In November 1971, the National Hockey League announced that it had awarded Atlanta businessman Tom Cousins an expansion team for the 1972-1973 season.

The club, which was soon named the “Atlanta Flames,” was the city’s fourth major professional sports franchise and marked the end of a seven-year period (1965–1972) during which Atlanta had become a “major league city” with the arrival of professional baseball (the Braves in 1965), football (the Falcons in 1966), and basketball franchises (the Hawks in 1968).1 Flames’ general manager (GM) Cliff Fletcher had originally favored the name “Rebels” for the city’s new hockey team and envisioned them cloaked in grey and red, skating on to the ice to the strains of “Dixie” played by a corps of buglers in the stands.2 However, the franchise’s local ownership vetoed the Canadian GM’s vision, believing it would damage Atlanta’s reputation as the “City Too Busy To Hate,” which they saw as central to the city’s growth in the 1960s in contrast to other Southern cities which had mired themselves in the language of “Massive Resistance.” Instead, they went with their second choice, the “Flames,” which evoked the city’s Civil War past and juxtaposed nicely with the game’s ice playing surface.3

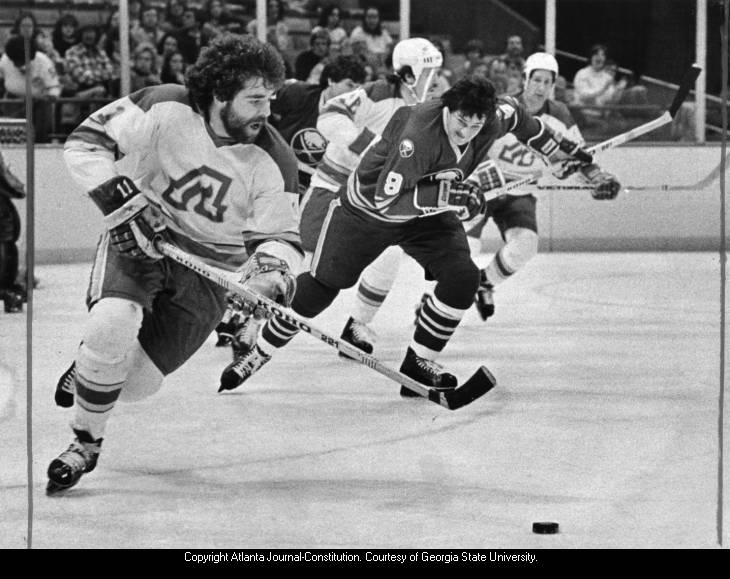

However, less than an hour before the 8 PM opening faceoff, laborers were still bolting in seats at the game’s venue, the brand-new Omni Coliseum. In fact, the game was the first event held at the Omni, the $17 million brainchild of real estate developer Tom Cousins, who, five years earlier, had envisioned the building of a multi-purpose downtown sports arena as the starting point for a full-scale revitalization of the city’s central business district. The Flames were to be one of the twin anchors of his broader remaking of downtown into a suburban-friendly site of upscale attractions and consumption along with the Atlanta Hawks, the professional basketball team Cousins had brought to the city from St. Louis a few years earlier. And the full house that watched the Flames’ October 1972 debut was no fluke. By the 1974-1975 season, the Flames had built a season-ticket holding base of more than 9,800 while averaging better than 14,000 spectators per game, both well-above the league average.4 For a moment, it seemed like Tom Cousins’ vision for the central business district had come to life.

