“Certainly,” Jim Auchmutey of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution writes, Atlanta is “the gay oasis of the South—the place with the most gay bars and the most gay churches” of any city in the southeastern United States. 1

Published in a 1987 series titled “The Shaping of Atlanta,” Auchmutey’s article describes the “influences” and numerous contributions of gay and lesbian Atlantans from their power as a voting bloc to their “renovation of intown neighborhoods.” As numerous and powerful as they may be, Auchmutey notes that “no one interviewed for [his] article could name a single prominent Atlantan who is openly gay.”2 Further, Auchmutey’s article depicts a tension among Atlanta’s gay-and-lesbian-identifying citizens between those who desire more out, overt, and direct political action and those who do not see a need for such activist organization. Auchmutey interviews Atlanta business-owner Frank Powell, who states, “Reputable gay people don’t carry signs in the streets. I see those people on the news and they look like creatures out of a weird movie. I would never do that. I have nephews and nieces in this town, and I don’t want to embarrass them. They must know about me; I’ve opened 13 bars here and every one has been gay as a goose. But I don’t have to flaunt it.”3

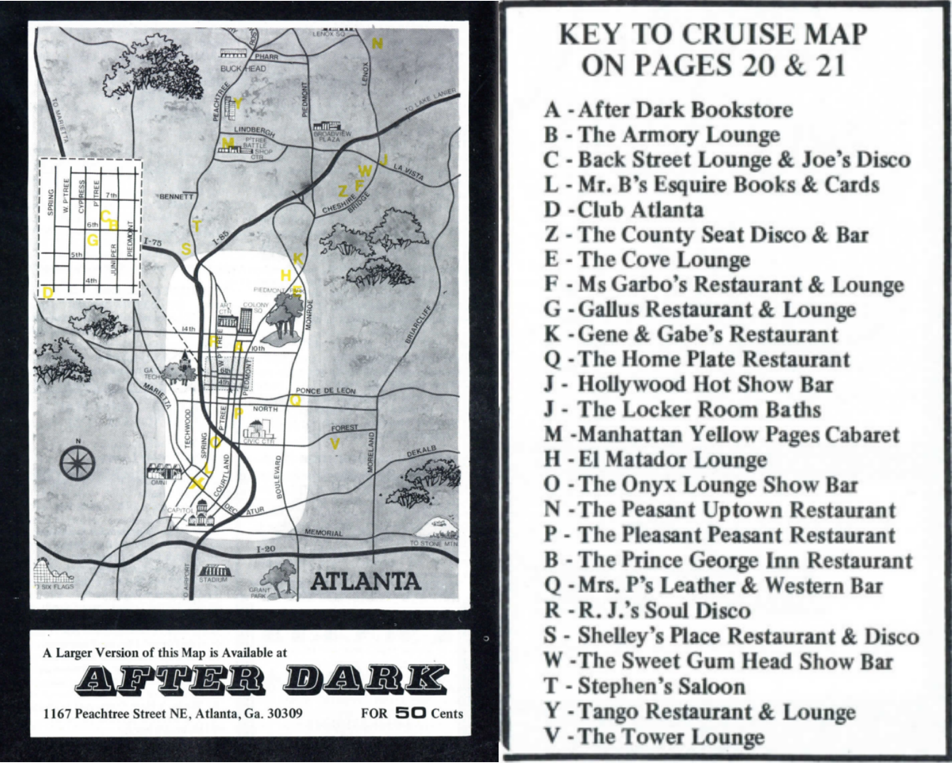

Powell repeated similar beliefs in various instances across his long career as the “prominent,” “gay as a goose” Atlanta business-owner of such bars as the Cove, the Conference Room, Ms. Garbo’s, Peyton Place, County Seat, Frank Powell’s, and the Sweet Gum Head, which was known from its opening on November 13, 1971, until its closure on August 30, 1981, as the “Showplace of the South” at 2284 Cheshire Bridge Road. Powell’s lack of political action and personal beliefs on the tactics of gay and lesbian activists makes it all-the-more ironic that one of the first book-length histories of “Atlanta’s gay revolution” centers around this second bar he owned, The Sweet Gum Head. The Gum Head was named after the little town where Powell grew up, from where he moved to Atlanta in 1959, and in which he would be buried following his death in 1996: Sweet Gum Head, Florida.

