Citation: Palmer, Hannah. “Flash Flood: A Drowning in the Bottoms”. Atlanta Studies. July 2, 2025. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20250702

The following excerpt from my recent book, The Pool is Closed: Segregation, Summertime, and the Search for a Place to Swim, feels like the emotional heart of my book and it isn’t even about pools. It’s a story about the danger of suppressed water and systemic racism, and it was so stressful to write, I considered omitting it from the book. In comments from my peer review, Dr. Carolyn Finney wrote, “All the threads come alive in this chapter… I sat up when I read this and found myself leaning in hard.”

The following excerpt from my recent book, The Pool is Closed: Segregation, Summertime, and the Search for a Place to Swim, feels like the emotional heart of my book and it isn’t even about pools. It’s a story about the danger of suppressed water and systemic racism, and it was so stressful to write, I considered omitting it from the book. In comments from my peer review, Dr. Carolyn Finney wrote, “All the threads come alive in this chapter… I sat up when I read this and found myself leaning in hard.”

I heard about the drowning three times before it started to seem real.

The first time was at the Historic College Park Neighbors Association, held in a warm little chapel on a private school campus. I was there to talk about restoring the Flint River’s withered headwaters and how it could benefit residents on the Southside of Atlanta. The chapel was full of folks who owned the large, historic homes with the highest property values for miles, a bubble of wealth and whiteness in an otherwise Black community, lower-income working people, not wealthy ones.

Before I even made it through the lobby, a middle-aged white woman approached me and said, somewhat cheerfully, “You’re here to talk about the Flint River? I remember someone drowned in the Flint River.”

No surprise, I thought. The river is vast. I needed to deliver my slides to the podium.

“I can’t remember her name. She drowned right here in College Park and got washed into a drainpipe.”

I frowned, tried not to say something incredulous. The perennial trickle in those streams was only about three inches deep. How could someone drown in College Park? I took an interest in the tray of brownies.

“When was that?”

I had toured the headwaters streams in College Park—labeled the “West Fork” on old maps—and they looked like a series of narrow ditches carved along the backside of backyards and apartment buildings.

“Honey, do you remember when that lady drowned in the Flint River?” She called out to her husband, who was already seated in a pew.

This is not the news you want to hear before you step to a microphone and pitch the idea of uncovering lost waterways. Where was the meeting organizer to rescue me?

The husband did not recall. It was time to find our seats for the Pledge of Allegiance.

She had to be mistaken, but later that night, I searched the internet for anything about a drowning in the Flint River in College Park. This sounded like something I should know about, but without more details on the incident, it remained a mystery.

The second notice, months later, was also cryptic but harder to ignore. I was standing in a boardroom in front of a group of forty people, talking about urban runoff, when the slide on the screen behind me showed a triple box culvert bulging with stormwater the color of chocolate milk.

We stood there in the rain for a long time, transfixed by the churning water whipping branches and litter into the lightless pipe. Guy’s bright-red polo shirt the only color in my photos. There is no limit to how long he will watch water in motion.

Gesturing to this photo, I was interrupted by a voice in the audience, a moon-faced engineer in a necktie. He wagged his finger at the culvert.

“We lost one down there once,” he said, sounding like a funeral director.

“Ah, yes.” I rolled with it, a real serious look on my face. “Someone mentioned that at a neighborhood meeting.”

Next slide, please.

If I believed the story of the drowning, if I dared imagine it featured this particular dead-end culvert, I wouldn’t have taken my child to that site in the rain. Now it seemed both dangerous and haunted.

The meeting was the usual rush of PowerPoints, handshakes, and business cards. I left with leads to research and emails to return. As for the engineer’s dark comment, I filed it away as river lore. Ancient history.

The third time, I was admonished by the mayor at the kind of mahogany board meeting where there’s a gavel, an invocation, and nameplates at each seat. Again, I was there to talk about the forgotten Flint headwaters and their potential to revitalize the neighborhood.

My presentation went five minutes over, and I was sweating through my cardigan, but the questions and applause seemed sincere. Next up on the agenda was the unveiling of a big office park development where a neighborhood used to be.

I quietly exited to find a water fountain. The mayor of College Park was right behind me. He said, gruffly, “You know we had a drowning in the Flint River.”

He answered his phone then, striding toward the exit. He’d been the mayor for decades, a tall, white-haired fixture with the kind of drawl that belies the political intelligence and ferocity that has resulted in multiple reelections.

