Citation: Davis, Marni. “Closing the “Open Door”.” Atlanta Studies. December 13, 2016. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20161213

We publish Charles Steffen’s account of downtown Atlanta’s Skid Row at a lamentably appropriate moment. This summer, the Open Door Community announced that after 35 years of providing food, advocacy, and spiritual solace to poor and homeless Atlantans, they don’t have the personnel or resources to maintain their facility at 910 Ponce de Leon Avenue and must close down early next year. Steffen’s history of Skid Row’s demise in the 1980s repeats itself today, but a couple miles to the northeast. Once again, urban development and municipal policy are transforming the city; each time, spaces that Atlanta’s neediest have come to rely upon – places where they might access resources and a sense of community – are erased.

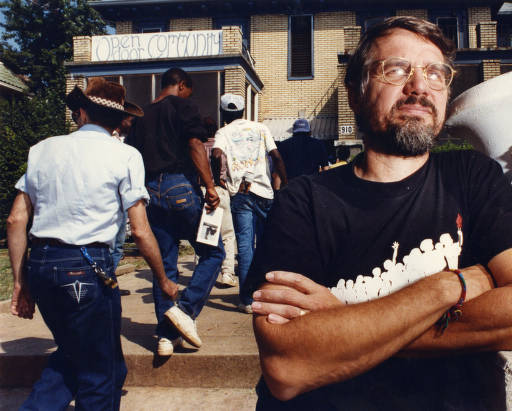

Open Door’s announcement compelled me to track down the 2004 article in Creative Loafing where I’d first learned about their history and mission. I had noticed the building in passing: the hand-painted welcome sign above the entrance, the dark old apartment house in disrepair, the front yard that bustled with activity around mealtimes. It appeared anomalous to its environment, a stretch of Ponce that was anchored by Urban Outfitters on one end and Whole Foods on the other. Poncey Highlands was still fairly shaggy, but it had been designated a “transitional” neighborhood since the 1970s. By the early aughts, even more development and upscale commerce seemed inevitable – well before the Beltline was much more than a proposition under study.

I learned from the Creative Loafing piece that Ed Loring and his wife Murphy Davis founded the Open Door ministry in 1981, after several years of doing similar work in the Lake Claire neighborhood. They were motivated by a mix of liberal evangelical Protestantism, radical Catholic Worker ideology, and an unrelenting critique of capitalism and racial injustice. They’d bought the house from a group that had used it as a women’s shelter, gathered several more like-minded couples to act as residential leadership, and served their first breakfast to anyone who needed it in 1982. They had been feeding and advocating for the poor ever since, invoking the Christian practice of “hospitality” – a philosophy that obligated them to offer not only sustenance, shelter, and assistance navigating the city’s social service bureaucracy, but dignity and unconditional friendship as well.

The Creative Loafing article was inspiring, but a quote from the rabbi at Chabad Intown, the Orthodox Jewish outreach center a few doors down, gave me particular pause. “It’s a negative for the neighborhood,” he declared, adding “when you feed someone, you don’t help them.” As a Jew, I was horrified: I’m as secular as can be, but the core ethical teachings of Judaism instruct us to identify with the poor and to treat them with compassion. Homelessness is a complicated problem, and there are legitimate debates about how best to alleviate it. But this rabbi’s easy evocation of trickle-down bromides suggested a level of complacency I could not abide. So I decided to offer my time to Open Door, an act I hoped would achieve some kind of Jewish karmic ballast.

For three years, twice a week, I served breakfast at sunrise, or gave out aspirin and heartburn chewables and other over-the-counter meds. Eventually, I was assigned to work on shower days. My post was behind the counter in a huge closet, where I distributed soap, towels, and clean clothes. Hygiene products, too, like deodorant and talcum powder. Feminine pads on women’s shower days. Dry socks, and shoes that fit. Quotidian things that are easy to take for granted when you can access them without effort. I came to appreciate the leadership’s practices: a general sense of fellow-feeling, combined with an organizational style that both rationalized and humanized waiting one’s turn for a meal and a shower. Mornings at Open Door were boisterous, but generally genial, and admirably efficient.

I got to know the regulars, whose stories were as varied as you would find in any random group. Some gave the impression of having consciously, actively chosen life on the street; I recognized a few habitués of Findley Plaza in Little Five Points. Others were pretty out of it, perhaps because they needed medications they couldn’t consistently access or were addicted to substances that loosened their grip. The traumas of homelessness worsened their instabilities, in some instances to a frightening degree. But plenty who ate at Open Door were on their way to work at jobs that paid penurious wages, or were elderly or disabled and lived semi-independently in assisted-living group homes around the neighborhood. And many of them were simply somewhere along the spectrum of down-on-their-luck: a job loss or a divorce, a chronic illness, eviction or car repossession, or they were ensnared in the judicial bureaucracy. Perhaps they or a family member had made an unfortunate financial decision, and the bottom had dropped out of their lives.

I recognized many of their problems and crises. Plenty of people I knew had gotten in trouble with the law, or endured mental illness and other medical emergencies, or run out of money, or had to abandon an apartment in a hurry. Bad health, bad choices and bad luck befall us all, sooner or later. But among my middle-class friends and acquaintances, family savings, insurance, and other resources were available to help them climb out of the hole they’d fallen or dug themselves into.

Open Door’s earliest visitors might have availed themselves of downtown’s single room occupancy buildings (SROs) and day labor centers, until they were pushed out by Underground Atlanta and the other efforts at commercial development chronicled in Steffen’s essay. Three decades later, Open Door’s leadership reports that their neighborhood – now defined by the Beltline, Ponce City Market, and soaring real estate values – is gentrified to a degree that “it has become an inhospitable space for the homeless poor.” The closure of the Open Door Community’s home means fewer beds and fewer meals for those who need them desperately; most tragically, it means one less space where the city’s needy will be treated with dignity.

The point here is not to romanticize homelessness, or to suggest that Skid Row and Open Door represent a civic ideal. Life on the street, or teetering on the edge of destitution, is soul-warping and dehumanizing and dangerous. And it would be outrageous to suggest (though some do) that all urban revitalization is bad, or that gentrification is inevitably immoral. But if every time a neighborhood improves, vulnerable locals at the economic margins are displaced, we’re doing this wrong.

Karen Beck Pooley is a Professor of Practice of Political Science and co-directs the Small Cities Lab at Lehigh University. She also serves as the Director of Research and Analytics at czb LLC, an urban planning and neighborhood revitalization consulting firm. She previously ran Allentown’s Redevelopment Authority and was a Deputy Director within New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. She has a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from Wellesley College, a Master of Urban Planning & Policy from New School University’s Milano Graduate School, and a Ph.D. in City Planning from the University of Pennsylvania.