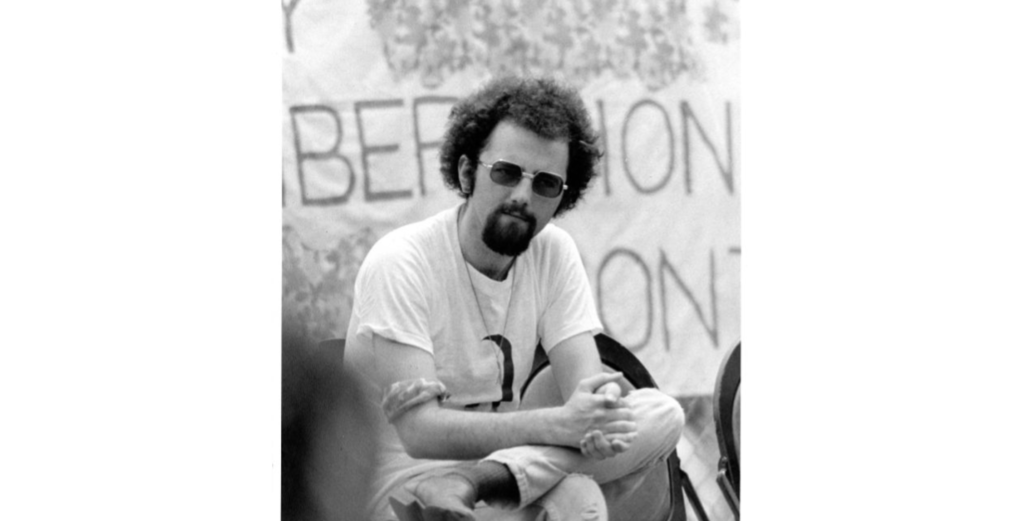

Like Auchmutey’s brief survey of gay Atlanta in the late 1980s, Martin Padgett’s 2021 history, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head: Drag, Drugs, Disco, and Atlanta’s Gay Revolution, invites readers to trace the development, prominence, and influence of Atlanta’s gay community through Padgett’s carefully curated cast of important cultural, business, and political figures across the 1970s. Unlike Auchmutey’s article, Padgett’s study both identifies and continues interviews with numerous “prominent” gay Atlantans that shaped Atlanta’s gay community, some who carried signs in the streets and some who flaunted it in the bars. Though A Night at the Sweet Gum Head (ANATSGH) features a larger cast, Padgett places “two men” who came to Atlanta “once upon a time” at the center stage of his narrative: the late activist-publisher Bill Smith and former drag performer John Greenwell/ Rachel Wells.4

Each of Padgett’s chapters spotlights a specific person within the Sweet Gum Head orbit. In his organizational choice to follow Smith, Greenwell/Wells, and other “cast” members, Padgett is perhaps inspired by the work of Martin Duberman, whose 1993 Stonewall similarly traced a handful of historic actors involved in the 1960s-1970s “gay revolution” that encircled the events at the Stonewall Inn and bar in New York City’s Greenwich Village. With ANATSGH Padgett intentionally casts Atlanta as a central site of local queer worldmaking, placing the city in the company of the more often celebrated hubs of 1970s gay liberation like New York City and San Francisco. “Atlanta was not New York or San Francisco,” Padgett writes, “but it was critical to the gay civil-rights movement. If the movement were to succeed in the South, it would have to succeed in Atlanta.”5

Whereas Auchmutey viewed Atlanta as a continued “oasis” in 1987 in its continual attracting of men and women like Frank Powell from small rural towns across the southeast, Padgett understands Atlanta in the 1970s as “a relatively progressive oasis surrounded by ultraconservative mores.”6 Padgett views the “shaping of Atlanta” as inseparable from the “gays and lesbians” who “streamed in from places” across the south and “fashioned an oasis” in the city, largely beginning in his view during the 1970s.7 For lesbian and gay southerners, Padgett writes, Atlanta served as a “mecca, a nirvana, an Oz.”8 This truth is also a trope, to paraphrase a comment Padgett made in conversation with Samantha Allen, and such a trope of Atlanta as “oasis,” as “mecca, nirvana, Oz” did not easily map onto to the lived experience of queer people within the city. For example, Padgett’s story of Bill Smith, an early pioneering gay activist who died of an overdose in 1980, highlights both the promise and collapse of possibility for gay people in the city.9 “I looked at [the book] as an anti-fairy tale,” Padgett states, and references to The Wizard of Oz lore permeate ANATSGH.10 Though Atlanta “drew gays and lesbians from all over the South,” in Padgett’s account such an oasis was by definition fleeting, an Emerald City mirage ultimately undone by internecine bar wars, drug culture, broader culture wars, and the advent of the HIV/AIDS crisis.11 Padgett’s final chapter, “Midnight at the Oasis” (once a working title for the book), describes the closure of the titular performance “oasis,” the Sweet Gum Head on August 30, 1981, nearly two months to the day following the publication of a New York Times story describing a “Rare Cancer Seen in Homosexuals.”12

“AIDS hit the city at a strange time,” Bill Gripp, a Midtown psychologist and member of the Atlanta Gay Center board, tells Auchmutey in 1987. “The gay community here seemed to be on the verge of breaking out of the bar culture and becoming more politically active.”13 Though Padgett includes elements of tragedy, he focuses his study before this “strange time,” more closely following the pleasures found in Atlanta’s gay “bar culture” of the 1970s. When AIDS began, “This whole decade of happiness and discovery and optimism got put aside,” Padgett states, “I want[ed] to do . . . something about a happier time.”14

*

Certainly, happy times at the Sweet Gum Head are central to Padgett’s staging of Atlanta’s gay revolution as it challenged the conservative mores of greater 1970s Atlanta. In Gay Bar: Why We Went Out, published the same year as Padgett’s ANATSGH, Jeremy Atherton Lin writes, “A gay bar can be a repository for all the extra that doesn’t fit into other spaces,” and Padgett’s narrative weaves together an ample amount of queer extra, from disco and drug laden nights of debauchery to drag infused scenes of joy, triumph, and community building.15 In Padgett’s study, such countercultural scenes exceeded Atlanta’s community of conservative concerned citizens’ capacity to understand and therefore served as incubators of a distinctly gay political revolution in the city. Many of Padgett’s scenes of “extra” begin and reverberate from the titular Sweet Gum Head.

