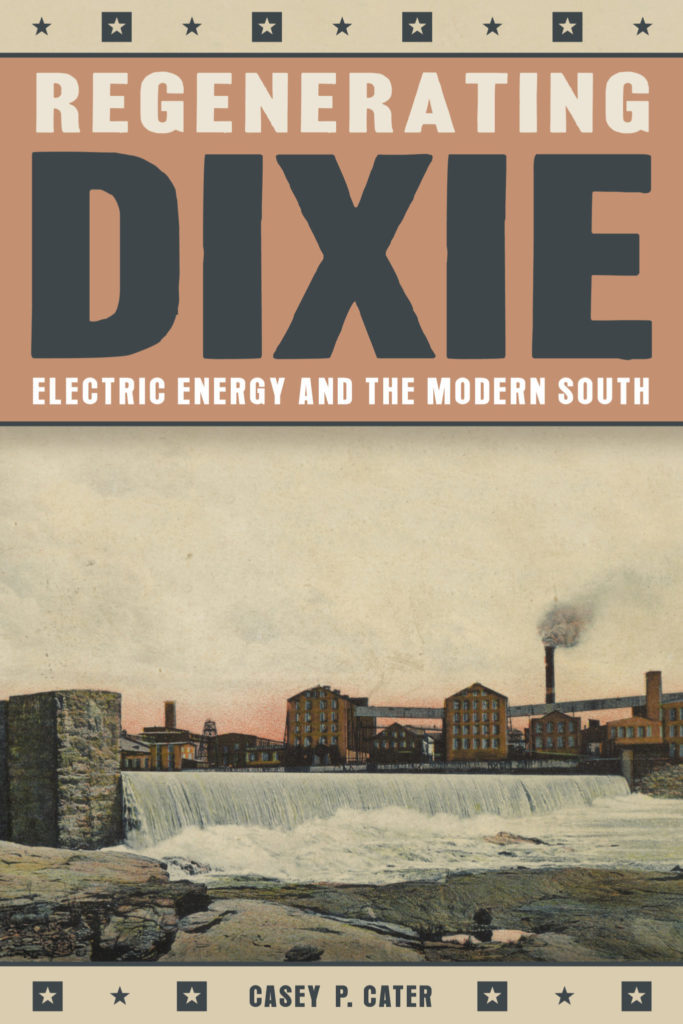

In his new book Regenerating Dixie: Electric Energy and the Modern South (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019), Casey P. Cater suggests that since “electric energy formed the material basis for the regimes of industrial and consumer capitalism that structured social hierarchies and daily life . . . without an accounting of electricity’s career, we remain unable to fully understand the modern South” (6).