Again, no one was offering details, just the comment, like a warning. Be careful what you wish for.

***

I had to leave College Park, leave the watershed entirely, to finally learn her name.

I visited the Northwest Community Alliance, a small but often-quoted group of active Northside citizens, as a guest speaker one night.

They met in a small brick church in a leafy old neighborhood. No steeple, no stained glass, same modest dimensions of the 1950s houses on the block. Again, the passing of cookies and bottled water in lieu of communion. Announcements, followed by a couple speakers, a friendly exchange of questions and comments.

After my talk, an elegant Black woman in a bright dress waited to be the last to speak to me.

“I love what you are trying to do,” she said, “your daylighting the river and all, but you should also point out that it’s very dangerous. I had a cousin who drowned in the Flint River in College Park.”

I’m sure my face fell, jaw dropped. That sinking feeling must show on the outside somehow.

“Your cousin?”

“She drowned in a storm,” she nodded. “So, you have to be careful over there.”

I believe that’s all she wanted to say, just a polite footnote. She started to move away. Even though my composure was disintegrating, I could not let her go.

“I’ve been hearing about this,” I said. “When did it happen?”

“It was a long time ago. And I was living out of state at the time.” She paused. Eyes calculating behind her glasses. “Her sons were young back then. Now they are grown men.”

This was the moment the drowning became real for me. Became a person. I realized I had been reluctant to believe it was true.

“I remember her as a sweet kid. I was her babysitter one summer.”

I asked if we could talk more, stay in touch.

She handed me her business card. Beneath the Georgia Tech seal: Dr. Jacqueline Jones Royster, Dean, Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts.

“And what was your cousin’s name?” I asked cautiously.

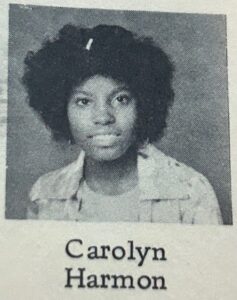

She spelled it as I scribbled on the back of her business card: Carolyn Harmon. The rumor, the warning, the mystery. It was her.

