warm Saturday morning in June 2019, Walker, now in his sixties, stood on Pelham Street near where the bomb had once exploded, destroying the Christmas drawings of his classmates.36 He spoke about how APS rebuilt the elementary school. But the forces of disinvestment, crime, and poverty beset English Avenue in the 1970s and 1980s. Not only did the last of the white residents leave the neighborhood, so did Black residents who moved up into the middle class; Walker himself had left the neighborhood in 1969.37

In 1995, APS officials closed down the English Avenue School due to low enrollment and the building sat vacant for nearly a quarter century. (Greater Vine City Opportunities Program, a nonprofit led by Georgia State Rep. “Able” Mable Thomas, purchased the building in 2009, and recently helped get the building added to the National Register of Historic Places. The current owner, Westside Development Partners, is now looking to repair and redevelop the property.) After pointing out his old classroom, where Ms. Jones once taught those early life lessons, Walker headed back toward his car. As he walked away, tears did not stream down his face, as they had decades earlier. Instead, he smiled, hopeful that he had made Ms. Jones proud.38

Additional research for this article was conducted by Georgia Tech students in Professor Michney’s Fall 2020 “Semester in the City” class, and Building Memories podcast intern Charles Cardot. Audio content prepared by Building Memories intern Amrithesh Paravath.

Cover Image Attribution: KKK Members and Civil Rights Protesters in Atlanta, January 1964. Bettmann Archive. Copyright Getty Images.

Fair Use Guidelines: The images are scans of newspaper pages, and the copyright for it is most likely held by either the publisher of the Miami Herald or the individual contributors who worked on the articles or images depicted. It is asserted that the use of these low-resolution images of newspaper pages in the non-profit academic journal Atlanta Studies Journal article “Terror in the City Too Busy to Hate: How the English Avenue School Bombing Challenged Atlanta’s Popular Myth of Racial Progress” qualify as a fair use of the images for the following reasons: The images are clippings of Miami Herald headlines and brief article sections directly related to the Atlanta Studies Journal article, thus illustrating the topic of and substantially improving the legitimacy of the ASJ article’s content. Because the images are small clippings, their use in ASJ’s article does not compete with the use of the copyright holder(s). The images are used in the ASJ article for scholarly and educational purposes and are not used for profit. Their use in the ASJ article does not decrease the value of the copyright to its holder(s).

Citation: Blau, Max and Todd Michney. “Terror in the City Too Busy to Hate: How the English Avenue School Bombing Challenged Atlanta’s Popular Myth of Racial Progress.” Atlanta Studies. December 12, 2020. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20201212.

Max Blau is an Atlanta-based journalist who writes narrative and investigative stories. A graduate of the University of Georgia’s narrative nonfiction M.F.A. program, his previous writings about Atlanta’s west side have appeared in Atlanta, The Bitter Southerner, Creative Loafing, CNN, and Politico magazine. Follow him on Twitter @MaxBlau, or send him an email at maxcblau@gmail.com.

Todd M. Michney is an Assistant Professor in the School of History and Sociology at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He is the author of Surrogate Suburbs: Black Upward Mobility and Neighborhood Change in Cleveland, 1900-1980 (University of North Carolina Press, 2017). Follow him on Twitter @ToddMichney, or email him at todd.michney@hsoc.gatech.edu.

Notes

- Keeler McCartney, “Detectives, FBI, Army Hunt Clues,” Atlanta Constitution, December 13, 1960; John Britton, “F.B.I., Army and Police Probing School Bombing,” Atlanta Daily World, December 13, 1960; Paul Delaney, “No New Leads in School Bombing,” Atlanta Daily World, December 14, 1960.[↩]

- Nedra Sims Fears, interview with Greg Walker, April 12, 2014, transcript included with English Avenue School National Register of Historic Places Application (June 2018), on file at Georgia Department of Natural Resources (Stockbridge, GA); Max Blau, interview with Greg Walker, June 2019.[↩]

- Blau interview with Walker; Fears interview with Walker; Delaney, “No New Leads”; “A Negro School Bombed in South,” New York Times, December 13, 1960; Keeler, “Detectives, FBI, Army”; Ralph McGill, “Hatred Reaps Its Harvest,” Atlanta Constitution, December 13, 1960.[↩]