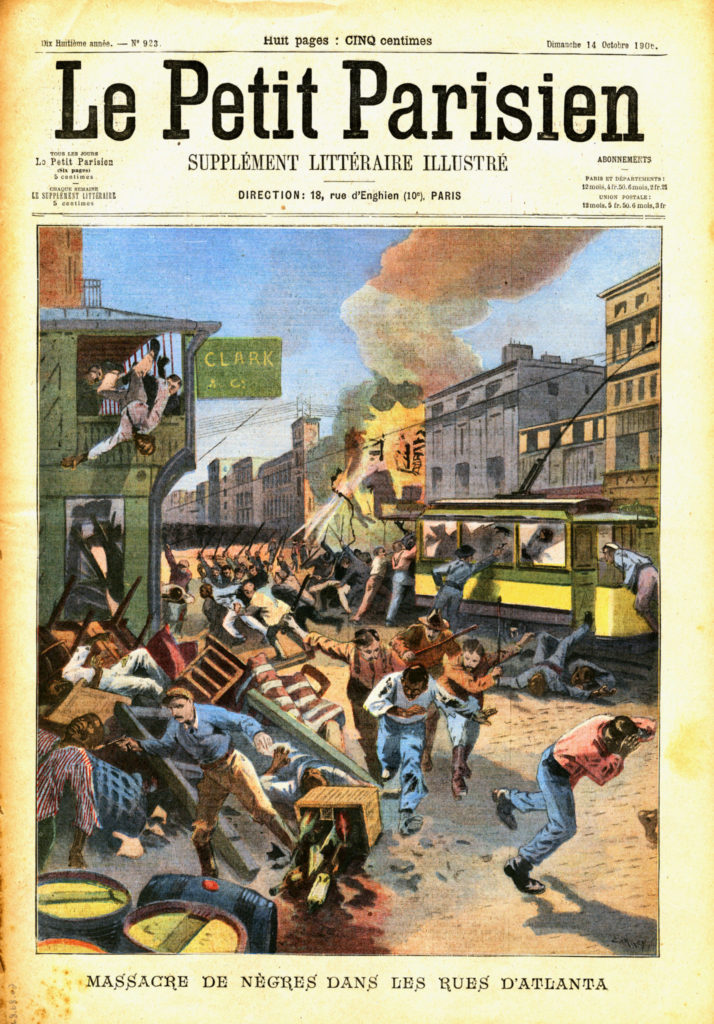

Cater also notes that “no state more than Georgia and no city more than Atlanta embodied the New South ethos” (6). For this reason, his narrative regularly examines developments in Atlanta to illuminate the often unexpected ways in which “electricity became a conduit for defining life in the modernizing, urban South” (54). In this excerpt, drawn from the book’s second chapter, Cater recounts how the local electric company’s streetcars became a central site of conflict over race relations in turn of the century Atlanta, playing an often ignored role in the lead up to the city’s infamous 1906 riots.

Excerpted from Regenerating Dixie: Electric Energy and the Modern South by Casey P. Cater. Copyright © 2019 University of Pittsburgh Press. Used with permission of the publisher, University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved.

The street car is an excellent place for observing the points of human contact between the races . . . in almost no other relationship do the races come together, physically, on anything like a common footing. In their homes and in ordinary employment, they meet as master and servant; but in the street cars they touch as free citizens, each paying for the right to ride, the white not in a place of command, the Negro without an obligation of servitude. Street-car relationships are, therefore, symbolic of the new conditions.