Lin’s Gay Bar highlights his firsthand experiences of a series of gay bars in cities like San Francisco, London, and Los Angeles in contrast to Padgett’s focus on historic actors. However, the two books mirror one another in articulating what Lin understands “gay” to be: “an identity of longing” that contains “a wistfulness” in “beholding it in the form of a building, like how the sight of a theater stirs the imagination.”16 Both Lin and Padgett behold gayness “in the form of [past] building[s].” Whether Lin’s The Factory or Padgett’s Sweet Gum Head, the gay bar as a structure “affords refuge” as a figurative “approximation of neverland” that “evinces a mind-set of perennial searching.”17 Lin’s reference to “neverland” and Padgett’s frequent reference to the Sweet Gum Head as “Oz” and an “oasis” speak to the ongoing sense of gay bars as sites of a fantasy promised if not always delivered — what Padgett described as the “anti-fairy tale.” “Gay bars are about potentiality, not resolution,” Lin writes, noting that “going to the gay bar has always been about the expectation.”18 Such longing, perennial searching, potentiality, and expectation encircle fantasy in both erotic and political dimensions: the gay bar, then, in both Lin and Padgett’s past-oriented works remains a site through which to search for queer pasts, to imagine queer futures, and to build networks of queer resistance in the present that exceed the structure’s central functions as entertaining refuge, performative site of identity negotiation, and cruising ground for intimate encounter.

Though not as explicitly a defense of the importance of gay bars or a critique of the rapid disappearance of gay bars today as Lin’s book, Padgett engages this line of thought, staging his historical examination of the development of 1970s gay Atlanta from perhaps the city’s most famous gay “show place,” a site that has been closed for forty-one years. In returning to the Sweet Gum Head, Padgett asks reflective questions of his readership: what would it mean if sites like the Sweet Gum Head remained in Atlanta today along a rapidly changing Cheshire Bridge strip? What would it mean for the Sweet Gum Head’s highly theatricalized fantasy to have broken the gay bar’s fourth wall and become a more-lasting permanent reality for gay and lesbian people in Atlanta?