***

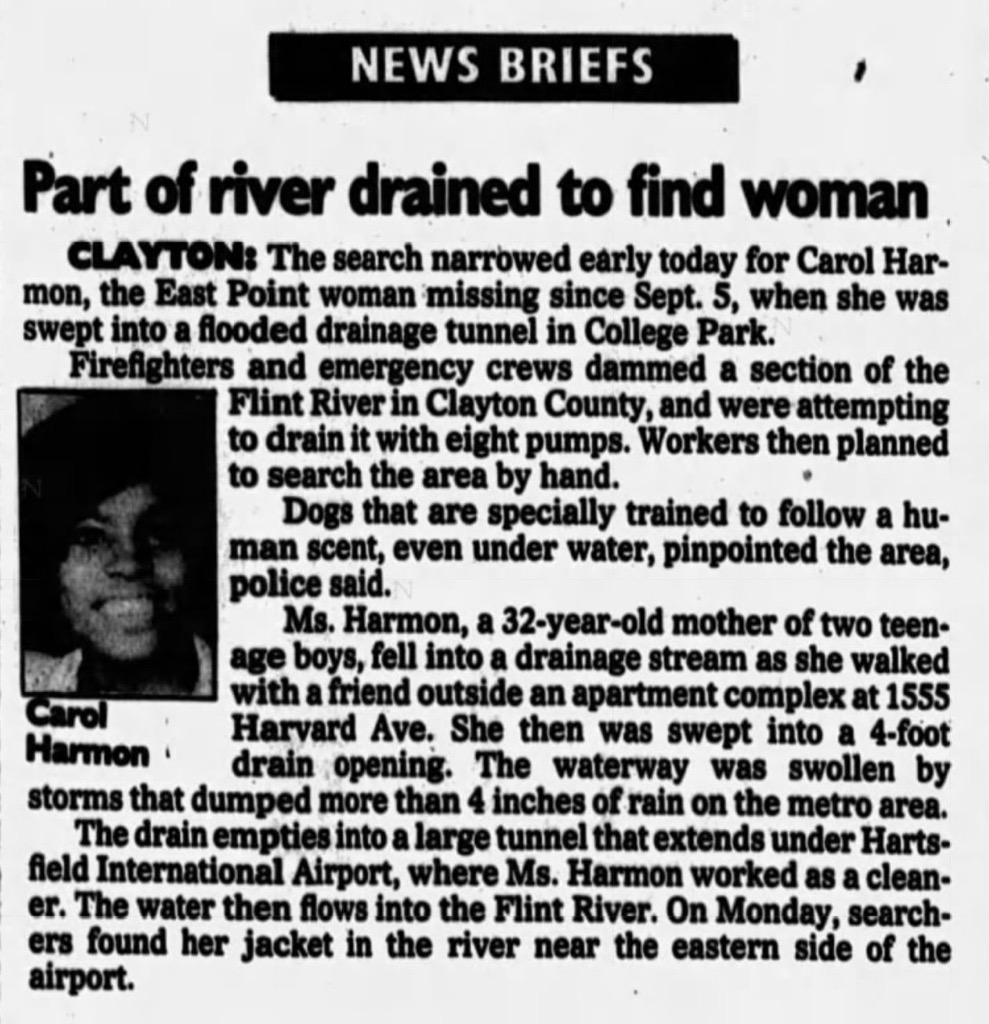

Her name unlocked the whole story. The next day, camped out in a busy coffee shop, I downloaded a handful of newspaper articles from Labor Day weekend 1992 covering the freak accident and the following rescue and recovery effort. I found myself wound into a ball, shivering and caffeinated, pulling my eyes occasionally away from my laptop to jealously observe the flow of normal life in the café.

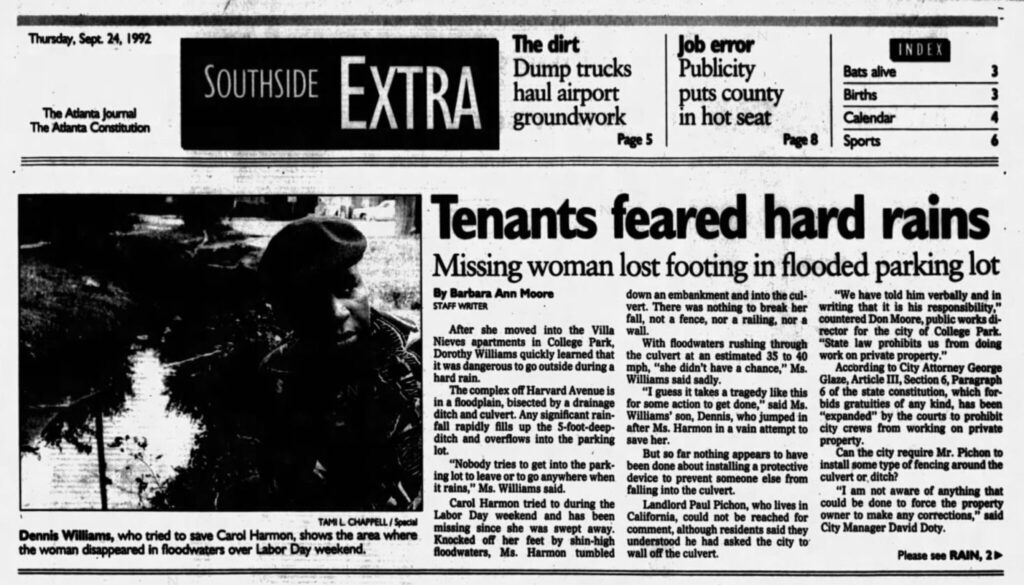

The Atlanta Constitution reported that late Friday night, September 4, Carol Harmon and her boyfriend started the holiday weekend at a friend’s place in College Park—the Villa Nieves Apartments on Harvard Avenue.1 When they arrived, it had been raining heavily all day, and the parking area was flooding. Apparently, there was a creek next to the parking lot that had overtopped the concrete footbridge connecting the parking lot to the apartments. That creek was the Flint River, but only an engineer would know that.

At one in the morning, Harmon decided to leave. She tried the back door, not realizing the path led into the floodwaters.

In one article, the water was waist-deep, in another, shin-high.2 Either way, it was high enough to obscure her path, dark enough to hide her proximity to the culvert, swift enough to make her lose her footing, and powerful enough to drag her under. Harmon was swept into a drainage pipe.

I didn’t let myself think about what happened next. Surely, I told myself, she lost consciousness before she had time to be afraid.