Much like the present-day Atlanta United soccer club, the appeal of the Flames stemmed in large part from their initial success. Atlantans finally had a consistently competitive major league team to watch. While Atlanta had become a “major league city” in 1960s with the arrivals of the Falcons, Braves, and Hawks, those teams were all largely uncompetitive in the 1960s and continued to struggle in the 1970s.5 By the time of the Flames’ arrival, all of Atlanta’s other professional sports teams found themselves near the bottom of the standings in their respective leagues and among the worst-drawing clubs in their respective sports. By contrast, the Flames earned playoff appearances in six of their eight seasons in the city. Few expansion teams in any major professional sport have enjoyed as much success as the Flames did almost immediately. And the high-flying Flames of the early 1970s found an enthusiastic audience among well-to-do Northsiders and transplants from the northern United States. “It used to be the cool, charming suave sophisticated fellow about town was the one who had two tickets to a Falcons game,” the Journal’s Ron Hudspeth wrote in January 1973, “but now, it’s hockey.”6 The new evening haunt of Atlanta’s fashionable set, Flames games meant “an Omni full of suave, sophisticated Joes and little blondes.”7

Despite the Flames’ appeal as a live draw in the early 1970s, they struggled to build a broader, casual fanbase that followed the team through broadcast media. In their first year, the club had garnered excellent television ratings on WSB – which televised twenty games – drawing the third largest per capita local viewership in the NHL.8 But over the next two years, their television numbers dropped into the lower echelon of the league’s local ratings despite their presence on a powerful NBC affiliate.9 And by the second half of the decade, Flames games appeared on Ted Turner’s WTCG instead of WSB, earning the club a league-low $125,000 per season for its television rights.10 This inability to build an audience beyond their predominately affluent core of live supporters would prove to be one of the franchise’s fatal flaws.

But the Flames’ small television audience was far from the only reason that “Atlanta’s Ice Society” lasted a mere eight seasons. As the novelty of professional hockey wore off, Flames’ attendance – the team’s primary source of revenue – also declined precipitously.11 In December 1976, Georgia governor George Busbee, a fervent supporter of the club, intervened as the club’s average attendance slumped below 9,000 per game, convincing 13 large Georgia-based companies to purchase $750,000 in tickets on expense account to help steady the franchise’s finances for the remainder of the season.12 And despite the Flames’ consistent success in the regular season, the franchise’s consistent failure in the post-season (the Flames never won a playoff series) likely discouraged the more tenuous elements of the franchise’s fanbase.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Just as significant as the Flames’ declining attendance and low television ratings was the declining fortunes of their owner’s downtown real estate empire. Tom Cousins’ long-awaited $100 million mixed-use development, known as the Omni International Complex, had finally opened in 1975 adjacent to the Omni Coliseum. But its millions of square feet of office and retail space failed to become the new hub of commercial and social life in metropolitan Atlanta that he had envisioned. Instead, it became one of a number of massive, vacancy-filled, inward oriented complexes surrounding Atlanta’s central business district.13 And in March 1978, less than three years after the Omni International Complex had opened, lender Morgan Guaranty Trust announced plans to foreclose on the property.14 At the time, the foreclosure on the Omni was the largest in the history of American real estate. By May 1978, however, a consortium of national banks had orchestrated a debt restructuring plan that enabled the Omni to remain open. Nonetheless, the financial failure of the Omni International Complex brought Cousins himself to the brink of bankruptcy; between 1974 and 1977, he lost $33 million – the equivalent of approximately $172 million today, adjusted for inflation. Amidst his financial troubles, Cousins sold the franchise to Vancouver real estate mogul Nelson Skalbania, who immediately relocated the team to Calgary, Alberta for the 1980 season.15

Despite the Flames’ short tenure in Atlanta, the club’s status as the NHL’s first expansion into the South give them a unique place in the history of hockey. For a brief moment in the 1970s, the franchise had proven that a large audience for professional hockey could be found outside of its traditional bases in the northern United States and Canada. In many respects, then, “Atlanta’s Ice Society” was a forerunner to the diehard though narrow fanbases that many Sunbelt teams in the NHL have cultivated in the 21st century, including Georgia’s second though also now departed NHL franchise, the Atlanta Thrashers (1999–2011).