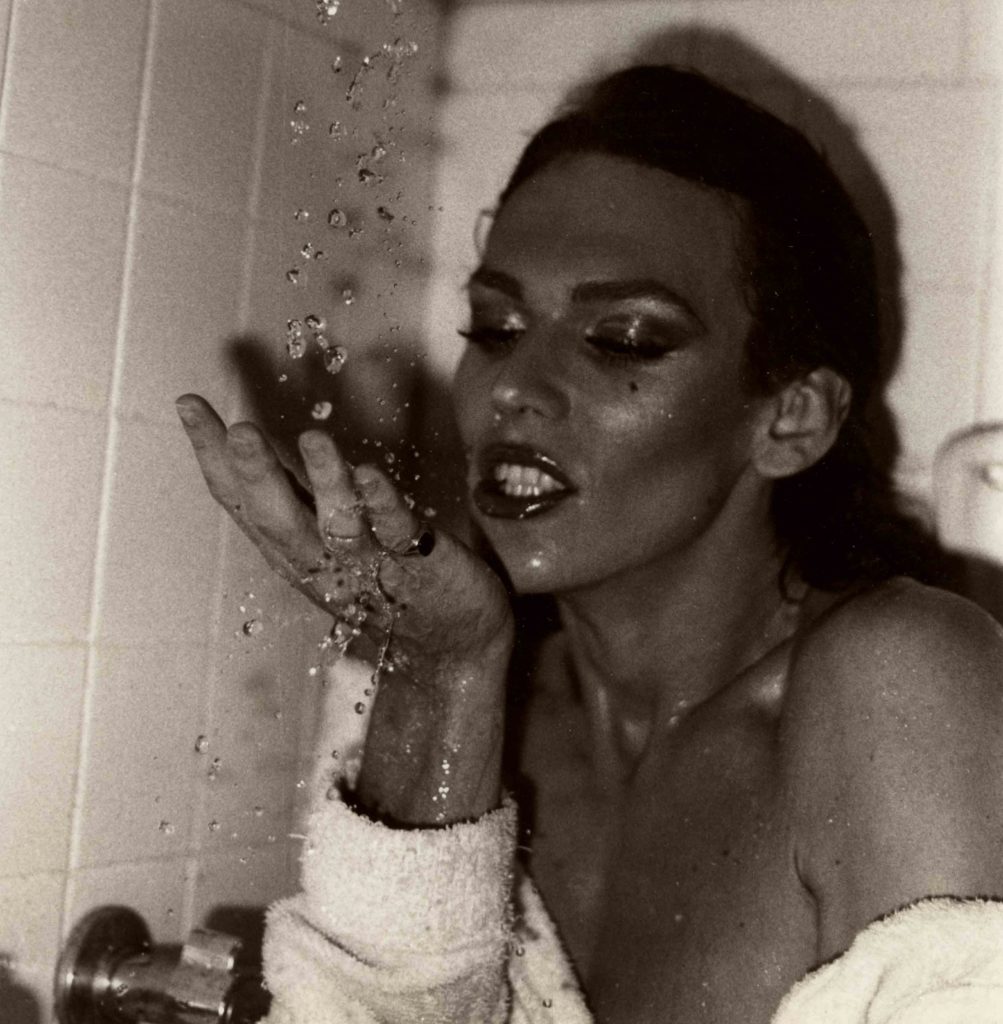

Though such questions are implicit and unanswerable in ANATSGH, Padgett’s theatrical organization and frequent motifs “stir the imagination” and invite readers to look to the past in tracing how queer Atlantans fashioned themselves on the Sweet Gum Head stage and beyond during the short decade of its existence. Padgett cites a contemporary reviewer of one Sweet Gum Head performer, “Theatre is the basic metaphor of our lives. Gays must invent—write—themselves, drastically in order to hold jobs, rent apartments, be noticed in bars, etc. . . . Gay life is so theatricalized that we can do nothing but act out scenes, day and night.”19 Though populated by a cast of prominent gay Atlantans and featuring Bill Smith and John Greenwell/ Rachel Wells as top-billed performers, the Sweet Gum Head is the central character in Padgett’s study through which both the author and his subjects invent, “act out,” and “write” their “scenes” of gay Atlanta. Aside from the professed beliefs of gay business owners like Frank Powell, Padgett understands that nightlife establishments like the Sweet Gum Head played an important role across the 1970s as sites of connection and resistance that popularized drag and disco in Atlanta, launched the careers of performers like Rachel Wells (photographed below), and complemented the more direct political efforts of gay activists like Bill Smith, Klaus Smith, Berl Boykin, and Charlie St. John.

Sites in the built environment like the Sweet Gum Head served as safe havens and protected containers in which gay men and women could “flaunt it,” to rewrite Powell, without the fear of ostracization, persecution, or prosecution even as they “welcomed the kind of rebels that Frank Powell hated.”20 As the late Ray Kluka, director of the Atlanta Gay Center and editor with Etcetera magazine, told Jim Auchmutey in 1987, gay bars “occupied the same sort of place in the gay rights movement as churches did in the black civil rights movement.” In inviting readers to A Night at the Sweet Gum Head, Padgett encourages us to understand the sacred centrality of gay bars to the development of Atlanta’s LGBTQ+ community and politics as well as the origin of Atlanta’s reputation as drag capital of the South and a southern oasis for queer folk across the latter half of the twentieth century. According to Bill Smith, a central subject of Padgett’s study, in 1974, Atlanta had seventeen gay bars, up from just three in 1969, the date with which Padgett’s study begins.21 While Padgett’s book traces the proliferation of some of these gay and lesbian spaces in 1970s Atlanta (sites include Chuck’s Rathskeller, Mrs. P’s, Club Centaur, Cabaret After Dark, Mother’s, the Locker Room, Union Station, the Yum Yum Tree, Hollywood Hot, Timbers, Numbers, and Illusions), the Sweet Gum Head takes center stage. Throughout Padgett’s book, he describes the title venue in fantastic, ephemeral, and hedonistic terms: an “oasis of profanity” (47), “safer space” (106), “Oz” (151), “a clubhouse fueled by an undercurrent of hedonism,” “the drag tabernacle of the South” (215), “one of Atlanta’s more notorious nightclubs” (217), and “the oasis where they all had paused on the journey to places unknown” (172).

Though once legion, Atlanta today has few exclusively gay and lesbian bars or clubs. Is the gay bar a stop on a queer person’s journey to places unknown? And what do we make of the disappearance of such formative if temporary sites of potentiality? In Gay Bar, Lin writes, “Perhaps the bars were only ever meant to be a transitional phase,” echoing José Esteban Muñoz’s subversive expansion of “stages” as both a temporal “phase” and a spatial utopic structure through which to imagine and enact the potential that is queerness.22 In our current phase witnessing the disappearance of the once ubiquitous gay bar, from where might actors stage and imagine queer futures? Though the times have changed, such a question is not new in thinking about the horizon of gayness and potential queer futures; in an October 1978 guest editorial for Blueboy Magazine, the “national magazine about men,” James Tyson writes, “There will always be gay bars and gay discos and exclusively gay activities. But, with any luck, we’ll be able to shed our ghetto mentality and feel sufficiently self-confident and at home in society to relax and be people, as opposed to homosexuals.”23