The accident didn’t make the news until Monday, Labor Day, in an article titled “College Park Flood Victim Still Missing” in the local section.3

“What bothers me most,” said Mattie Harmon, Carolyn’s mother, the voice of reason, “is a creek like that didn’t have a fence or wall around it.”4

The biographical details included in these articles read like cards stacked against her: a Black woman, a teen mom, a cleaning lady at the airport. There was no reference in the articles, as her mother points out, to her being more than “a cleaning lady.” She was an independent entrepreneur who had a cleaning business. Her thumbnail portrait showed traces of a smiling face, but the image was so dark and saturated, it became a black rectangle in the digital archives.

Search crews, including members from her church, spread out along the banks of the Flint River in Clayton County, on the other side of the airport. As police conceded that they may never find her, Mattie Harmon remained hopeful. She told a reporter, “I believe that she is holding on down in that place, somewhere.”5

That place. In future nightmares, I conjured the shock and struggle of her last moments, the crushing darkness and the tangle of branches that would become her grave. The media danced around the horror and violence of her death. The tragedy was part of a roundup of weather-related mishaps from the weekend, four inches of rain, widespread flooding, car accidents, residents evacuated to hotels.

A week later, volunteers found her jacket downstream, over seven miles away from where she disappeared.6 The search narrowed; trained dogs were brought in to recover a body. They searched in vain for another two weeks, but Harmon was never found.

Later Dr. Royster told me that her cousin has a grave but there’s no body in it.

A follow-up story, “Tenants Feared Hard Rains,” ran later that month in the Southside Extra section. Witnesses vented about recurrent flash flooding. Who was responsible for installing a protective railing or fence? The landlord believed it was the city’s job. The city argued that it couldn’t erect a fence on private property, nor could it force the owner to do anything.

On the same newspaper page, a column about “residents riled” over muddy runoff from the construction site of a ten thousand–seat megachurch ran next to a story about dump trucks hauling earth to build a new runway at the airport. Seeing this juxtaposition decades later, the relationship between these issues was glaring, but at the time, there was only a common anxiety running through these stories. Readers sensed the ground shifting beneath them.

Flooding always presents as local news, breaking news. Just an act of God, with no history or context. No one in the Southside Extra section was getting into technical stuff about increased impervious surfaces and stormwater volumes, connecting streamflow shifts to urban development. One piece called the site of the tragedy a “drainage system,” but before it was constrained to pipes and parking lot channels, it was a natural stream with a name. Did we think we could repress the Flint River forever?

The next article came from October 1994. “Ruling: Woman’s Death Her Own Fault: Judge Throws Out Family’s Lawsuit.” A Fulton superior court judge ruled that Harmon was, “by her conduct, the proximate cause of her own drowning” and refused to let the case go to trial.7

Reading this, my stomach turned. I tried and failed to imagine a fictional universe in which this headline might apply to a middle-class white mother violently flushed into an open sewer and never recovered. But we don’t treat rivers this way in white neighborhoods.

The Harmon family’s attorney vowed to appeal. “We think the judge was wrong. The conditions at that apartment complex were atrocious, the city of College Park and the apartment owners knew about those conditions and they ought to be held responsible.”8

A few months later, they would lose the appeal too.

***

I stewed over all of this and drafted a wordy and earnest email to Dr. Royster. I thanked her for introducing herself and telling me about her cousin. I told her I was piecing together what had happened.

“I would like to understand the conditions that led to this tragedy and what changes followed. I would like to be able to accurately tell Carol’s story as part of why we need to rethink these headwaters and their impact. Certainly, her story—and the larger story of environmental justice—is at the heart of any restoration work or new greenspace in the area.”

She responded promptly with a note of agreement, reminding me that her cousin’s name was Carolyn, not Carol.

I fumbled for my notes. Then apologized. The Atlanta Constitution had it wrong, which seemed like yet another indignity. I said there should be a memorial for Carolyn, so people would know her name.

A few minutes later, another note. She asked me to send links to the articles. She explained that at the time of the tragedy, she was living out of state and knew very little about what really happened. Dr. Royster and I traded a number of emails that afternoon. We agreed to keep researching and sharing.

What I didn’t say is that I was troubled by my own desire to ignore this story. It was sad and inconvenient to think about it. It didn’t fit into my pitch about river restoration. The news hardly covered it, the courts wouldn’t hear the case, and the city and landlord were too busy pointing fingers to acknowledge a family’s pain.

