For one hundred years, sociologists have embraced the precept that University of Chicago sociologists Robert Park and Ernest Burgess founded the first American school of sociology – the Chicago school – circa 1915.

Neophytes are taught that prior to the urban studies of the Chicago school, American sociology was mostly idealist social philosophy absent systematic empirical methods for investigating the human condition. So the doctrine goes: it was not until researchers of the 1920s and 1930s began their steady churn of empirical studies on urbanization and social life in Chicago, that sociology became a “real science.”1 In The First American School of Sociology: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Atlanta Sociological Laboratory, Earl Wright II pushes back against this orthodoxy on the discipline’s origins to argue that the social laboratory at Atlanta University preceded Chicago as the first school of collective sociological research based on scientific inquiry. Marshaling as manifest evidence the rich body of research produced in Atlanta from 1896 to 1917, Wright’s intervention is convincing and long overdue.

Earl Wright II, Professor of Sociology at the University of Cincinnati, has been publishing scholarly articles about Du Bois, the Atlanta school, and Black Sociology for fifteen years.2 The First American School is his first book-length treatment.

The book’s central argument portends a radical game change for the sociological canon, not just because it resets the timeline earlier than previously thought, nor simply because it relocates the birthplace of the field from the urban North to urban South, but also because it places a coterie of black researchers from an under-resourced black university in the Jim Crow South at the beginning and center of scientific sociology’s development. Wright’s case rests on several traceable assertions that demonstrate the Atlanta social scientists’ strategic and prolific research agenda, their methodological dexterity, and their paradigm-shifting contributions to race theory.

Under the leadership of W. E. B. Du Bois, the Atlanta Sociological Laboratory published annual studies of black life that resulted in a twenty-volume monograph series: The Atlanta University Study of the Negro Problems. Each component study explored a specific subject in depth (e.g.: “Mortality among Negroes in Cities,” “The Negro Church,” “The Negro Artisan”) and many of the later studies revisit the subjects of earlier studies. As Wright details, these investigations employed sophisticated methods of original data collection, including the use of “insider citizen researchers” (78) from local black communities across the nation. Atlanta researchers also invented a process of method triangulation to validate metrics and findings from diverse data sources. Crucially, the data output and analyses of the Atlanta school challenged prevailing views of the biological inferiority of black people by demonstrating the reproduction of racial inequalities through social patterns and structures.

The centerpiece of Wright’s book and its primary strength are his concise synopses of these oft-overlooked publications. Wright nimbly details the substance, methods, data sources, general results, and recommendations of each study, while culling the historical and institutional factors informing their scope and limitations. The catalog approach may not appeal to all readers, but its efficacy is the panoramic view it provides of these early studies as a cohesive and incremental body of work. This global strategy wears thin, however, in the final interpretive chapter, where Wright refers readers to his previous articles for further reading on contextual information not detailed in the book. The practicality of the maneuver is evident. Yet, with his sustained focus on Du Bois within the book, Wright rushes too hastily past his own groundbreaking articles discussing other members of the Atlanta Laboratory – such as Monroe Nathan Work and Lucy Craft Laney – and key participants of the annual Atlanta Conferences – including Mary Church Terrell, Kelly Miller, and Walter Wilcox. Readers unfamiliar with Wright’s previous work are invited to learn more about these valuable contributors in those other texts, but are left wanting in the meantime.