Though some among us have become with “luck” more seen as “people” in the eyes of the law and majority culture in the last five decades, queer spaces—both the important, literal stages of bars and sites of drag as well as the digital stages and websites framed by the proscenium of a smartphone’s borders—continue to perform as places to search for queer pasts, to build networks of queer resistance in the present, and to imagine queer and trans futures for all. “Who we are is never permanent,” Padgett writes, and attention to a succession of impermanent gay bars remains one way through which we imagine our changing identities as LGBTQ+ Atlantans.24 “Identity,” Lin similarly writes, “is articulated through the places we occupy, but both are constantly changing.”25 Though the Sweet Gum Head closed in 1981, though numerous gay bars have come and gone in Atlanta since then, though changes in identity and spatial development are inevitable, Padgett’s book reminds us that “the best performances,” to quote Muñoz, “do not disappear but instead linger in our memory, haunt our present, and illuminate our future.”26 Padgett’s study captures some of those indelible shapeshifting performances.

*

Certainly, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head fulfills the author’s commitment to spotlighting the importance of performative places like the Sweet Gum Head in shaping Atlanta’s gay community, lingering in our memory, haunting our present, and illuminating the future. However, the text is far from complete. In centering the Sweet Gum Head, Padgett invites inquiry into other stages and sites. As such, it is important to note that Padgett’s book does not aim to be and cannot be fully inclusive or representative of Atlanta’s gay and lesbian community in the 1970s. As the title evinces, it is “a night” among many nights, spotlighting one space among a constellation of gay and lesbian spaces in the city. “By 1977,” Padgett writes, “the story of Atlanta read more like an encyclopedia of cultures instead of a single culture’s monograph,” and ANATSGH does not make a definitive argument for or against the success of Atlanta’s gay and lesbian movement as a multiracial, multidimensional, intersectional coalition.27 Rather, Padgett follows other historians of gay Atlanta in understanding that his single history organized tightly around one locale cannot tell the full story. As Wesley Chenault and Stacy Braukman write, “The history of a place, a group of people, or political and social change can never be neat and tidy.”28 Though Padgett’s structure is neatly delineated and theatrically framed, his narrative is neither neat nor tidy. Padgett echoes Chenault and Braukman in understanding that “there is no single profile that fits gay and lesbian Atlantans,” but “the histories of these men and women are inseparable from the history of the city itself.”29

Though Padgett resists offering ANATSGH as a single representative profile, questions arise as to why certain people and organizations that would seem “inseparable” and important to 1970s gay and lesbian Atlanta were not included in Padgett’s study. Certainly, Bill Smith and the Community Relations Commission, the founding and disillusion of the Atlanta Gay Liberation Front, early gay pride marches, protests over the Atlanta Constitution’s firing of out-gay-man Charlie St. John, the multi-year run of Bill Smith’s The Barb, vacillating support from Vice Mayor and then Mayor Maynard Jackson, protests of Anita Bryant’s presence in 1978 Atlanta, among others, are important figures and events, and Padgett amply features them. But what of the concurrent force that was the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA), the ALFA houses, and ALFA’s influential newsletter?30 How would the narrative expand and shift by spotlighting lesbian bars, like the Frank Powell owned Ms. Garbo’s or the iconic Tower Lounge, in addition to the Sweet Gum Head? What of historic actors like Lorraine Fontana or events like the 1975 Great Southeast Lesbian Conference? What of Radio Free Georgia programming or the opening of Charis Books and Christopher’s Kind bookstore?

The gay of Padgett’s subtitle must be taken quite literally, then, to mean gay white men: A Night at the Sweet Gum Head neither spotlights the widely available record of the lesbian feminist movement in Atlanta during the 1970s nor does it delve in a sustained manner into the role race played in the development of this southeastern “gay revolution.” Though framed around the experience of two white gay-identifying men, Padgett’s book noticeably lacks the inclusion of concurrent developments in Atlanta’s black gay community. As E. Patrick Johnson reminds, “black gay southerners have co-existed in communities throughout the region for as long as there has been a ‘South.’”31 Perhaps, Padgett’s work could have mentioned the legendary Marquette lounge at 868 Joseph E. Boone Blvd NW or the development of the Gay Atlanta Minority Association or GAMA. Greg Worthy co-founded GAMA in 1979 — near the temporal end of Padgett’s study — to address issues of racism within the gay community and amplify black gay and lesbian voices in the city’s political arena. In States of Desire: Travels in Gay America, Edmund White reflected on the white gay and black gay communities in visiting Atlanta in the 1970s, “the two worlds are utterly separate. This is not a matter of cultural isolation but of deliberate exclusion. The gay bars are owned and operated by whites and the policy is to keep blacks out.”32 GAMA’s explicit goal was to “openly attack the separatism practiced by many local gay bars and adult entertainment centers.”33 Though Padgett’s book captures the role the black community played — from cautious political support offered by the city’s first black mayor Maynard Jackson to the influence of the Civil Rights Movement blueprint — in the rise of Atlanta’s politically active gay and lesbian movement, the book lacks insight into how black gay men and lesbians may have felt about the central “entertainment center” or “showplace” of Padgett’s book, the Sweet Gum Head. Did the Gum Head, like After Dark and other Atlanta establishments, “keep blacks out” to use White’s expression? How did both Bill Smith’s work with the Georgia Gay Liberation Front and Greg Worthy’s work with GAMA anticipate the work of organizations like Black and White Men Together in the 1980s?