— Ray Stannard Baker, Following the Color Line (1908)1

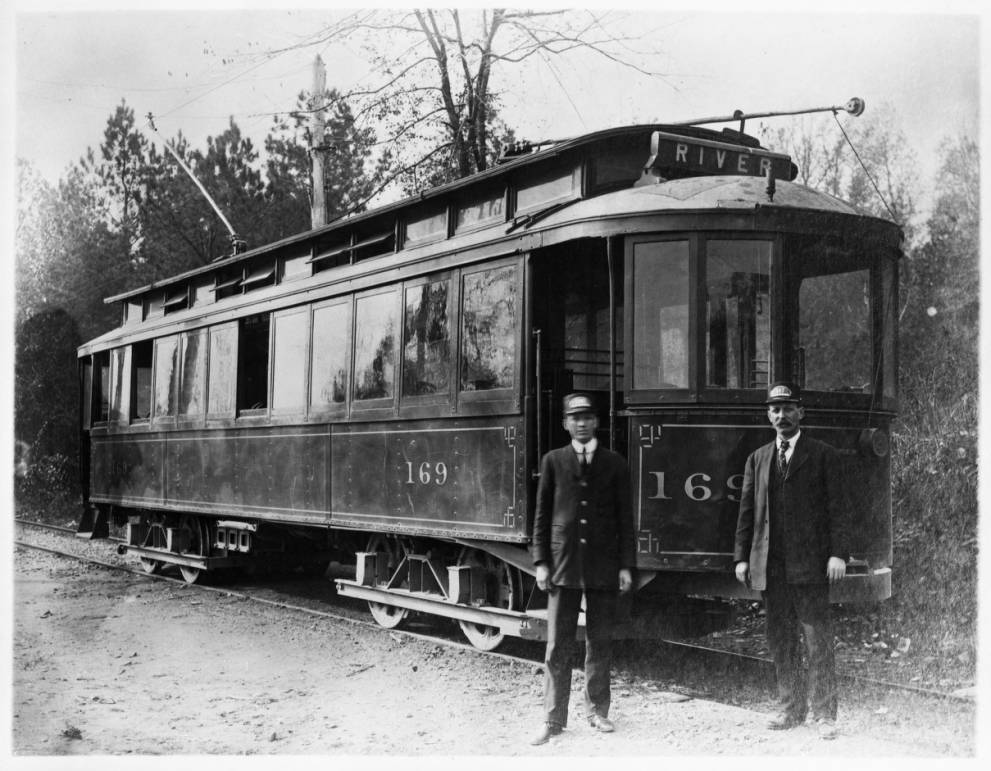

If most dreams for – and lived realities of – the New South’s future applied primarily to whites, African Americans too saw in the electrified city prospects for a better life. This was especially true of the streetcar systems whisking passengers across cities in Dixie like Atlanta. Electric streetcars had become not only the core of the southern utility industry little more than a decade after their introduction but critical features of urban life as well.

To be sure, readily accessible mass transit made city life more convenient for all citizens, but African Americans as much as any demographic took advantage of this new amenity, often constituting large proportions, and sometimes majorities, of ridership despite the passage of the first Jim Crow laws. After the US Supreme Court sanctioned privately administered segregation in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883, laws for segregated rail travel appeared steadily but unevenly across the South. In many instances, however, these edicts received only half-hearted enforcement. In Georgia’s case the law’s very language, which outsourced police power over privately administered urban mass transit to streetcar conductors, allowed trolley companies to avoid rigid adherence to Jim Crow seating, the application of which electric utilities often found overly burdensome. The Georgia statute, serving as a model for other southern states after its passage in 1891, required streetcar conductors to “separate the white and colored races as much as practicable,” which gave broad discretion to streetcar employees and often meant only that white passengers boarded through the front entrance and black passengers entered through the rear doors.2 In most places across the South, even after Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), there was no clear delineation of who was supposed to sit where: seats on trolleys – front, back, or middle – generally went to whoever boarded first. Just like white southerners, African Americans of all classes rode to work, church, shops, and places of entertainment in the racially murky terrain inside southern streetcars.3