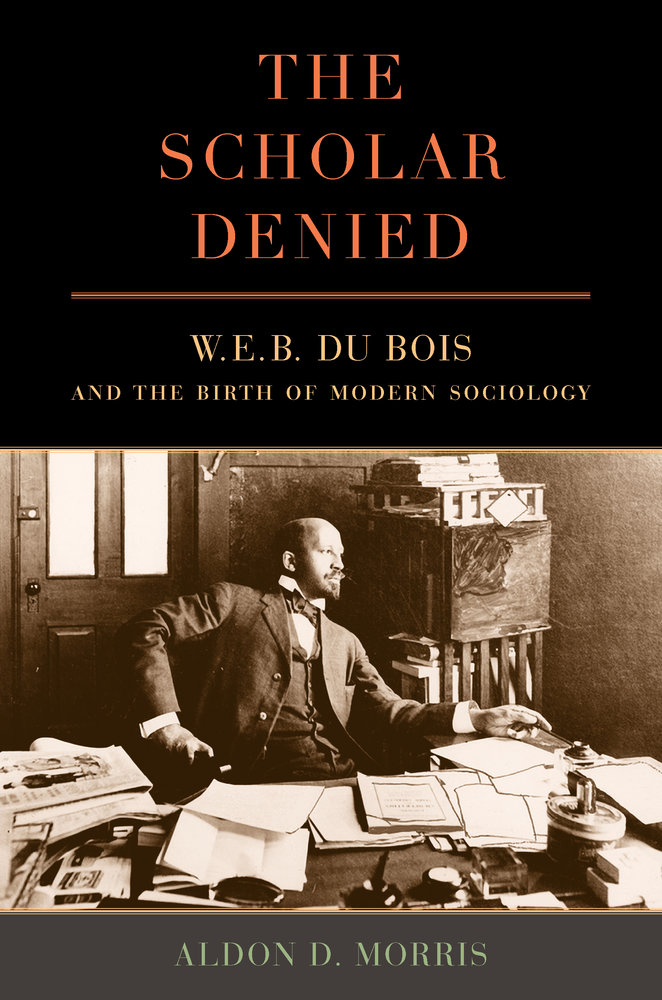

Wright’s material is not the only work on this subject. Published a year before Wright’s book and double the size, Aldon Morris’ The Scholar Denied: W. E. B. DuBois and the Birth of Modern Sociology (2015) bears noting here. As the first major book to resituate the Atlanta school as the progenitor of the discipline, Scholar Denied is impressively comprehensive in its deployment of eclectic source material to account for Du Bois’ transnational influence on early sociology. Morris’ nuanced analysis of the factors responsible for the Atlanta school’s development and marginalization is captivating. Most significantly, his meticulous research renders a compelling revisionist construction of the co-optive subterrains through which the ideas and methods of the Atlanta school penetrated mainstream sociology throughout the twentieth century, albeit without acknowledgment.

Perhaps it is unfair to compare the two authors. Wright has staked out a narrower task for his slimmer volume. But each book offers something important that is mutually reinforcing in ways that should be highlighted. For example, toward the end of his book, Wright discusses mainstream sociology’s racial milieu and the trenchant effects of systemic racism on the Atlanta school’s sidelining. In redress, he calls upon allies and advocates to insert the Atlanta school into the sociological canon. Urging action as a matter of disciplinary integrity, his petition is deft and specific. Meanwhile, in his summative chapters, Morris proffers a theoretical framework to better understand the “variegated alliances” that make possible the formation of liberatory schools of thought among “subaltern scholars” facing the constraints of a racist society.3 These are exciting ideas and prompting final notes.

There can be no doubt that the timing, extensive promotion, and wide acclaim of Morris’ book will lessen the ultimate impact of Wright’s volume on the field. But the tandem book releases also represent something greater than either book alone: timely academic protest apropos of the current insurgent political moment where the black lives matter movement and other resistors are raising urgent questions about the tactics, terrains, and arbitrariness of institutionalized power. Beyond their evidentiary merits, both books thus offer something intangible and politically necessary that speaks to the interior yearnings of many scholars of color – the yearning for recognition of our intellectual contributions, past and present, as constitutional to the genealogies of disciplinary knowledge.

In the end, The First American School is a valiant primer for sociologists, historians, and lay students of Du Bois that indexes with cogency and accessibility the contents of the Atlanta Laboratory studies and how they were accomplished. In this function, Wright makes a standalone contribution. However, if I had my druthers, I would have liked to see the inclusion of the material contained in Wright’s numerous earlier articles on the subject, updated and expanded with new evidence and argumentation. This would have made Wright’s book a more complete foundational text for the many emerging scholars of Du Bois and the Atlanta school that are certainly soon to follow Wright’s inspiring lead.

Citation: Amen, Kali-Ahset. “Book Review: The First American School of Sociology.” Atlanta Studies. May 30, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20170530.

Notes

- Martin Bulmer, The Chicago School of Sociology: Institutionalization, Diversity, and the Rise of Sociological Research (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984).[↩]

- Earl Wright II, “Why Black People Tend To Shout!: An Earnest Attempt to Explain the Sociological Negation of the Atlanta Sociological Laboratory Despite Its Possible Unpleasantness,” Sociological Spectrum 22, no. 3 (2002): 325–61; Earl Wright II, “The Atlanta Sociological Laboratory, 1896–1924: A Historical Account of the First American School of Sociology,” Western Journal of Black Studies 26, no. 3 (2002): 165–74; Earl Wright II, “Using The Master’s Tools: Atlanta University and American Sociology, 1896–1924.” Sociological Spectrum 22, no. 1 (2002): 15–39; Earl Wright II, “W. E. B. Du Bois and the Atlanta Sociological Laboratory,” Sociation Today 3, no. 1 (2005); Earl Wright II, “W. E. B. Du Bois and the Atlanta University Studies on the Negro, Revisited,” Journal of African American Studies 9, no. 4 (2006): 3–17; Earl Wright II and Thomas C. Calhoun, “Jim Crow Sociology: Toward an Understanding of the Origin and Principles of Black Sociology Via the Atlanta Sociological Laboratory,” Sociological Focus 39, no. 1 (2006): 1–18; Earl Wright II, “Deferred Legacy!: The Continued Marginalization of the Atlanta Sociological Laboratory,” Sociology Compass 2, no. 1 (2008): 195–207; Earl Wright II, “Beyond W. E. B. Du Bois: A Note on Some of the Lesser Known Members of the Atlanta Sociological Laboratory,” Sociological Spectrum 29, no. 6 (2009): 700–17. Earl Wright II, “Why, Where and How to Infuse the Atlanta Sociological Laboratory into the Sociology Curriculum,” Teaching Sociology 40 (2012): 257–70.[↩]

- Aldon Morris, The Scholar Denied: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Birth of Modern Sociology. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015), 193.[↩]