Such questions are not meant to serve as mere critique but rather as critical openings that Padgett’s work offers for further research.34 Padgett understands the importance of multiple narrators in telling the story of Atlanta. He writes in his “Preface,” “this is our story,” and in my personal copy of ANATSGH, Padgett signed “Eric — This is our history” following his talk with the AJC’s Jeremy Redmon at the 2021 Decatur Book Festival.35 On one level, Padgett’s inscription is correct in its direct address to me; as two white gay men of different generations — Martin and Eric — who both moved from rural southern spaces to Atlanta, ANATSGH is our history, closely aligned with figures we might think of as direct “gay elders.” However, Padgett would recognize that his book does not depict everyone’s history within our community. As beautifully written and intricately staged as it is, ANATSGH is not a fully dimensional portrait of Atlanta’s queer community in the 1970s. Padgett has made choices based upon the archival evidence and interlocuters available to him. His work echoes one of his central subjects, Rachel Wells, who in competing for Miss Gay America in 1979, stated “I will not try to represent the gay community as a spokesperson for such a diverse group.”36 ANATSGH does not try to represent the full diversity of 1970s gay and lesbian Atlanta, and on some level, that allows Padgett to delve more deeply and intimately into his subjects and scenes. Far from representative, ANATSGH contributes one version of “our” story, and invites more of us to tell fuller, more diverse, and more inclusive versions of Atlanta’s LGBTQ+ past.

One of Padgett’s chief successes, then, is his careful and detailed attention to his selected cast of characters. He organizes each of his scenes around an important figure, and he proves a skillful choreographer, adroitly connecting disparate strands between disparate figures. Sometimes such scenes coalesce into linear narrative but more often they evoke snapshots within a panorama of experience. Bill Smith and John Greenwell/Rachel Wells receive the most complete of the linear-chronological narratives in the study, but even their experiences cannot be fully known or depicted in Padgett’s work. The two central thorough-lines of ANATSGH follow Padgett as he traces Bill Smith’s rise and fall and John Greenwell’s on-again, off-again relationship with his stage persona Rachel Wells. More often than not, Padgett refrains from speculating what cannot be either verified in the historical record or corroborated via his eyewitness interlocuters in regard to Smith and Greenwell/Wells. Padgett often relies on modal verbs to convey possibility; see, for example, his frequent repetition of the verb “may” in describing the series of events that led to Bill Smith’s ultimate death.37 One exception to this occurs when Padgett seems to veer from scholarly sourcing to speculation when he attempts to imagine and more fully depict Smith’s deteriorating mental state: “Imprisoned in his own room, under a doctor’s order, he imagined how Robbie’s confinement felt, how much it felt like his own. Cruel.”38 Though a minor criticism in an otherwise careful book, because such an instance is not directly tied to a source (either Bill Smith’s writing or archives or Padgett’s direct conversations with Smith’s friend Gary Poe), one is left to question the strength of such a claim. Did Bill Smith really understand his situation as “cruel”? Did he really view his situation as similar to the incarceration of a gay Atlanta man convicted of murder, Robbie Llewellyn? Is it possible to know his mental state? Is it fair to make that claim? Here, Padgett may have pulled from concepts such as Saidiya Hartman’s “critical fabulation” to support his claims.

Another example of Padgett’s inability to capture a “fuller” portrait concerns Bill Smith’s co-lead in the study, John Greenwell/Rachel Wells. If we understand the gay bar to be a space of potentiality in which queer subjects negotiate their identities and cruise for erotic encounter, a frustration of mine throughout the text was a lack of attention to the affective and sexual lives of some of the central subjects. One cannot, after all, discuss the “gay revolution” without attention to the attendant sexual liberation and a revolution of social affect and interpersonal intimacy central to movement thinking in the 1970s. Though Bill Smith’s love life receives some attention, Padgett refrains from mentioning any direct sex-love-life experiences of Greenwell/Wells. Off stage and out of drag, we receive glimpses into Greenwell’s family and home life but not much else. As such, the portrait we receive of Greenwell never feels “fully” dimensional even as Padgett relies on his firsthand conversations with Greenwell to avoid speculation. Though I may have been frustrated during the reading of ANATSGH — wanting more of Greenwell “off stage”— Padgett’s authorial decision seems ultimately a commendable one shaped by a researcher’s respect of his subject. Padgett writes in his “Aftershow” coda: “When we met for the first time, in 2016, John told me there would be parts of his story that would remain his to tell.”39 Greenwell has published a memoir, and one hopes Greenwell will tell more of his own stories to add to the careful narrative Padgett has crafted of him.