I stood in a long line of well-educated, well-meaning white people looking away from the truth. How could I even talk about saving the river without finding Carolyn and bringing her, finally, to light?

***

The next day, by chance, I had lunch with a friend who works as a paralegal. Over fancy salads, I blurted out what I had learned, that I wanted to write about it.

“Am I going to get sued?” I sputtered. “I mean, I’m not trying to reopen the case, or old wounds, but this is unbelievable.”

Later that afternoon, he emailed me a PDF fished out of the depths of one of those pricey legal research services: “Court of Appeals of Georgia. Harmon et al. v. City of College Park et al. Reconsideration Denied, July 26, 1995.”

The decision was only four pages long but offered a detailed analysis of the accident, most of it scrutinizing Harmon’s final footsteps. I found the focus not only wrong, filled with unfair assumptions, but cruel, even decades later.

The only voice of reason was P. J. McMurray, who wrote in his dissent:

I do not think that it can be said (as a matter of law) that Ms. Harmon was aware of just how precariously close the submerged drainage ditch was to the sidewalk she was traversing moments before her death. Most persuasively, however, is the absence of proof that Carolyn Harmon was aware of the powerful suction at the narrow drainpipes which ultimately dragged the victim underwater and jettisoned her body to some obscure location within the City’s sewer system. Under these circumstances, I cannot go along with the majority in saying that the evidence demands a finding that Carolyn Harmon had a full appreciation of the specific danger which caused her death.9

Exactly, I thought. Could I interview him? It took me a little while to figure out the judge’s name wasn’t P.J.; he was the presiding judge. Unfortunately, I gleaned this from his 2017 obituary, which read, “He took a special interest in slip-and-fall cases, standing firm in his belief of the jury system being one of the greatest systems ever devised by man. Valuing the right to trial by jury, Judge McMurray left a legacy to the people of Georgia by writing many dissents and believing that the public should have their day in court by a jury of peers.”10

Reading this remembrance, I felt a twinge of loss for the honorable Judge William Leroy McMurray Jr. and aspired to write a dissent of my own.

I reread these documents a few times before I understood that Harmon’s death was considered a “slip-and-fall” case. Like an accident caused by an over-waxed floor or a busted sidewalk. That explains the narrow focus on her final footsteps, her decision to go out the back door instead of the front, her failure to hold on to the fence as she waded into the floodwaters. On the boyfriend’s final words to her, how much alcohol he had consumed that night, his inability to rescue Carolyn from the whirlpool. All of the things she did or didn’t do to deserve death.

The argument was insane. Where was the analysis of the thing that actually stole her from us, the flash flood? How had a common parking lot transformed into an inescapable drain? Why was an apartment complex built on top of a creek anyway? And given all this, I shared her mother’s commonsense question—why was the culvert unsecured? How could Harmon ever imagine where the water came from or where it led? At one point, Dr. Royster mentioned that her cousin was a strong swimmer, but how would she know she was crossing a river?

I didn’t want to reconstruct Carolyn’s story as a true crime puzzle to be solved. Instead, I craved the historical context that didn’t make it into the grim news stories or the aborted court case, the bigger picture of urban development that had led to the flood.

I looked up the historic aerial images and topographical maps to see how the stormwater problem had been compounded over time on the block at the center of this story, 1555 Harvard Avenue. When the property owner sued College Park for damages, the city manager denied that they had done any work upstream that would “adversely affect” the property. Yet anyone could tell you the landscape had changed completely since the 1960s, when the apartments were built with a stream flowing through a neat little channel in the parking lot.

In the earliest aerial photo from 1938, College Park’s residential street grid unfolded from the central railroad tracks, the streets named for universities—Princeton, Columbia, Cambridge, Oxford. Our block on Harvard Ave. stands at the rural east edge of a booming town, between the College Park Cemetery and a patchwork of marbled fields where the Atlanta airport will soon stretch out its runways.

After World War II, College Park quadrupled in size. The crisp 1955 aerial photo was somehow much more detailed than any satellite image to come later. The rural edges of the city filled in with blocks studded with new houses. The Flint River’s West Fork cut a straight path from northwest to southeast, a wooly seam slicing through the city blocks. Low-lying areas remained undeveloped, allowing the creek to meander down to three small lakes clustered south of our block.

