On September 11, 1963, James V. Carmichael, president of Scripto, Inc., stood before his workforce of nearly 1,000 employees, most of whom were African American women, to argue against a vote for unionization in the Atlanta factory that made mechanical pencils, pens, and cigarette lighters.

Carmichael, a white businessman, attorney, and civic leader, boasted about the company’s history of creating jobs for black Atlantans for more than thirty years. He claimed that he was “one of the truest friends the Negro has ever had in Georgia and in the entire South” and insisted that “Negroes have not been made to bear the stigma of second-class citizenship during their employment with Scripto.”1 “I have known for many years what the Negro really wants!,” he told his employees. “What the Negro really wants is equal economic opportunities number one.”2

While Carmichael preached equal opportunity, Scripto’s black workers instead saw dead ends that trapped them in low-wage jobs with little chance of gaining economic autonomy. They voted to organize with the International Chemical Workers Union (ICWU) a few days later. By the winter of 1964, Scripto employees were marching in the streets, with the support and presence of Martin Luther King Jr., demanding an end to the racial discrimination that kept all but six black women in unskilled positions at the factory.3Historians tend to mention the strike only in the context of King’s participation, particularly as it marked his shift towards explicitly uniting labor and civil rights activism. But the Scripto strike also reflected the deep tradition of labor activism among black working-class women in Atlanta that long predated the mass movement phase of the civil rights struggle. As historian Tera Hunter has recounted, for example, Atlanta’s black washerwomen were organizing even in the late nineteenth century to fight for a livable wage and control over their working conditions.4 And black women workers at the Scripto plant had previously tried to organize in 1940, 1946, and 1953. Within this broader context, the 1964 Scripto strike looks less like a product of the midcentury civil rights movements and more like a victory in the long fight for black women’s economic rights in Atlanta.

Moreover, a close examination of the labor history at the Scripto factory across three decades reveals the way the 1964 strike offered a specific rebuttal to Carmichael’s well-intentioned yet paternalistic management practices that had shaped the company and Atlanta’s racial hierarchies since the 1940s. Uncovering that history provides a richer appreciation of why the Scripto workers took to the picket line in 1964 and how those workers understood the differences between economic opportunity and economic autonomy. I explore these themes further in my chapter “Pens, Planes, and Politics: How Race and Labor Practices Shaped Postwar Atlanta” in the new book Reconsidering Southern Labor History. In the chapter, I place the experience of Scripto’s employees in dialogue with the history of unionization and government oversight at the Lockheed plant in Marietta, which Carmichael also managed for a short time. This comparative history of two factories reveals how race, gender, defense spending, and government intervention shaped different sectors of southern industry that kept Scripto’s black women workers at the bottom of the Sunbelt political economy.

The Business and Politics of James V. Carmichael

Although he is less often remembered today than other white business leaders like Asa Candler or Robert Woodruff, Carmichael shaped the Atlanta metropolitan region like few others in the twentieth century. His influence remains particularly notable in Cobb County. Carmichael helped turn his native Marietta into a center for aircraft manufacturing during World War II as assistant general manager of the Bell Bomber factory. He continued to help build the area’s aircraft industry when he convinced the Lockheed Corporation to locate its southern manufacturing plant in Marietta. He then served as the factory’s general manager during its first year of production while taking a leave of absence from Scripto from 1951–52.Carmichael also pursued power through elected office. He served in the state’s General Assembly in the 1930s and ran for governor in 1946 against white supremacist demagogue Eugene Talmadge, pioneering the kind of racial moderation sometimes described as Atlanta exceptionalism and often associated with figures like Mayor William B. Hartsfield. On May 11, 1946, he took to the airwaves of Atlanta radio station WSB to attack Talmadge’s “broken promises and ranting dictatorship” and warn of the economic repercussions of the election, declaring:

No one is going to invest money in industry when you have in the governor’s office a man who is continually stirring up race and class hatred and creating unrest in labor’s ranks.5

Carmichael’s message resonated with the white Georgians who were able to vote in the Democratic primary. While he received the most votes, he lost the race because Talmadge won a majority of counties, a feature of Georgia’s idiosyncratic election laws at the time that were designed to stifle the political power of urban voters.6

Despite his better-known contributions to Cobb County, Carmichael spent the longest tenure of his wide-ranging career in downtown Atlanta as president of Scripto, Inc. from 1947 to 1964. The Scripto factory was located in a gated complex that took up an entire block on what is now John Wesley Dobbs Avenue, not far from the Ebenezer Baptist Church and the then-thriving African American business district located along Auburn Avenue. African American women comprised approximately 85 percent of Scripto’s workforce, in part because industrial work offered an escape from demeaning domestic service jobs in white households. Scripto employed so many working-class black women that white women bemoaned how “you couldn’t get a good cook in Atlanta.”7Carmichael considered himself a benevolent employer and prided himself on creating jobs for black Atlantans. He also believed that such benevolence precluded the need for union representation and expressed opposition towards organized labor. In a speech delivered at Emory University – his alma mater – in 1952, Carmichael confessed that business owners had exploited their workforce in years past and recognized that unions offered a way for workers to fight against those abuses. Yet Carmichael also suggested that union members now followed their leaders “blindly.” In his view, “enlightened management” could avoid a union’s interference with a boss’s prerogative and oversight from the National Labor Relations Board by simply paying a fair wage.