Beyond Smith and Greenwell/Wells, other characters on Padgett’s stage — Maynard Jackson, Larry Edwards/ Hot Chocolate, Cliff Montalbo/ Dina Jacobs, Alan Orton/ Lavita Allen, Clay Hester/ Satyn DeVille, John Austin, Charlie Dillard/ Charlie Brown, Heather Fontaine, Phillip Forrester/ Diamond Lil — may be important to the overall narrative arc Padgett crafts, but they receive considerably less attention and detail. Although arguably limited by extant archives and sources, one wonders the effect their more substantive inclusion on the ANATSGH stage would have on the “revolution” Padgett surveys. Nevertheless, Padgett invites readers to conduct the critical bridgework his scenes require, and like a gay bar, ANATSGH is a fantastic repository for all the extra that could not possible fit within the confines of Padgett’s 324 pages.

“Enough time has passed,” Lin writes, “that gay bars, once a scourge, have become monumental in their own way. But their vastly undocumented history requires transcribing.”40 Put another way, “Queer life,” anthropologist Gayle Rubin writes, “is full of examples of fabulous explosions that left little or no detectable trace,” and Padgett’s narrative goes beyond mere documentation and transcription of one era of “fabulous explosions” in Atlanta queer life and invites readers to trace, transcribe, and locate other such fabulous moments.41 With the cinematic quality of each of Padgett’s successive scenes, readers function as film editors, capable of suturing together even the most oblique of traces to begin to create their own narrative of “Atlanta’s [LGBTQ+] Revolution” in the 1970s and beyond. As such, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head serves as a remarkable launchpad for future researchers of gay bars and queer lives that have populated Atlanta’s LGBTQ+ history.

*

Certainly, the queer journeys central to ANATSGH continue to matter. These days, when I drive into Atlanta after some time away, I most often travel I-20 East from my native Mississippi. As I crest the hill at the Lithia Springs exit near Six Flags, the midtown-downtown Atlanta skyline is visible as if an Emerald City. “Once upon a time,” Padgett writes, “two men,” Bill Smith and John Greenwell, “had run away from home” to a “city that shrouded itself in an emerald forest.”42 Viewed from this hilltop distance, Atlanta’s “emerald forest” continues to resemble a southern Oz that calls to “friends of Dorothy” and those who continue to refuse, like Smith and Greenwell, to stay home in oppressive environments where they face isolation and subjection to legal curtailments of their lives and freedoms. Certainly, many still refuse to stay home and “be the town queer.”43 Despite differences in temporal context, “certainly” Atlanta remains a site of sanctuary and belonging for queer southern lives.

Atlanta, viewed from this direction, is less an Emerald horizon imbued with potentiality and more a succession of drab green road signs pointing wayward travelers toward home.

Though Padgett views ANATSGH as an “anti-fairy tale” where there are neither simple nor happy endings for those who journey to Atlanta-as-Oz-as-oasis, Padgett recognizes the importance of documenting this history — the ideal and the real — for those still in search of their own complicated sites of belonging. On a daily basis, I approach Atlanta from I-20 West, leaving Emory’s Oxford College where activist and publisher Bill Smith was once an undergraduate student for a year and near where his memorial service was held in Covington in 1980 following what Padgett writes as his deliberate overdose. Atlanta, viewed from this direction, is less an Emerald horizon imbued with potentiality and more a succession of drab green road signs pointing wayward travelers toward home. Padgett’s work approaches Atlanta’s queer history with the utopic-potential, the realistic-mundane, and the tragic dimensions in mind, and in so doing, provides a complex if incomplete portrait of 1970s Atlanta. It is up to the rest of us queer travelers to build upon the path making work Padgett has published.

Though Padgett’s study is but one version of the development of Atlanta’s gay and lesbian community, it performs the queer ethic of one of its central subjects, Bill Smith, who, as Padgett writes, “wanted to create a road map for an existence that had no map, no route, no safe stops along the way.”44 In his 1975 “Editor’s Notebook” for The Barb, Bill Smith reflected on meeting pioneering gay activist Frank Kameny when he visited Athens, Georgia to deliver a talk to university students. Smith writes what he learned from Kameny, “If you want the equal protection of the law, if you want a law that protects your ability to maintain a job, housing and public accommodations you must ask for it, work for it. No one gives a share of a table to anyone, it must be taken with the dignity and pride of personhood.”45 A Night at the Sweet Gum Head stages the dignity and pride of a few “prominent” gay Atlantans coming into their full “personhood,” and it invites us to remember those who forged the roads we now travel as we continue to create road maps of our own for those who come after. Bill Smith may not have lived to see the oasis at the end of the road he envisioned, but his work created a blueprint for others to follow. Padgett’s book reminds us that the central thrust of queer studies is to document both the “happier times” and the tragedies of queer people and places so that we may give realistic hope to queer and trans folk who have not yet found exit ramps to an “oasis” like the Sweet Gum Head full of an evolving roster of chosen family. Harvey Milk famously stated, “without hope the us’s give up.”46 In these times of book banning, heightened surveillance of curricula featuring LGBTQ+ history, and ongoing reminders of “ultraconservative mores” and resistance to our lives, the work of staging queer as a series of scenes depicting a welcoming oasis of potentiality must persist. Like “creatures out of a movie” marching in the streets or performing beneath the glittering lights of the stage, our work continues, certainly.

