Citation: Brock, Julia, Teresa Bramlette Reeves, and Kirstie Tepper. “Art and Activism in 1970s Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. October 4, 2016. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20161004

But, the seventies here bore the fruit of activist labor and economic growth of the 1950s and 1960s and also saw the deleterious effects of urban renewal, white flight, and the continuation of discriminatory housing policies. The city got its first truly biracial government and its first black mayor in 1973. In the same year, the Georgia General Assembly passed a new city charter that gave more voice to communities in city planning processes. Two years before that, voters approved the Metro Atlanta Rapid Transit System (MARTA), which increased mobility in the city. 1 For the first time in fifty years, African Americans from other parts of the country began to move to Atlanta (and other urban centers in the South) for economic opportunities. 2 At the same time, neighborhoods in the city remained segregated; communities reeled from the effects of displacement by interstates, stadiums, and housing developments; and a recession in the mid- and late-1970s threatened support for the coalitions built earlier in the decade.

Against this backdrop, a new, young art scene emerged—one that cannot be separated from the political, social, and economic structures of the city. 1970s Atlanta gave rise to a new energy for public support of the arts, and without this base the doughty organizations of our contemporary art scene might not have formed. The second half of the 1970s was an especially generative time for Atlanta arts due to a renewed activism among young artists, a plenitude of national arts funding, and the support of Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson’s administration. The result was an array of alternative art spaces, all created in the midst of a national recession, that supported experimental art practice and community-based work. Though severely hampered by the decimation of arts funding that came during Ronald Reagan’s presidency in the next decade, many of the arts and cultural organizations founded in the 1970s remain vital to Atlanta today: the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, Art Papers magazine, the city’s Office of Cultural Affairs, Seven Stages Theater, the Center for Puppetry Arts, WRFG, and the Atlanta Film Festival, for example. Moreover, the activism of the 1970s has parallels to recent history in the city’s art world, namely in the artist-initiated organizations that began in the late 2000s, in the midst of another recession.

In 2015, we began a project to document this scene, and particularly its women builders. The result is the ATLMaps site ATLas (Atlanta art scene), which explores 1970s Atlanta through the memories of eight women artists and/or art administrators. The site is a companion to the physical exhibition Forget Me Not, which was organized by the Zuckerman Museum of Art at Kennesaw State University and on display from August 22–December 6, 2015. Forget Me Not featured ten women whose work explores loss, repetition, ritual, and memory. Part of our inquiry extended to the loss of memory (perceived by us) surrounding the history of arts in Atlanta, and the desire to recover the 1970s scene through the voices of its women creators, though men certainly played a part. We began by interviewing women (biographies included below) who were instrumental in several grassroots organizations from this decade: the Atlanta Art Workers Coalition (1976), the Women’s Art Collective (1976), the Neighborhood Arts Center (1975), the Forrest Avenue Consortium (1976, later Nexus), Art Papers (1977; it began as the Atlanta Art Workers Coalition Newspaper), and Nexus Press (1977). 3 Narrators spoke to the funding sources, activities, and places important to the arts scene. We have plotted these narratives on ATLMaps; the women’s stories are framed and contextualized by maps from roughly the same era that visually divide Atlanta by race, class, and commercial interests. The map is not comprehensive but representative, rather, of what narrators remembered and considered important after forty years.