Carmichael elaborated on his strategies for maintaining a productive workforce in a profile of him that appeared in the September 1958 edition of Management Methods magazine. He drew the attention of the business journal for expanding Scripto’s sales reach into one hundred foreign nations and establishing production centers in Canada, England, Southern Rhodesia, and Australia, successes that helped establish Atlanta as a center of global capitalism. Without mentioning the fact that African American women comprised the majority of his workforce, Carmichael bragged to the magazine that “the biggest advantage” to doing business in the South “is a plentiful supply of a very satisfactory type of labor. Most of the people here in the South have a heritage that goes back over several generations.”8 He believed that “These roots make for a very stable type of employee. In our Scripto plant, absenteeism is practically nil; turnover is practically nil. And our people give us a full day’s work.”9 Carmichael knew black people, he implied to the magazine writers, and his guidance kept the Scripto workforce satisfied, effective, and non-unionized.

Organizing Scripto in the 1940s and 1950s

The rosy picture of Scripto employment that Carmichael offered in his 1958 profile ignored the long history of labor activism at the plant. Attempts to organize workers at the Scripto factory dated back to 1940, when the United Steelworkers of America (USW) first tried to unionize the company’s majority black workforce. That effort failed, and the USW organizer notably blamed the few white workers at Scripto for undercutting support for the union.10 But the USW tried again six years later and gained the workers’ approval in February 1946.11

The USW won in 1946, in part, because it enjoyed the support of black Atlanta’s religious leaders, including Martin Luther King Sr. Many of Scripto’s black employees attended Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King pastored. USW director W. H. Crawford wrote to King, expressing how the pastor’s participation delivered the support necessary to sway black workers into voting to organize.12 Scripto refused to negotiate a contract despite worker approval of the USW, and Crawford called for a strike in October 1946. More than five hundred of Scripto’s six hundred black employees took to the picket line in a show of racial and union solidarity.13The strike persisted for six months in the face of intimidation from the Atlanta Police Department, some of whom were known members of the Ku Klux Klan.14 Scripto even hired members of the force in their off-duty time to shuttle strikebreakers in and out of the factory.15 In spite of the company’s tactics, four hundred workers remained on the picket line when the USW finally called for an end to the strike in March 1947. Scripto only permitted nineteen of those workers to return to their jobs, and the USW filed charges against the company.16 Nonetheless, when the National Labor Relations Board delivered its ruling on the alleged violations, it found the company free of wrongdoing.17

After Carmichael took over as president of Scripto in 1947, he clashed with a subsequent attempt to unionize the company’s workers at its ordnance plant in 1953. Once again, the company fired all the women who had campaigned for the union. Scripto closed its ordnance division altogether in 1954 following the end of the Korean War.18