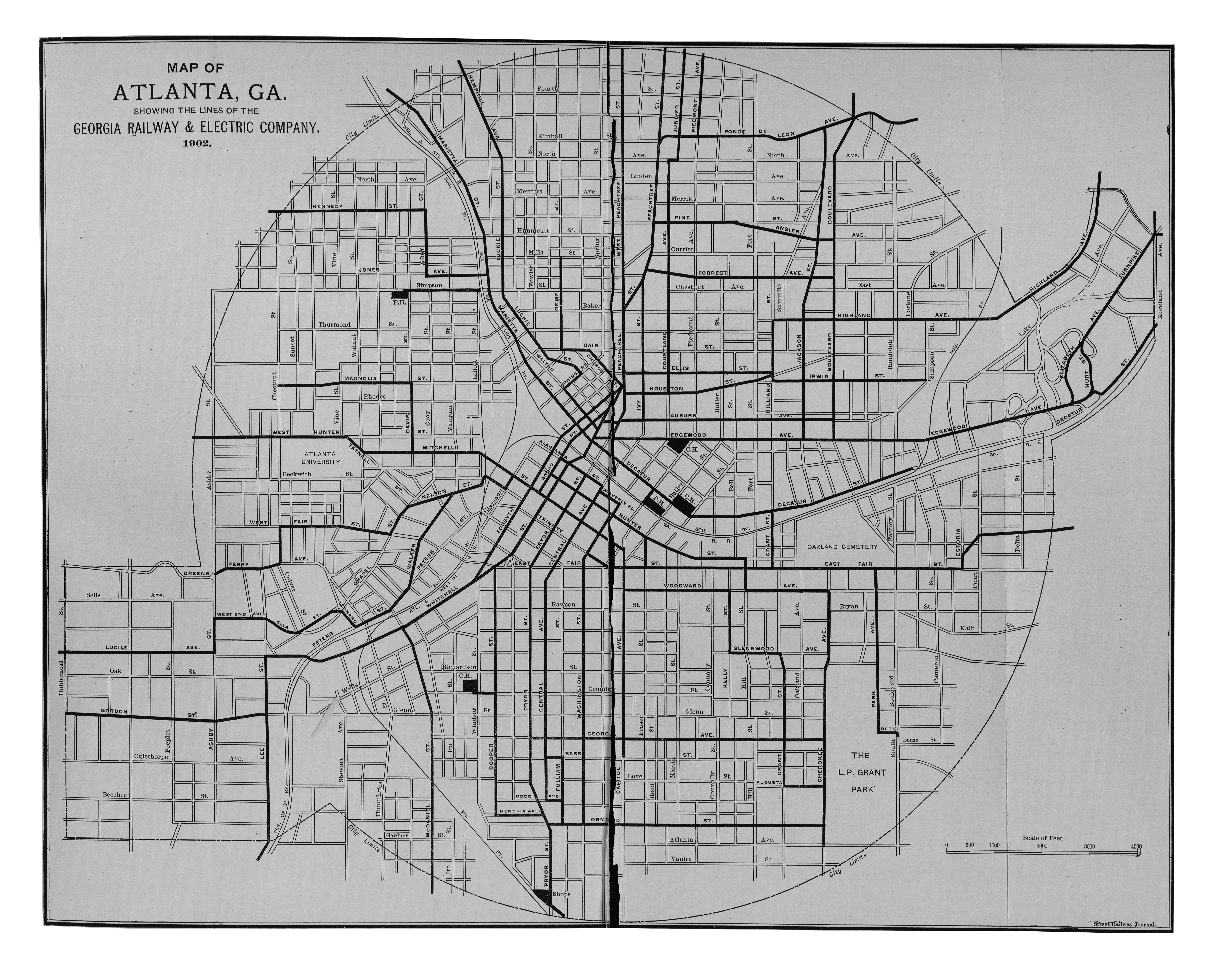

African Americans’ ability to ride trolleys without strict rules for separate seating derived from two interrelated realities: the financial demands of the streetcar business and black activism. Electric lighting companies emerged in the early 1880s and oversaw the construction of infrastructure for illuminating city streets. For profit-seeking lighting company managers, the sunk costs in electrical equipment required the most frequent usage possible, but early electric lamps generally operated only from evening to sunrise. When the electric streetcar became viable by the late 1880s, lighting companies often supplied the power: trolley passengers activated the capital otherwise lying idle for half of every day. As lighting and streetcar companies grew, so did their capital outlays. Power company owners quickly realized that increasingly large investments made economies of scale crucial. By the twentieth century’s dawn that realization not only confirmed that trolley companies must accept every fare-paying passenger possible but that corporate consolidation would be advantageous. In cities across the South and the nation, the years after 1900 saw lighting and streetcar firms merge into city-dominating, monopolistic utilities.4

Black activism intersected with these financial imperatives. Through various acts of resistance from the 1890s to the 1910s, black southerners demanded equal treatment on streetcars without the ignominy of screens, assigned seats, or other devices to physically divide the races. Such potential indignities provoked black southerners to speak publicly against attempts to relegate them to second-class citizenship, testifying to the significance they placed on the symbolic and material freedom of movement across the cities where they lived and worked. An 1896 editorial condemned an (ultimately failed) early post-Plessy Atlanta edict that would have forced black passengers to the last two rows of streetcars as “the most disgraceful decision ever rendered.”5 The writer reminded readers that African Americans had “spent enough money riding on the street cars in Georgia to own a line in the state,” intimating that by withholding their fares, black southerners could force trolley line managers to compromise.6