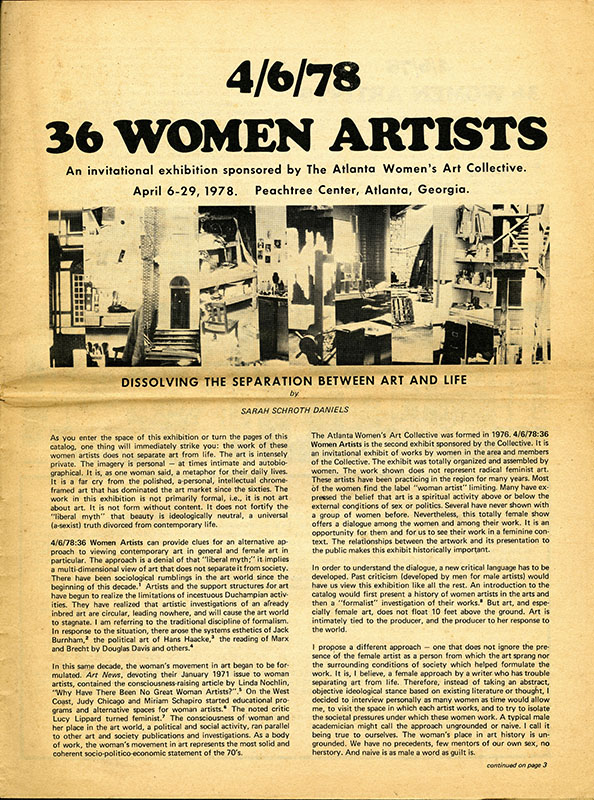

A strong current of activist energy infused the 1970s scene in Atlanta, as it did in other urban centers. JoAnne Paschall remembered that “artists at that time were . . . coming off of the avant-garde movements of the sixties, the post-World War stuff, and they were ready to take control over things as opposed to waiting for the art world to give them a nod.” That ‘nod’ might have come in the form of gallery representation or a coveted museum show, opportunities largely limited to white men. As Paschall notes, “the movements of the sixties opened things up a bit.” 4 Artists who identified with the women’s movement and the Black Power movement consciously upset art world conventions. In Atlanta, change came in the form of organization building. The Atlanta Art Workers Coalition (AAWC) operated as a union, offering alternative exhibition space, a workshop series, an insurance plan, and general advocacy for Atlanta artists. The Neighborhood Arts Center (NAC) was closely tied to the Black Arts movement of the 1960s and 70s, and offered gallery and studio space, performances, and free classes in visual arts, dance, theater, and music. 5 The Forrest Avenue Consortium (FAC) was another multi-arts facility that housed visual artists, a book press, photographers, and dancers. The Women’s Art Collective (WAC) was a consciously feminist organization that advocated for women artists and hosted exhibitions, workshops, and opportunities to network with women artists around the country.

Though the impetus of young artists created the scene, it was matched by support from the city’s leaders. All ATLas interviewees spoke to Maynard Jackson’s role in supporting Atlanta arts in the 1970s. Elected in 1973, Jackson, a lawyer and the grandson of Atlanta civil rights leader John Wesley Dobbs, became Atlanta’s first African American mayor. He served two terms in that role in the 1970s, and a third in the early 1990s. Jackson launched an internal campaign to include more black men and women in city administration and contracts and an external one to recast the city’s image as one of “Black-is-Bountiful,” according to one New York Times headline. 6 He was also a tremendous advocate for and lover of the arts, confessing at one arts-related conference that he had a “secret, lifelong desire to be Pavarotti” (his aunt, Mattiwilda Dobbs, was an opera singer). 7

Jackson created the Bureau of Cultural Affairs (BCA), the city’s programmatic and funding arm for the arts. Michael Lomax was head of the BCA in its beginning, and, then, when it was promoted to department status in 1979, future mayor Shirley Franklin led the organization. Jackson also established a “Mayor’s Week for the Arts” and held a monthly forum to bring arts organizations together. 8 He believed that a robust arts scene would solidify Atlanta’s growing reputation as an international city, but his comments at the time suggest that he made a connection between access to arts and human rights: “The arts need to be perceived as a necessity for life, particularly for the poor who are given so few options; the arts help give a larger vision of life.” 9

The BCA coordinated major cultural events for the city (the Free Jazz festival, a Georgia folklife festival) and had a budget from which it granted funds to support individual artists and arts organizations. It also managed funds that came from the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), created by Richard Nixon in 1973. 10 CETA, a jobs and training program, was another pillar of the 1970s art scene, in addition to Jackson and the creative animus of young artists. The national CETA office dispersed funds in block grants to be used, following guidelines and restrictions, as state and local municipalities saw fit. Though the majority of CETA funds went to short-term employment and job training in blue-collar and vocational work, some cities, including Atlanta, put artists on the government payroll. Almost all of the women interviewed for ATLas benefitted from CETA.