However, the failure of the Flames to build a long-term fanbase in the region also reflected a retreat in the metropolitan region from institutions that sought to return downtown Atlanta to its traditional status as a regional center of gravity. “I was concerned with developing 60 acres of downtown Atlanta,” Cousins said decades later of his ventures into professional sports and arena development.16 “A coliseum was the key to the whole thing, some focal point to build around.”17 The tepid response of Atlantans to their new professional sports franchises, including the Flames, would also prove to be the archetypal metropolitan Sunbelt response to the arrival of professional sports in their cities. Thus, by putting professional sports in the service of lofty civic goals, such as downtown redevelopment, elites in Atlanta and numerous other Sunbelt cities repeatedly set themselves up for disappointments as grand as the enterprises they undertook on behalf of their communities.

Citation: Trutor, Clayton. “The Rise and Fall of ‘Atlanta’s Ice Society’: Tom Cousins, Downtown Redevelopment, and Professional Hockey in 1970s Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. Dec 11, 2019. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20191211.

Clayton Trutor holds a PhD in US History from Boston College and serves as an instructor at Norwich University in Northfield, VT. He is the author of a forthcoming book on the history of professional sports in Atlanta. He’d love to hear from you on Twitter: @ClaytonTrutor.

Notes

- Al Thomy, “Atlanta Gets NHL Hockey,” Atlanta Constitution, Nov 10, 1971: 1A, 24A.[↩]

- “Omni Souvenir Dedication Book,” “Flames Magazine 1,” Sports – Atlanta Flames (Subject Folder), Kenan Research Center.[↩]

- “NHL Hockey,” Sporting News, June 3, 1972, 48; Jim Huber and Tom Saladino, The Babes of Winter: An Inside History of Atlanta Flames Hockey (Huntsville, AL: Strode Publishers, 1975), 9–10, 20–1; “Will Atlanta Embrace Hockey?” The Sporting News, October 7, 1972, 57.[↩]

- Al Smith and Warren Newman, “Skating on Thin Ice,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 30, 1980, 1D, 15D.[↩]

- Lewis Grizzard, “Loserville, USA,” Atlanta Constitution, July 11, 1975, 1A, 14A; Lewis Grizzard, “Loserville, USA: The Sahara of Pro Sports,” Atlanta Constitution, July 12, 1975, 1A, 16A; William Leggett, “Decline of a Brave New World,” Sports Illustrated, May 5, 1975, 65.[↩]

- Ron Hudspeth, “For Atlanta’s Suave Set, A New Love: Pro Hockey,” Atlanta Journal, January 12, 1973, 2D.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- “Atlanta Flames Fact Book 1975-1976,” Sports – Atlanta Flames (Subject Folder), Kenan Research Center.[↩]

- Jim Huber and Tom Saladino, The Babes of Winter, 183–4.[↩]

- Al Smith and Warren Newman, “Skating on Thin Ice,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 30, 1980, 1D, 15D.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- “Gate Slumping at Half-Million Rate,” Sporting News, December 18, 1976, 33.[↩]

- Wayne King, “Atlanta’s Upward Surge Stalls as Omni Building Complex Falters,” New York Times, February 11, 1978, 45; Jim Auchmutey, “The Omni: Neat, Clean, and Empty,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, January 6, 1985, 1B, 4B; Charles Rutheiser, Imagineering Atlanta (New York: Verso, 1996), 161–5.[↩]

- Tom Walker, “Resolution Said Close on Omni Troubles,” Atlanta Journal, March 6, 1978, Omni (Subject Folder), Kenan Research Center.[↩]

- Craig Custance, “Old Flame(s),” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, January 23, 2008, 1D; “Skalbania Buys Flames,” Sporting News, June 14, 1980, 50; Eric Duhatschek, “Skalbania’s New Flame is Calgary,” Sporting News, October 18, 1980, 30; Tom Tucker, “Kent Denies Story of Bid for Flames,” Atlanta Journal, April 17, 1980, 1D; Alan Truex, “The Ice Age: From Blizzard to Meltdown,” Atlanta Journal, May 23, 1980, D1.[↩]

- Jeffrey Denberg, Roland Lazenby, and Tom Stinson. From Sweet Lou to Nique (Atlanta: Longstreet Press, 1992), 30.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]