African Americans did just that, backing their condemnations of Jim Crow with effective protests. In southern cities including Atlanta, Jacksonville, Mobile, New Orleans, Richmond, and Savannah, both working- and middle-class African Americans participated in boycotts against trolley companies that attempted to implement Jim Crow.7 These actions posed a significant threat to electric utilities as streetcar traffic accounted for a substantial proportion of power companies’ earnings. Across the United States at the turn of the century, trolley fare receipts amounted to half of electric utilities’ revenues. For Atlanta’s Georgia Railway and Electric Company (GREC), which by 1902 controlled the city’s entire mass transit system, streetcar fare accounted for an outsized 70 percent of total income; one estimate claimed that a 1900 boycott in Atlanta cost trolley companies $5,000 per month.8 Street railway operators thus exhibited great sensitivity to even modest dips in streetcar revenue. In response to the fear that boycotts would jeopardize annual dividend payments, trolley companies worked to negotiate a middle ground between white calls for complete racial separation and African American demands for equal treatment. Though power companies sabotaged boycotts and ultimately sided with a social order grounded in white supremacy, seating arrangements on southern street-cars, particularly in Atlanta, remained relatively fluid for decades to come.9

The influence that electrified urban life in the New South afforded African Americans in their pursuit of equal rights served as a source of immediate anxiety for white southerners, but it portended broader, graver changes as well. African American agency on streetcars fueled fears that white people’s ostensible historical position as a superior racial group, and moreover their place in the American democratic polity, was in jeopardy.10 Many whites held that the equality they perceived on streetcars both symbolized and contributed to a larger, horrific inversion of the southern racial hierarchy, an inversion reminiscent of the one they purportedly witnessed in Reconstruction: blacks were becoming superior, whites were becoming subordinate.11 In the words of a Mrs. George Ball, ordinary white southerners, especially women riding alone on streetcars, had been forced “to quietly submit . . . to the domination of the negro” in the New South – a situation that would not be tenable for long.12 Moreover, that any African Americans could take advantage of mass transit systems while white workers often struggled to afford a ride – and, indeed, both black and white working-class people often walked – added severe insult to the perceived social injuries whites endured daily on Atlanta’s streetcars.13

For frustrated white Atlantans, the reason Jim Crow laws did not effectively mandate full racial separation was that corporate managers and New South proponents valued profits above all else. Despite signs of growing racial conflict on streetcars across 1905 and 1906, according to a scandalized Atlanta citizen, who identified herself only as “E.K.F.” in letters to both the Atlanta Constitution and Atlanta Georgian, GREC’s executives simply had no desire to enforce segregated seating.14 To do so would only reduce revenues for the company and dividends for stockholders. As she sardonically wrote to the Atlanta Georgian in September 1906,

The ladies and children must continue to be crowded into the street cars with the negroes because the street car company is too poor to furnish separate cars, for if they did what would become of the watered stock? 15

The populist leader and white supremacist firebrand Tom Watson held the same opinion. The love of profit above all else, he penned in 1906, had seen southern interests invite northern capital to Dixie with the disastrous result that women and children had been enslaved to an urban-industrial machine that “is grinding up their tender limbs into dividends.”16

For those in agreement with E.K.F. and Watson, ravenous corporations could only force white southerners into “bestial degradation” under the protection of New South–oriented Democrats who kept themselves in power thanks to a Faustian bargain. Pressing this line of thinking was the Atlanta Journal, whose publisher, Hoke Smith, echoed such sentiments while running for governor in 1906. According to Smith’s paper, New South Democrats had not only “perpetuate[d] the negro’s . . . political power” to both stay in office and ensure a steady flow of outside investments to the region, but disfranchised working whites as punishment for the Populist revolt.17 This point played on growing white resentments with the New South project. Of course by the turn of the century black voting rates across the South were reduced to negligible levels, but disfranchisement measures after 1890 – including poll taxes, property requirements, and literacy tests – saw voting rates for working whites steeply decline as well. Whereas about 75 percent of adult white men regularly voted through the early 1890s South, only 15 to 30 percent did so after 1900.18 The consequences of this unholy deal, many whites seemed to agree, materialized in the New South’s daily exchanges where Atlantans shuddered under a “reign of terror” in which haughty black men frequently flaunted their status, even to the point of violent assaults, on GREC’s streetcars.19

