Citation: Greer, Tammy. “Hip-Hop and Southern Impact.” Atlanta Studies. December 11, 2023. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20210202.

As part of the 50th anniversary of hip-hop, the 2023 music award celebrations have been nationwide from Milwaukee, Wisconsin to the residence of the US vice president. These celebrations have paid homage to the origin of a culture created by, centered around, and influenced by Black urban-centered communities nationally and worldwide. Hip-hop has influenced the music industry, fashion and design, language, and overall culture for the last 50+ years. We see the influence of African Americans and hip-hop through its artists in film and TV, through leaders of fashion design organizations, and even through commercials/ads. Overall, in recent years, there is no corner of the United States or global culture that has not been influenced by hip-hop.

While we celebrate the worldwide influence of African Americans through this genre of music, the challenges of hip-hop and its influence on communities have not been emphasized amid the accolades surrounding the 50th anniversary. To be clear, there have been many critiques of hip-hop from varying scholars such as Murray Foreman at Northwestern University and Jeffrey Ogbar at University of Connecticut. These critiques have focused on the impact on young white Americans, during the emergence of rap music into the mainstream in the 1980s and 1990s. Such critiques led to Congressional hearings, parental advisory labels, and bans on the sale of the music, as well as a First Amendment case regarding free speech filed by 2 Live Crew and their music.

In more recent years, scholars have discussed hip-hop’s impact on the communities that created the genre. One of the more recent publications providing a positive spin on hip-hop is Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South, in which scholar and critic Regina Bradley recalls music, videos, and life experiences surrounding her personal coming-of-age in relation to the Atlanta-based hip-hop group, Outkast (“Operating Under the Krooked American System Too Long”). Bradley uses Outkast, and other members of the Dungeon Family, as exemplars of the trend in which southern artists entered into the musical space that was then dominated by East Coast and West Coast rap and hip-hop artists. The Dungeon Family is a collective of hip-hop artists in Atlanta. These artists include CeeLo Green, Goodie Mob, Sleepy Brown, and Cool Breeze. During the 1980s and 1990s, these coastal artists were typically viewed as representing a harsher version of the Black experience, such as portraying gun violence and selling drugs, as compared to Southern hip-hop, which had a variety of musical undertones, specifically gospel, in its more up-tempo music. Specifically, Bradley focuses on Outkast’s fourth studio album, Stankonia. She uses Stankonia to simultaneously chronicle the growth of Outkast as a hip-hop group and her individual growth within and assimilation to southern life after moving to Georgia. While other musical artists existed before Outkast, Bradley argues that Outkast is an influential leader in bringing southern hip hop to the U.S. mainstream. They achieved this through the creation of the ‘dirty south’ sound, which includes elements from various music genres, as well as their ongoing experiments with sound and style, all while maintaining a nod to southern living.

Bradley begins with a thoughtful analysis: “The black American South seldom has room to expand past three major historical touchstones: the antebellum era, Jim Crow, and the modern civil rights movement” (4). Black southern history is thus reduced to 1) the antebellum era, which, especially for southern whites, tends to be romanticized along the lines of Gone with the Wind; 2) the Jim Crow era, which is identified with oppression, poverty, and discrimination against Blacks, and 3) the modern Civil Rights Movement, in which organizations and individuals took stances against government-sanctioned oppression and discrimination. Bradley’s contention that the United States’ southern region is more than these specific moments, particularly in Atlanta, Georgia, is the opening for a critical discussion about the rise of hip-hop in the region. While Bradley makes the critical claim that the United States’ southern region is more than the three historical touchstones, the music, lyrics, videos, and styles often exhibit elements of these eras. Yet Bradley’s observations are key to understanding why one can reject these specific timeframes as the totality of who southerners, specifically Black southerners, are as a group.

To characterize the southern region’s stories of Black life, Bradley cites various figures from Anna Julia Cooper and W. E. B. Du Bois to James Baldwin and Alice Walker, with Walker being a more modern view. In Bradley’s view, southern hip-hop is different from hip-hop of other regions because of language use (including southern slang), instrumentation and musical choices, and the narration of stories of living in former Confederate states. Bradley observes a specific interest in the “experiences of black southerners who came of age in the 1980s and 1990s and use hip-hop culture to buffer themselves from the historical narrative and expectations of civil rights movement era blacks and their predecessors” (6). These expectations, as Bradley notes, are for the descendants of Civil Rights Era Blacks to use education and the democratic process to aid in social, political, and economic achievement (11).