Though San Francisco can claim to be the first city to use CETA funding for the artists, Jackson and his administration were developing a similar program in Atlanta virtually simultaneously in 1975. Over the course of CETA’s life in cultural patronage (1975–1981), the city positioned 350 workers in “public service employment,” Title VI under CETA that granted eligibility to arts and cultural workers. 11 The BCA structured CETA employment in three categories: arts management, artists-in-residence, and technical support. The result was, for a time, richly staffed arts organizations and employed artists. As Julia A. Fenton noted, “The staff was paid for, their insurance was paid for, and you could get more staff than you knew what to do with because there were a lot of unemployed artists.” 12 In 1977, the Neighborhood Arts Center had thirty-six CETA employees, enough for the facility to offer a robust range of free classes to the surrounding community. 13 The Forrest Avenue Consortium, the WAC, and the AAWC all had staff positions paid for by the program, from gallery directors to administrative assistants and even janitors. Tom Cullen of the BCA argued that CETA funds built “an indigenous cultural life by stabilizing the artist’s community, by stemming the flow of artists to places like New York City.” 14 Alice Lovelace, a writer-in-residence at NAC, summarized that “CETA was everything.” 15

There were other important sources of funding as well, including the city, the Fulton County Arts Council, the Georgia Council for Arts and Humanities (now the Georgia Council for the Arts), and the Southern Arts Federation (now South Arts)—the latter two dispersed monies from a then well-funded National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). But CETA paid artist salaries and so organizations and artists coveted the positions. It was difficult for groups not to become reliant on these funds—not to become, as Laura Lieberman wrote at the time “CETA junkies.” 16 The competition for funding created divisions and tensions within the arts community, particularly when one group was perceived to be (or actually was) favored by the BCA. NAC and the Forrest Avenue Consortium (that had become Nexus, Inc. by 1981) were the city’s crown jewels of the grassroots arts scene—the BCA expressly supported both organizations and, in the final years of CETA funding, funded positions at both. The Atlanta Art Workers Coalition Newspaper, whose CETA positions dwindled by 1979, noted that BCA funding decisions seemed “certain to divide further the already factionalized Atlanta art community.” Editors were especially dismayed that Forrest Avenue received twelve CETA positions when, in their opinion, it “increasingly resemble[d] a closed community” with an insular, exclusive network of artists and a shaky history of offering public access to the multi-use arts facility.

The art world experienced other divisions as well, including those around race. Though all women described the scene as somewhat fluid in terms of interracial collaboration and support, a few suggested that there still remained two art worlds: one white, one black. This is not surprising in a city where geographical, economic, and social segregation was entrenched; where there existed a vibrant black cultural world in southwest and west Atlanta that had been supporting a black arts scene for years; and where mainstream art spaces such as galleries and museums, as Paschall mentioned, especially favored the work of white artists. John Riddle, then director of NAC, suggested that the separation between black and white artists in the city had everything to do with racism in the larger culture: “It’s because racism is taught in America as part of the American way of life. It is a central thread in the fabric of America. It is taught and therefore practiced.” 17 The election of Maynard Jackson may have helped to shift boundaries. Reflecting on racial division in Atlanta arts in 1979, Jenelse Holloway (then chair of the Spelman art department) told interviewer Steve Seaberg that, since Jackson’s election, “The Black artist now feels he will be judged fairly. Black artists always felt before that no matter how good a Black artist might be, a White artist would always be placed above him.”

Observations and even complaints about racial division in the arts came from community members outside of the scene as well. The Forrest Avenue Consortium came under fire when the surrounding Forrest Avenue/Glen Iris Neighborhood Planning Unit (the city put the NPU system in place to encourage community participation in local government) fought city funding for the Consortium. According to the NPU, the Consortium, housed in an abandoned school, represented “unwanted white infiltration in a black neighborhood” (Forrest Avenue is now Ralph McGill Boulevard). The Consortium, it charged, had not opened itself up to the community as it has initially promised to do, and its board was, until the NPU spoke up, made up of white men. The City Commission heard the arguments from the NPU and ordered the two groups to meet and resolve outstanding tensions or city funds would indeed be withheld. Ultimately the Consortium agreed to allow the NPU more advisory input, as well as to offer the community free meeting space and designate classes specifically for the neighborhood. 18

The art world of the 1970s was deeply connected to the social tensions and political realities of that era. Young organizations had to contend, too, with the political nature of arts funding. In 1978, Congress restructured CETA, limiting the number of and wages for public service employment jobs. This change was a blow for the organizations that had relied on Title VI funding. 19 Only a few years later, CETA was effectively killed by the Reagan administration, which, as Atlanta Constitution reporter Douglas Lowenstein put it, “launched a broad assault on the major social welfare programs of the 1960s and 1970s,” including CETA. 20 An embattled NEA also lost funding in the 1980s, which, in turn, affected arts organizations in Atlanta and across the country. 21