To counter this trend, wrote an Atlanta minister, white men must act as one to demand change and lead “a great revolt against” a corporate-political machine whose love of money had sullied Dixie with “negro domination.” If the call for white “reconquest” through reform went unanswered, the Atlanta Georgian chillingly predicted in early September 1906, the city’s white sons would rise in violent reprisals against their New South oppressors.20 It quickly became apparent, however, that legislative action could not possibly come soon enough, even if GREC president Preston Arkwright tried to defuse mounting tensions in early September by publicly stating that he and his company held the “same sentiment on the race question as all other southern people.”21 Referencing the inseparable (if largely imagined) issues of white political impotence, black political ascendancy, and ruinous corporate domination, the Georgian warned GREC and the city’s Democratic establishment that, in a twisted adaptation of Proverbs 15:1,22 By late September 1906, after a summer filled with alleged streetcar improprieties and black-on-white rape, Atlanta’s white men made it clear that they no longer had faith that the city’s political and corporate leaders would lend considerate hearing to calls for swift reform.

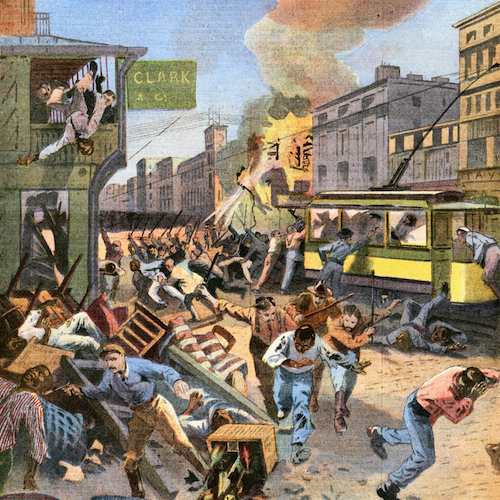

At about half past 10:00 p.m. on Saturday, September 22, 1906, GREC’s 207 car arrived at the busy intersection of Peachtree and Marietta Streets, where as many as eleven thousand angry whites had gathered – following several reported black-on-white sexual assaults earlier that day – to bring the “reign of terror” to a decisive and bloody end. Noticing that the 207 carried both black men and white women, the mob pounced. Not simply boarding the trolley, the horde disabled the car, smashed its windows, and ripped open its doors before viciously bludgeoning at least three black men to death and severely wounding several other men, women, and children. Moments later another GREC trolley passed through the same intersection. Both the car and the passengers inside suffered the same fate as the 207. Within three days, hundreds of people had suffered injuries and at least sixty African Americans and ten whites had been killed in the Atlanta Race Riot. In addition rioters damaged more than twenty streetcars on the evening of September 22 alone.23 White rioters in turn-of-the-century Atlanta were not simply sating their racist bloodlust by murdering African Americans in the streets and on streetcars. They were also rebelling against what they believed treacherous New South leaders had foisted on them: corporate ruination of Dixie humiliatingly experienced as “negro domination” in the everyday exchanges of urban-industrial life.

In the wake of the 1906 riot, a set of demagogic populists who claimed to speak for working-class whites emerged to argue that the New South’s redemption from the chaos of corporate-enabled “negro domination” would be found in public control over corporate activity. Such control, they insisted, could truly be achieved only if realized in concert with African American disfranchisement and the expansion of white male democracy – critically important issues given that, for the first two decades of its career, electricity appeared to be a fundamentally undemocratic enterprise. Because of the technical expertise, managerial sophistication, and outsized capital investment required to establish and maintain electric power businesses, ordinary people seemed to have had little say in utility operations and policies.24 By the twentieth century’s dawn, especially within the context of the push for greater white male political participation, African American exclusion, and corporate regulation, many southerners began to agree that electricity’s management should be a democratic process and acted to make it so, at least for white men. The resulting movement, a campaign not for regulation but for municipal ownership of electric utilities, drew on the abortive Populist crusade of the 1890s and made an indelible mark on electrification’s path in the New South’s capital.