According to Chronicling Stankonia, these expectations were rejected by some of the younger post-Civil Rights Movement Black southerners, giving way to the hip-hop lyrics and style of the 1980s and 1990s, so that the United States’ southern region could be seen as more than a historical artifact associated with the antebellum South, the Ku Klux Klan, and Jim Crow laws. As Bradley chronicles Outkast’s music, Bradley identifies growth in the lyrics, video expressions, and underlying artistic messages. According to Bradley, Outkast challenges conventional thoughts of the region, noting “Southern hip-hop deromanticizes the mountaintop as prime real estate” of achievement by “the breaking of limitations about the South as a viable and vibrant space of creative reckoning with the past, present, and future” (20). The “mountaintop” refers to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s last speech at the Mason Temple in Memphis, Tennessee before King was assassinated. King noted “the mountaintop” is the place where Black people would achieve peace, civil rights, and equal treatment in the United States. This break with convention begins to critique how those outside the region view Blacks, and perhaps how Blacks in the region view themselves. Those outside the southern region perhaps viewed Black southerners as unserious, country, unartistic, uneducated, minstrel-adjacent, and not real hip-hop. On the other hand, southern Blacks viewed hip-hop as a reflection of southern living as slow/comfortable living, warmer weather, creative spaces, music genre blending, open spaces, and historical. Meaning, southern hip-hop, particularly Outkast, challenged the romanticized view of what it means to live in the South according to the three timeframes of the antebellum era, the Jim Crow period, and the modern Civil Rights Movement. This break also aligns with Bradley’s growth and view of the region through the eyes of her grandparents while living in middle Georgia.

While Bradley argues 1980s and 1990s hip-hop attempts to move beyond the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, one could argue that the very nature of Outkast’s “Git up, Git Out,” the entire ATLiens album, or even specifically “Liberation” are anthems of the very premise of the Civil Rights Movement by providing encouragement, hope, and empathy for the daily struggle Blacks in the South face. I would argue ATLiens expressed displeasure with and criticized the United States’ mainstream and even global conditions of poor people; therefore, ATLiens draws directly from the playbook of the Civil Rights Movement. Bradley’s claim that southern hip-hop expresses “images [of] what would happen if Black southerners moved past historical boundaries into the speculative space” (20) resonates with the aspirations of the Civil Rights Era mantra “we shall overcome.” Through Outkast’s lyrics and videos, there appears to be a nod to obtaining an education and civically participating, if only to acknowledge the need for political activism addressing the living conditions inside the Black community. This challenges Bradley’s claim that Outkast had an authentic rejection of education and participation in the democratic process. It appears that Outkast understood the importance of political activism; Outkast expressed their activism in the language and style of the day rather than the language of their parents and grandparents’ generation.

Further, the nostalgic images of clothing, lyrics, and events surrounding 1980s and 1990s hip-hop as well as the evolution of the genre by southern artists could be seen as the Black version of the white romanticization of the antebellum South. Southern hip-hop’s ejection of the conditions of how southern Blacks have been treated in the antebellum South compared to the current living conditions creates an illusion that there is a newfound social and economic prestige of southern Blacks. Yet, the totality of southern Blacks’ living conditions, even in the city of Atlanta (also known as “The Black Mecca” and “The City Too Busy to Hate”) has not progressed as we are led to believe. The demystified image of Atlanta in particular is confirmed by years of data that the children who are born in poverty in Atlanta have about a 4% chance of growing up to escape their parents’ poverty as adults (Saporta Report, 2022); further children in the traditional Atlanta public schools have less than a 40% literacy rate (even less for Black boys) per the National Assessment of Educational Progress , and per the Urban Institute the homeownership of Blacks in Atlanta is far less than that of whites. Overall, in the City of Atlanta, the Black population is 47.7% and white population is 39.1% DataUSA). Further, according to WelfareInfo.org, 18.5% (457,572 people) of the residents live in poverty. Of that 457,572, Blacks equate to 207,000 (or 28.5%) and whites 186,000 (7.5%).