- Blau interview with Walker; Chrissie Wayt, interview with Greg Walker, April 13, 2014, transcript included with National Register of Historic Places Application; Max Blau, interview with Vincent Jones, May 2019.[↩]

- Blau interview with Walker.[↩]

- “Dynamiters Hit Georgia Negro School,” Arizona Republic, December 13, 1960.[↩]

- National Register of Historic Places Application, 19-20, 28; Megan W. McDonald, “The House by the Side of the Road: A History of the Andrew P. Stewart Center,” M.A. thesis (Georgia State University, 2018), 15-16, 19-21.[↩]

- National Register of Historic Places Application, 22, 25-27, 29, 30; “Will Discuss Plans for English Avenue School Addition,” Atlanta Constitution, August 28, 1922; “English Avenue Plants Gardens on School Yard,” Atlanta Constitution, April 10, 1932; McDonald, “House by the Side of the Road,” 39-42, 47-50. For a white former resident’s firsthand recollection concerning the area’s demographic transition, see Clifford Kuhn, interview with Alec Dennis, June 21, 1979, Living Atlanta Oral History Recordings, Atlanta History Center, available online at https://album.atlantahistorycenter.com/digital/collection/LAohr/id/25/rec/2.[↩]

- McDonald, “House by the Side of the Road,” 42-47; National Register of Historic Places Application, 30-31; C. Lamar Weaver, “School Facilities Inadequate,” Atlanta Daily World, September 12, 1948; C. Lamar Weaver, “Hazards and Neglect Handicap to Students,” Atlanta Daily World, September 12, 1948; “Board of Education Turns White School Over to Negroes,” Atlanta Daily World, June 15, 1950; Herman Hancock, “Kingsberry Will Become Negro School in Fall,” Atlanta Constitution, July 12, 1950.[↩]

- Kevin Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 134. On other efforts around this time to avoid desegregation by taking “separate but equal” more seriously, see Steven Moffson, “Equalization Schools in Georgia’s African American Communities, 1951-1970,” Historic Preservation Division, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, September 20, 2010.[↩]

- National Register of Historic Places Application, 31-32; Dick Hodges, “School Shift to Negro Use Stirs Whites,” Atlanta Constitution, July 7, 1950; “Board of Education Stands Pat on Kingsberry Decision,” Atlanta Daily World, July 12, 1950; “Shifted Pupils’ Fare from Homes Sought,” Atlanta Constitution, September 12, 1950; Kruse, White Flight, 148.[↩]

- Kruse, White Flight, 135-44, 146-47. For the larger context, see Jeff Roche, Restructured Resistance: The Sibley Commission and the Politics of Desegregation in Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010).[↩]

- Britton, “F.B.I., Army and Police”; Blau interview with Walker; Keeler, “Detectives, FBI, Army”; “Vacant Negro School Is Bombed in Atlanta,” Anniston Star [Anniston, AL], December 13, 1960; “Negro School Bombed in South.” On the 1960 Atlanta sit-in campaign, see especially Tomiko Brown-Nagin, Courage to Dissent: Atlanta and the Long History of the Civil Rights Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 133-74.[↩]

- McCartney, “Detectives, FBI, Army.”[↩]

- McGill, “Hatred Reaps Its Harvest.”[↩]

- “Negro School Bombed in South”; “Bombing of Atlanta Negro School Triggers Protests,” Jet 19, no. 10 (December 29, 1960), 22; “City, State Authorities Outraged,” Atlanta Constitution, December 13, 1960.[↩]

- Joel W. Smith, “School Bombing Big Shock to Atlanta Board of Education,” Atlanta Daily World, December 13, 1960; “City, State Authorities Outraged.”[↩]

- “City, State Authorities Outraged.”[↩]

- Warren Bosworth, “New Home of Negroes Is Bombed,” Atlanta Constitution, April 14, 1960; Margaret Shannon, “Areas in Transition,” Atlanta Constitution, April 17, 1960; “3 Bottle Bombs Shake Negro Office Here,” Atlanta Constitution, September 17, 1960; “Blast Rips into Lawn of Negro Home,” Atlanta Constitution, October 22, 1960; “Blast Rocks 4 Homes,” Atlanta Constitution, November 19, 1960.[↩]