In 1960, some clever developers found a way to design small garden-style apartments into the previously undeveloped floodplain lots. At 1611 Harvard Avenue, a horseshoe-shaped complex was built practically on top of a stream, with decorative footbridges and floating staircases leading to the central courtyard. The stylish Villa Nieves Apartments at 1555 Harvard Avenue debuted in 1962, all thin white brick and Havana breeze-block. I counted eight of these creek-side apartment complexes still standing today, each containing a dozen units or less.

In 1968, the lakes disappeared. Where did they go? I might have cussed, toggling back and forth between the maps, before and after. They were drained to make way for interstate I-85, which amputated Harvard Avenue to the west of our block. That extra water would have to go somewhere. A decade later, I-85 was rerouted to make way for the new airport terminal, pulled northwestward even closer to our block. Another chunk of the neighborhood was wiped out; the noose tightened around 1555 Harvard Ave.

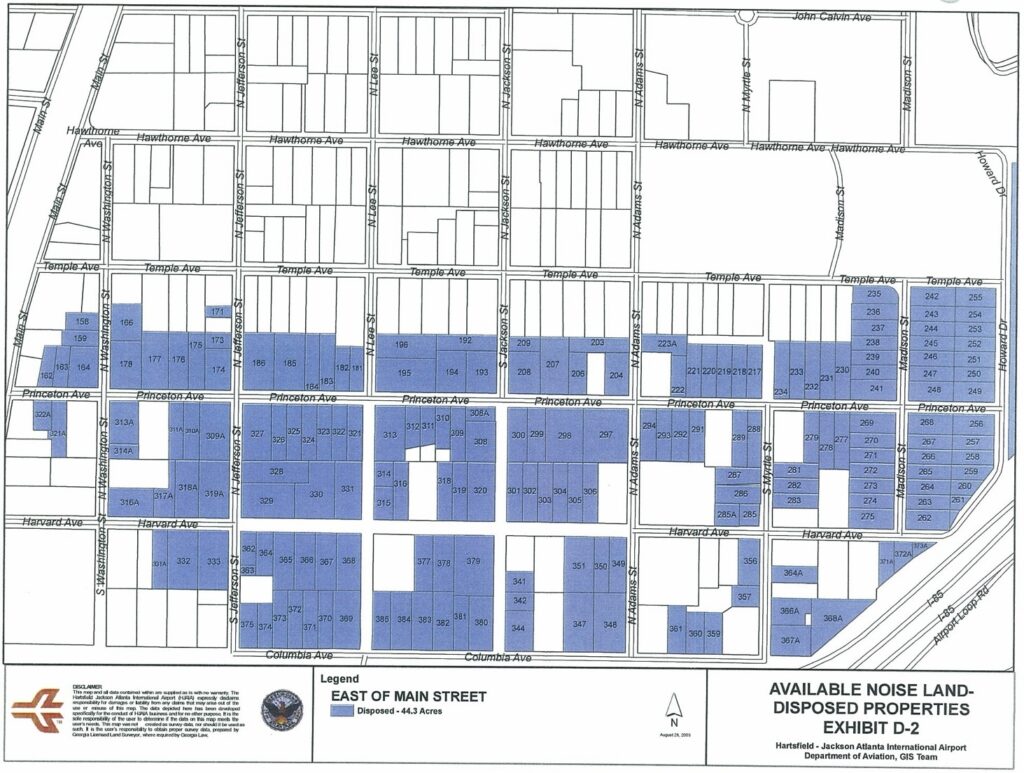

As the airport expanded in the 1970s, the Federal Aviation Administration began a program of residential buyouts in this area, relocating all the single-family houses that were impacted by airport noise. The apartment buildings were left standing, however, because this program didn’t cover multifamily units. The apartments where Carolyn drowned were left surrounded by empty lots, dead-end streets, and driveways to nowhere, a kind of postapocalyptic ghetto in the elbow of the freeway.

In less than four years, this corner of College Park was transformed from populated and forested blocks to vacant bottomland, designed for no one but populated, nonetheless. Who always settled in the Bottom, downhill from the mill, the factory, the city on a hill? The people who were less powerful, who have fewer financial resources—in this case, Black people who were ordinary laborers, factory workers, cleaning ladies, restaurant workers, delivery people.11

Add to the 1988 map a sprawling College Park MARTA train station and the headquarters campus for the FAA, both constructed upstream of our site, paving over twelve, then sixteen more, acres that once absorbed rainfall. A tangle of interstate ramps connecting to the airport terminal appeared, completing the transformation.