Though the ATLas interviewees acknowledge division and the difficulties of losing public funding, they remembered most of all the creative buoyancy of the young artists who forged a new scene in Atlanta. This creative labor had lasting impact—the Forrest Avenue Consortium became the Nexus Center for Contemporary Art (and then the Atlanta Center for Contemporary Art); the Atlanta Art Workers Coalition Newspaper became Art Papers; and the Office of Cultural Affairs continues historic programs like the Jazz Festival. Not all of the institutions survived—NAC closed in 1990—but the activism of the 1970s did continue. Alice Lovelace, for example, went on to co-found the Arts Exchange in 1984, which, as she says, is “owned by the arts community, always run by the arts community, and has always had black leadership.” 15 All of the women interviewed for ATLas remain active as artists and/or arts administrators and all of them founded or helped to build important Atlanta art institutions (see the biographies below). When we asked them to address the legacy of the 1970s, they spoke to the activist spirit of that period as well as to the importance of acquiring space. As Lovelace argues:

Artists are homegrown. And they are grown because there is someplace to feed and nourish them. They don’t start off fully blown; they start off as infants and somebody’s got to let them stumble . . . And they have to have a place where they can do this. And that is the legacy we’ve held onto here.

Annette Cone-Skelton was born in LaGrange, Georgia, and studied at the Atlanta College of Art (1964–1968) and LaGrange College (1960–1962). She began exhibiting as a professional artist in 1968 and is represented with works in numerous museum, private, and corporate collections. She was the Managing Editor of Contemporary Art/Southeast (1977–1979) now Art Papers, Director of the Heath Gallery (1978–1987), and founded her own art consulting firm, Annette Cone-Skelton, Inc. (1987–2000). In 2000, she co-founded The Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia (MOCA GA) and remains the President/CEO/Founding Director today. She has served on numerous non-profit boards including Nexus Contemporary Art Center, Art Papers, Hambidge Center for the Arts and Sciences, Atlanta College of Art, and Metropolitan Atlanta Arts and Culture Coalition (MAACC). Currently she is on the Executive Board of the International Women’s Forum of Georgia and the Board of Visitors, Emory University.

Visual artist, curator, educator, and author Tina Maria Dunkley is director emeritus of the Clark Atlanta University Art Galleries in Atlanta, Georgia. In 2013, she received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Women’s Caucus for Art following her seminal publication, In the Eye of the Muses: Selections from the Clark Atlanta University Art Collection, commemorating the 70th anniversary of the University’s internationally revered permanent collection of American art. A Kellogg Fellowship in International Development offered Dunkley an opportunity to teach art in Recife, Brazil, under the auspices of the Georgia-Pernambuco Partners of the Americas. During the Cultural Olympiad of the 1996 Olympic Games, she produced the multidisciplinary program, African American Culture: An American Experience. Dunkley is currently creating work that conveys the discovery of her maternal lineage to the Merikin community of South Trinidad. Paternally, she is the granddaughter of Jamaican artist John Dunkley (1891–1947).

Julia A. Fenton was born in Tupelo, Mississippi. She graduated summa cum laude from Millsaps College with majors in philosophy and religion, and did graduate work at Pennsylvania State University in both philosophy and studio art, as well as undergraduate work at the Atlanta College of Art. She is founding editor of Art Papers magazine and Contemporary Art/Southeast magazine. She has served as Director of the Atlanta Art City Gallery at Chastain and City Hall East Gallery, Gallery Director and Curator of Nexus Contemporary Art Center (now Atlanta Contemporary Art Center), Executive Director of the Newport Oregon Art Center, Exhibitions Director for Spruill Center for the Arts, and Curator for Emory University School of Medicine. Her art has been exhibited nationally and internationally and reviewed in Art in America, Sculpture Magazine, ARTnews, ArtWeek, Art Papers, among other publications. In the 1990s, she helped revise the zoning ordinances for Toledo, Oregon, and was elected to Toledo’s City Council. She served on the Community Development Committee of the League of Oregon Cities, the Oregon Tri-County Council for the Aging, the Oregon Coast Zone Management Association (an advisory group to the governor on issues of ocean, port and commercial fishing management), and founding Board member of Crossroads Oregon (which developed and administered court mandated programs for domestic violence offenders). She has served on the Board of Art Papers and is currently Board member of The Hudgens Center for Art.