Learn more about the racialized movement for municipal ownership of the electric company and streetcars in Atlanta elsewhere in Chapter 2. Casey P. Cater’s Regenerating Dixie: Electric Energy and the Modern South is available now from the University of Pittsburgh Press.

Citation: Cater, Casey P.. “Electrifying Race Relations: Atlanta’s Streetcars and the 1906 Race Riots.” Atlanta Studies. May 14, 2019. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20190514.

Casey P. Cater is an energy historian from Atlanta. He completed his PhD at Georgia State University in 2016. He was a 2014-15 IEEE Life Members’ Fellow in Electrical History and a 2015-16 Lemelson Center/National Museum of American History Fellow at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC.

Notes

- Ray Stannard Baker, Following the Color Line: An Account of Negro Citizenship in the American Democracy (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1908), 30.[↩]

- Railroad Commission of Georgia, The Report of the Railroad Commission of Georgia (Atlanta: Franklin-Turner Company, 1908), 98, emphasis added.[↩]

- Blair L. M. Kelley, Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Age of Plessy v. Ferguson (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 33–4, 88–91; Gregory Mixon, The Atlanta Riot: Race, Class, and Violence in a New South City (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005), 38–43, 129–30.[↩]

- Paul W. Hirt, Wired Northwest: The History of Electric Power, 1870s–1970s (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012), 34−5.[↩]

- Untitled editorial, Southwestern Christian Advocate, August 20, 1896.[↩]

- Ibid.; also see: August Meier and Elliot Rudwick, Along the Color Line: Explorations in the Black Experience (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1976), 270–1.[↩]

- Meier and Rudwick, Along the Color Line, 268–9.[↩]

- Christopher F. Jones, Routes of Power: Energy and Modern America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 167; Wade H. Wright, History of the Georgia Power Company, 1855–1956 (Atlanta: Georgia Power Company, 1957), 84; Jean Martin, Mule to MARTA (Atlanta: Atlanta History Center, 1977), 1:17.[↩]

- Kelley, Right to Ride, 2–6, 185–7; Ronald H. Bayor, Race and the Shaping of Twentieth-Century Atlanta (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 188; Mixon, Atlanta Riot, 35–6.[↩]

- See Joel Olson, The Abolition of White Democracy (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), xv–xvii.[↩]

- David Fort Godshalk, Veiled Visions: The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot and the Reshaping of American Race Relations (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 25–32; Stephen Kantrowitz, Ben Tillman and the Reconstruction of White Supremacy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 259–61.[↩]

- Mrs. Geo. C. Ball, “The Race Problem from a Domestic Point of View,” Atlanta Georgian, September 8, 1906.[↩]

- See Edward L. Ayers, Promise of the New South: Life after Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 136–40; also see David E. Nye, Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1888–1940 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990), 96–7.[↩]

- “Letters from the People: Separate Cars for Negroes,” Atlanta Constitution, July 19, 1905; “Trail Cars for the Negroes,” Atlanta Georgian, September 8, 1906.[↩]

- “Trail Cars for the Negroes.”[↩]

- Tom Watson, “Down in Georgia,” Tom Watson’s Magazine 4 (March 1906): 1.[↩]

- “The Nigger in the Woodpile,” Atlanta Journal, November 10, 1905.[↩]

- Ayers, Promise of the New South, 309.[↩]

- “Letters from Georgian Readers, with Especial Reference to the Race Question: The Inevitable Remedy,” Atlanta Georgian, September 11, 1906; Mixon, Atlanta Riot, 73–81.[↩]

- Rev. Sam Jones quoted in Mixon, Atlanta Riot, 67.[↩]

- Martin, Mule to MARTA, 2:22.[↩]

- “The Spirit of Our Corporations,” Atlanta Georgian, September 10, 1906.[↩]

- “Attack by Mob on Street Cars,” Atlanta Constitution, September 23, 1906; Godshalk, Veiled Visions, 91–3, 107–8; Mixon, Atlanta Riot; and Joel Williamson, Crucible of Race: Black-White Relations in the American South since Emancipation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 209–23. [↩]

- See Hirt, Wired Northwest, 21.[↩]