By 1995, the topographical map had fundamentally changed. The contour lines that followed the urban stream now drew a bullseye around 1555 Harvard Avenue. It was a dangerous place, an accident years in the making.

Eventually, after Carolyn’s drowning, the city of College Park engineered a solution for these flooding problems. In 2005, it rerouted the stream around the Villa Nieves, through a series of huge new retention areas that looked like grassy bowls carved out of a city block, surrounded by eight-foot-tall fences. Industrial-sized upgrades, forbidding and expensive. The parking lot channels were capped near the apartment building, erasing the scene of the crime.

Maybe the city finally made this investment because it took thirteen years to assemble the funds and the land to overhaul the storm sewer system. Maybe it waited until the lawsuits and media around the drowning faded away before starting in on the fixes that would prevent further tragedy. But if all of this had been done in the 1970s, around the time I-85 replaced the lakes, Carolyn wouldn’t have drowned, and countless residents wouldn’t have suffered through flooding.

Who is responsible for racism written into the landscape over a hundred years of development? I have implicated agencies at all levels of government here, from the Georgia Department of Transportation for plowing an interstate highway through a neighborhood and filling in a lake in the process, to the Atlanta airport for forcing a river underground. I can blame the FAA for funding the buyouts of houses but not the apartments, along with MARTA for underestimating the impacts of runoff from its new train stations and parking lots. I would blame the developers who engineered these apartments into floodplain lots, but their plans relied on 1960s hydrology, when this creek stayed in its tidy channels.

From my seat, they all look complicit, but only the lowest on the totem pole paid a price. The city of College Park lost a ten thousand–dollar judgment to the landlord in 1995. The landlord let the property go into foreclosure in 1996.12

Carolyn came last in the hierarchy.

In Harmon v. College Park, the judge points out that in her final moments, Carolyn Harmon failed to hold onto a chain-link fence on the left side of the walkway. This was supposed to be proof that “the victim failed to exercise ordinary care for her own safety.”13

Harmon’s family disagreed with this report. The family re-walked Carolyn’s pathway and found there was no fence or anything else to hold onto. This tragic death was not due to negligence of any kind on Carolyn’s part.

What was this fence, this evidence that sank the Harmons’ case before it ever began? Years after the drowning, I visited 1555 Harvard Avenue one breezy, blue morning after I dropped off the kids at school. I waited in the parking lot as a woman left an apartment, drove off to work, leaving the street empty. The old creek path left a grassy scar curving around the front doors of the apartments.

The little concrete footbridge was still there, though it crossed nothing more than a storm drain. My shoes squelched in the grass as I followed the indentation upstream from the parking lot to the engineered meadow of clover and cattails behind a tall security fence. The river, just a creek today, had been trained into right angles around the apartment building. I couldn’t see any water down there.

I took a few photos, waved at passing neighbors. Forgive us our trespasses, I thought. I must look suspicious back here.

Finally, I walked along the back of the building, ducking under kitchen windows, along the footpath that Carolyn followed. I was looking for what I couldn’t find in the maps and aerial photos.

To my left, up a berm and behind a security fence, lay the retention pond, the caged river, but this wasn’t there in 1992. Once upon a time, there were houses on that side of the block. Their backyards backed up to the Villa Nieves. If there had been a fence on the left to mark the edge of their property, all of that was demolished in the early 1990s. The fence wasn’t there to protect Carolyn from the stream. It was there to protect the homeowners from the apartment dwellers and the bad things that they thought happened on the other side of the fence.

From The Pool is Closed: Segregation, Summertime, and the Search for a Place to Swim by Hannah S. Palmer. Copyright © 2024 by Hannah S. Palmer. Used by permission of Louisiana State University Press.

Hannah Palmer is a writer and artist from the southside of Atlanta. Through essays, memoir, and public art projects, she explores the hidden histories and wildness that shape our lives in the urban landscape. Her award-winning memoir Flight Path: A Search for Roots beneath the World’s Busiest Airport (2017) was included on Atlanta Magazine’s list of “essential books that explain today’s Atlanta.” Palmer’s new book, The Pool Is Closed: Segregation, Summertime, and the Search for a Place to Swim was published by LSU Press in 2024.