Labor Rights and Civil Rights at Scripto in the 1960s

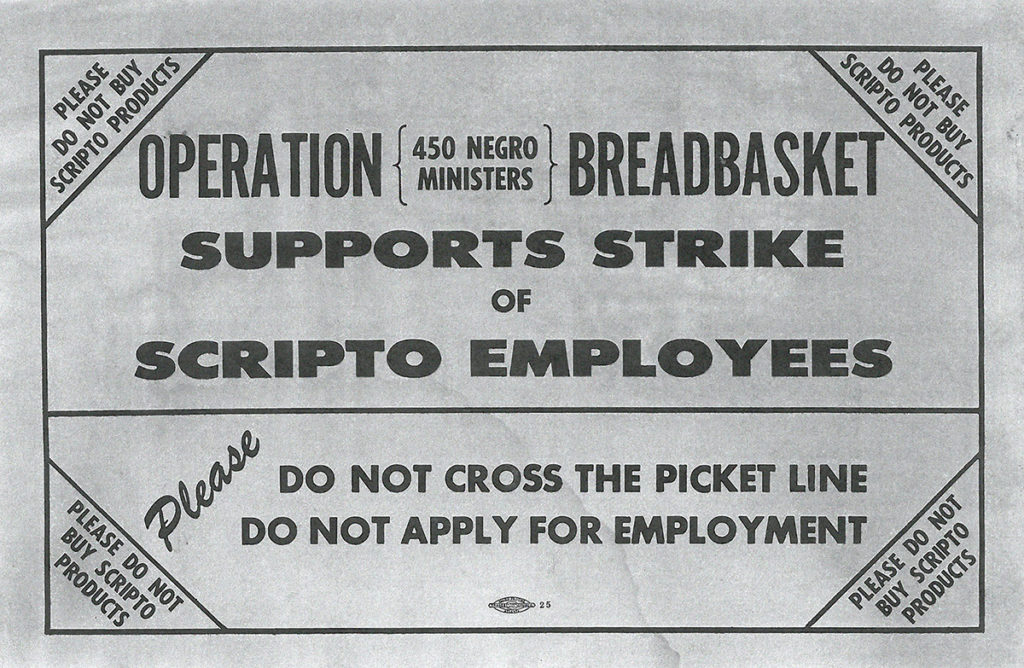

When Carmichael stood before his employees in September 1963 and discouraged their approval of the ICWU, Scripto’s workers knew full well the benefits and risks involved with unionization. These workers held management’s promises in one hand, the prospect of collective bargaining in the other, and chose to cast their lot with the union.In November 1964, members of Scripto’s new ICWU chapter called for a strike, demanding increased wages and an end to racial discrimination. Seven hundred workers, the majority of them women, took to the streets. At a rally for the strikers in early December, minister and civil rights leader C. T. Vivian told the local black press that,

If Atlanta is a city too busy to hate, why can’t she get busy enough to abandon old labor policies? . . . Labor’s demands are our demands.19

Likewise, when Martin Luther King Jr. joined the strikers on the picket line later that month, he told the press that economic inequality had always provided the basis of racial segregation and that “the civil rights movement and the labor movement must stick together” to fight white supremacy.20 Due to a combination of falling profits and the chronic health problems Carmichael sustained from a car accident in his youth, Scripto replaced the long-time boss in 1964 with Carl Singer, a northerner with experience in the mattress industry.21 Late in December, King and Singer held a series of secret meetings that delivered an end to the strike on January 9, 1965, along with union recognition, a Christmas bonus, and a four-cent raise. However, these behind-the-scenes actions also brought criticism from the ICWU for settling too soon.22

Of course, the Scripto workers already understood Vivian and King’s argument about the intertwined relationship of race and labor before the strike even began. Black women, in particular, knew how race and gender trapped them in low-wage positions. Since the 1880s, Atlanta’s working-class black women had organized for their economic rights, and they would continue to do so into the 1970s via organizations like the National Domestic Workers Union of America.23 For though employment at Scripto offered a way out of domestic service for hundreds of black women, these women also knew that economic opportunity did not necessarily create a path to economic autonomy. In 1964, the Scripto workers turned to the union as a bulwark against the power of capital and the paternalistic control of white bosses in the Atlanta labor market.

Citation: Thompson, Joseph M.. “The Scripto Strikes: James V. Carmichael and Black Women’s Labor Organizing in Downtown Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. September 04, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20180904.

Notes

- Carmichael remarks, September 11, 1963, James Vinson Carmichael papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University (hereafter Carmichael papers).[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Hartwell and Susan Hooper, “The Scripto Strike: Martin Luther King, Jr.’s ‘Valley of Problems’ in Atlanta, 1964–1965,” Atlanta History: A Journal of Georgia and the South 43, no. 3 (Fall 1999): 5–34.[↩]

- Tera W. Hunter, To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997).[↩]

- WSB Broadcast, 11 May 1946, Carmichael Papers.[↩]

- Thomas Allan Scott, Cobb County, Georgia and the Origins of the Suburban South: A Twentieth Century History (Marietta, GA: Cobb Landmarks and Historical Society, 2003), 207; Scott E. Buchanan, “County Unit System,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/counties-cities-neighborhoods/county-unit-system.[↩]

- Quoted in Hooper and Hooper, “The Scripto Strike,” 8.[↩]

- Ibid., 83.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Charles Mathias to the White Employees of Scripto Manufacturing, Inc., October 14, 1946, Correspondence, Scripto Manufacturing Co., 1946-1952, United Steelworkers of America, District 35 Records, 1940–1974, L1975-21, Southern Labor Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University, Atlanta (hereafter USW records).[↩]

- United States of American, Before the National Labor Relations Board, Exceptions to Report on Objections, Case No. 10-R-1567 and Case No. 10-R-1610, USW records.[↩]

- W. H. Crawford to Martin Luther King Sr., February 25, 1946, USW records.[↩]

- W. H. Crawford to USW District Directors, October 24, 1946, Correspondence, Scripto Manufacturing Co., 1946–1952, USW records.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Report on Conferences with Scripto Plant, USW records.[↩]

- A. C. Joy to Charles C. Mathias, July 8, 1947, USW records.[↩]

- “Comparison of Sales 1947 thru 1962,” Carmichael papers.[↩]

- Quoted in Hooper and Hooper, “The Scripto Strike,” 12.[↩]

- G.S. Carlson, “Must Fight for Better Jobs, King Tells 250 Scripto Strikers,” Atlanta Constitution, December 21, 1964, 24.[↩]

- Hooper and Hooper, “The Scripto Strike,” 23.[↩]

- Hooper and Hooper, “The Scripto Strike,” 23, 26.[↩]

- Hunter, To ‘Joy My Freedom; Premilla Nadasen, “Power, Intimacy, and Contestation: Dorothy Bolden and Domestic Worker Organizing in Atlanta in the 1960s,” in Intimate Labors: Cultures, Technologies, And the Poltiics of Care, eds. Eileen Boris, and Rhacel Salazar Parreñas, (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010), 204–16.[↩]