“It is my belief that minoritarian subjects are cast as hopeless in a world without utopia.”

—José Esteban Muñoz47

Citation: Solomon, Eric. “Once Upon a Time in Atlanta: Staging Revolution from the Gay Bar.” Atlanta Studies. August 10, 2022. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20220810.

Author Bio: Eric Solomon is a visiting assistant professor of English and American Studies at Oxford College and editor of the “Queer Intersections” series with the journal Southern Spaces. He is project manager of the #TUOR Project, a digital story tour of queer sites in Atlanta’s built environment. He serves as member of the board of directors and secretary of Historic Atlanta (HA), which works to advance social justice and community by saving historic places. He also chairs HA’s LGBTQ+ historic preservation advisory committee. Hard at work on a book project, Solomon’s publications have appeared or are forthcoming in a variety of journals, including Mississippi Quarterly, south, Southern Spaces, and South Atlantic Review.

Notes

- Jim Auchmutey, “The Shaping of Atlanta: Part 5: Three Communities,” Atlanta Journal and Atlanta Constitution, August 13, 1987, Local News, A1. Accessed January 6, 2022.[↩]

- Auchmutey, “The Shaping of Atlanta.”[↩]

- Padgett cites part of Auchmutey’s story in one of his brief snapshots of Frank Powell in ANATSGH. See Auchmutey. [↩]

- Martin Padgett, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head: Drag, Drugs, Disco, and Atlanta’s Gay Revolution (New York: W.W. Norton, 2021), 311. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head, 76.[↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head, xii. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head, 4. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head, 28.[↩]

- A Night at the Sweet Gum Head: Drag, Drugs, Disco, and Atlanta’s Gay Revolution by Martin Padgett, Charis Books and More, Conversation with Samantha Allen, July 15, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4RJz6QHCaVs.[↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head, 14. [↩]

- Martin Padgett, “A Conversation with J.R. Greenwell,” Chelsea Station, July 14, 2018, https://www.chelseastationmagazine.com/2018/07/a-conversation-with-jr-greenwell.html. [↩]

- Auchmutey. [↩]

- See Charis Books and More, Conversation with Samantha Allen. [↩]

- Jeremy Atherton Lin, Gay Bar: Why We Went Out (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2021), 38.[↩]

- Lin, Gay Bar, 13.[↩]

- Lin, Gay Bar, 32.[↩]

- Lin, Gay Bar, 247, 266. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head, 223. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head, 33. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head, 88.[↩]

- Lin, Gay Bar, 10; José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, 10th Anniversary Edition (New York: NYU Press, 2019), 99.[↩]

- James Tyson, “Guest Editorial,” Blueboy, October 1978, 3. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Gum Head, 286. [↩]

- Lin, Gay Bar, 250. [↩]

- Muñoz, Cruising Utopia, 104. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Gum Head, 174.[↩]

- Wesley Chenault and Stacy Braukman, Images of America: Gay and Lesbian Atlanta (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008), 7.[↩]

- Chenault and Braukman, Images, 7–8. [↩]

- “ALFA grew out of the failures of an earlier alliance that attempted to unite gay men and women, the Georgia Gay and Lesbian Task Force,” see Auchmutey. [↩]

- E. Patrick Johnson, Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2008), 1. [↩]

- Edmund White, States of Desire: Travels in Gay America (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1980), 241. [↩]

- “GAMA — Gay Atlanta Minority Association,” Gaybriel, August 3, 1979. Atlanta History Center, Atlanta Lesbian and Gay History Thing, Box 33. See also, Angelica Danielle Marini, “‘Looking for a City’: Community, Politics, and Gay and Lesbian Rights in Atlanta, 1968-1993” (doctoral dissertation, Auburn University, 2018).[↩]

- See Charles Stephens, ‘Got Something to Say’: How ATL Became the Black Gay Mecca,” Cassius, https://cassiuslife.com/66017/atlanta-black-gay-mecca/. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Gum Head, xiv. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Gum Head, 243.[↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Gum Head, 238.[↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Gum Head, 195.[↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Gum Head, 324.[↩]

- Lin, Gay Bar, 25–26. [↩]

- Gayle Rubin, “Geologies of Queer Studies,” Deviations: A Gayle Rubin Reader (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2011), 355. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Gum Head, 311.[↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Gum Head, 8. [↩]

- Padgett, A Night at the Gum Head, 71. [↩]

- Bill Smith, “Editor’s Notebook.” The Barb 2, no. 4 (1975): 2.[↩]

- Quoted in Padgett, 246. [↩]

- Muñoz, Cruising Utopia, 97.[↩]