Currently President of the Georgia Alliance for Arts Education and formerly President of the Georgia Assembly of Community Arts Agencies Board of Directors, Laura C. Lieberman most recently served as the director of the Cultural Arts Council in Douglasville for more than a decade, leaving that position in 2014. A co-founder and former editor-in-chief of Art Papers (1979–1984), she has been involved with cultural community development in Atlanta and Georgia for more than thirty years. During the 1970s, she was an active member of the Atlanta Women’s Poetry Workshop and worked as a poet-in-residence for Georgia Council for the Arts and the Atlanta Women’s Art Collective where she curated Mappings, an exhibit of local feminist artists. While Development Director at the American Museum of Papermaking, she organized Speaking Volumes, a selection of artists’ books by southeastern educators. She co-curated Artists of Heath Gallery: 1965–1998, the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia’s first exhibition. Lieberman worked with Young Audiences of Atlanta as Development and then Managing Director. She served as Director of the Arts Clearinghouse for the City of Atlanta Bureau of Cultural Affairs for seven years. With a bachelor’s degree from Swarthmore College, she studied contemporary aesthetics at Pomona College with artist James Turrell in 1972 and attended the Harvard Business School’s Strategic Perspectives in Nonprofit Management program in 1999. Lieberman was a founding board member of the Metropolitan Public Art Coalition and of ArtsGeorgia, a statewide arts advocacy group.

Alice Lovelace is a cultural worker, poet, playwright, and arts administrator. She was a founding member and Executive Director for The Arts Exchange; Regional Director for the New Forms Regional Artist Initiated Grant program; Executive Director of Alternate ROOTS, Executive Director of the Atlanta Partnership for Arts in Learning, Inc.; and Writer-in-Residence and Director at the Neighborhood Arts Center. She worked with Toni Cade Bambara to organize the Southern Collective of African American Writers in the late 1970s, and was the coordinator for the 1980 Conference on Black South Literature and Art at Emory University. She has a master’s degree in conflict resolution from Antioch University. She has received numerous awards for lifetime of work in the community, including a 2002 Spirit of the Movement Award in recognition of her use of poetry to educate the public about issues of political and social justice. Since 1995, she has been co-editor of the “ARTS CHANGES” section of In Motion Magazine, an online journal dedicated to issues of democracy. In 2011 Alice and visual artist Lisa Tuttle collaborated on “Harriet Rising”, commissioned by the City of Atlanta Office of Cultural Affairs Public Art Program and Underground Atlanta, for its four-month long Elevate: Art Above Underground exhibit. The installation was named one of the fifty best public art projects in the nation by Americans for the Arts’ 2012 Public Art Network Year in Review.

Callahan McDonough has exhibited her paintings nationally as well as regionally. She has been an active member of the Atlanta Art Community for over forty years. She maintains a working art studio in the Old 4th Ward, and is now a semi-retired psychotherapist. Callahan was a founding board member for both the Atlanta Women’s Art Collective and The Atlanta Art Workers Coalition in the 1970s. Currently she is a board member for The Women’s Caucus for Art Georgia; she is also on the Art+Activism committee for WCAGA. She holds degrees from Clark Atlanta University, Master of Social Work, and Georgia State University, Bachelor of Visual Arts. She has been included in: Lucinda Bunnen’s Movers and Shakers in Georgia, an Artforum review by Glen Harper, Art Papers, and the first Governors Award: Georgia Women in the Visual Arts.

JoAnne Paschall is a book artist, printmaker, curator, librarian, and teacher who has been active in the Atlanta area for nearly forty years. She is best known for her work as the Director for Nexus Press, and in starting and building the artist book collection for the Atlanta College of Art. More recently she managed the Mayor’s Youth Program for the City of Atlanta.

A native of Quincy, Massachusetts, Louise E. Shaw served as Executive Director for Nexus Contemporary Art Center (now the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center) from 1983 to 1998. Prior to that she was Assistant Curator at the Atlanta Historical Society (now the Atlanta History Center) and Director of the Georgia State University Art Gallery. She currently serves as the Curator of the David J. Spencer CDC Museum at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Through the years, she has also worked independently as an arts management consultant and curator. She earned a BA In English and Studio Arts from Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, and a MFA in Museology from Syracuse University.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank all of the women who agreed to be interviewed and to share their documents and photographs. Thanks especially to Laura Lieberman who commented on and edited this article, and who shared her extensive archives from the period. Ben Goldman was our filmographer and without him we would not have been able to capture these stories; Jennifer Sutton provided organizational and transcription assistance: thanks to Ben and Jenn.