- “Rabble-Rousers Share the Blame, Mayor Says,” Atlanta Constitution, October 13, 1958. On the incident, see Melissa Fay Greene, The Temple Bombing (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 1996).[↩]

- On Birmingham, see Glenn T. Eskew, But for Birmingham: The Local and National Movements in the Civil Rights Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 53-83; and Charles E. Connerly, “The Most Segregated City in America”: City Planning and Civil Rights in Birmingham, 1920-1980 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005). On Dallas, see Robert B. Fairbanks, For the City as a Whole: Planning, Politics, and the Public Interest in Dallas, Texas 1900-1965 (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1998); and William H. Wilson, Hamilton Park: A Planned Black Community in Dallas (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998).[↩]

- “Dixie States Stiffen Laws on Explosives,” Atlanta Constitution, October 25, 1958.[↩]

- Arnold R. Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago, 1940-1960 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983). On violent white homeowner resistance in other northern and western cities, see especially Steven Grant Meyer, As Long as They Don’t Live Next Door: Segregation and Racial Conflict in American Neighborhoods (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000); Thomas J. Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), 231-58; James Wolfinger, Philadelphia Divided: Race and Politics in the City of Brotherly Love (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 85-112; Josh Sides, L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 102-27; and Kevin Fox Gotham, Race, Real Estate and Uneven Development: The Kansas City Experience, 1900-2000 (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002), 63-70.[↩]

- Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto, 41, 52, 53-54. For a particularly disturbing incident, see Arnold R. Hirsch, “Massive Resistance in the Urban North: Trumbull Park, Chicago, 1953-1966,” Journal of American History 82 (September 1995): 522-50.[↩]

- Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto, xi, 41.[↩]

- On a buyback campaign in Atlanta’s white working-class Adamsville neighborhood, see Kruse, White Flight, 84-85.[↩]

- In contrast to the FBI, local police focused attention on teenagers in the English Avenue School case; see Keeler McCartney, “Police Find Teen Hoard of Dynamite,” Atlanta Constitution, December 31, 1960.[↩]

- Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto, 60-63.[↩]

- “Klan Group Granted a Charter Here,” Atlanta Constitution, December 10, 1959; Marion Gaines, “Women-Only Klan Chartered in Fulton,” Atlanta Constitution, July 9, 1960; Bill Shipp, “Klan Offers Free Coffee, Literature at Roadsides,” Atlanta Constitution, November 25, 1960; Charles Moore, “Klan Hails Call for Closings,” Atlanta Constitution, December 1, 1960; “Police Threatened by Klan Crowd,” Atlanta Constitution, September 5, 1961; “800 Attend Klan Rally, View Movie,” Atlanta Constitution, July 5, 1962.[↩]

- “Atlantan Escapes in Home Blast,” Atlanta Constitution, May 26, 1961; “Blast Jolts Negro Section,” Atlanta Constitution, July 5, 1961; Keeler McCartney, “Blast Rocks 2 Homes of Negroes,” Atlanta Constitution, July 28, 1961.[↩]

- Maya Harrell and Annie Tran interview with Greg Walker, November 1, 2020.[↩]

- Kruse, White Flight, 152-55.[↩]

- Raleigh Bryans, “10 Negroes Approved for 4 White Schools,” Atlanta Constitution, June 4, 1961; Kruse, White Flight, 151, 156-60.[↩]

- Fears interview with Walker; Blau interview with Walker.[↩]

- Harrell and Tran interview with Walker.[↩]

- Blau interview with Walker. The interview was conducted on site at the school.[↩]

- Ibid.; Max Blau, “The Redemptive Love of Chiliquila Ogletree,” The Bitter Southerner, April 2018; Fears interview with Walker; Harrell and Tran interview with Walker.[↩]

- National Register of Historic Places Application, 36-37; Dyana Bagby, “Developer Revives Plans to Restore Atlanta’s Historic English Avenue School as Community Center,” Atlanta Business Chronicle, October 7, 2020; Blau interview with Walker.[↩]