Because of these data points and the notion of disparity in hip-hop’s storytelling, it is interesting how the cycle of such living appears to now be elevated to commercial success. As part of her work, Bradley appears to illustrate the cyclical nature of how hip-hop attempts to escape the current living conditions, while reliving those same living conditions in the music, videos, posters, costumes, and other forms of media that mimic real life. Recurring images and lyrics of Black experiences, especially violence and poverty, continue a cycle of poor Black exploitation by the very people who claim to want improved conditions of the overall Black community. The image suggested is that because some southern Blacks are making money from retelling these stories, Black exploitation does not exist or that southern Blacks have overcome systematic poverty and discrimination. Yet, some of the lyrics point to conditions similar to the very eras to which Bradley claims 1980s and 1990s hip-hop rejects.

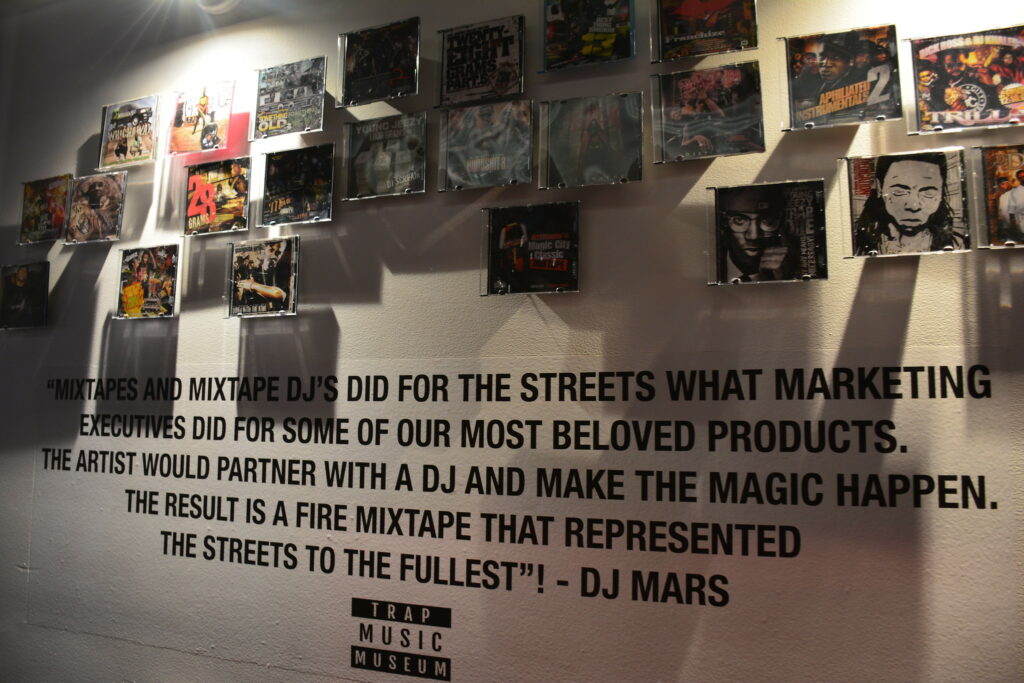

Bradley connects antebellum-era elements to southern hip-hop because southern living appears to be romanticized by the elevation of southern hip-hop. Bradley notes that the evolution of southern hip-hop created sub-segments of the regional music, specifically discussing trap music. Trap music has a different lyrical cadence and musical style from southern hip-hop. Trap music’s style has similar beats across the songs, in contrast to the variation in Outkast’s style, which incorporates elements from different musical genres such as rock-n-roll, blues, gospel, and rhythm and blues (R&B).

At its core, trap music creates a connected experience for its creators and listeners. Some are those living in “trap” conditions, individuals who can relate to being in confined conditions, or those who look voyeuristically on such conditions. Trap creates a feeling of being confined to cyclical poverty, crime-infested communities, and areas with low-achieving education systems where generations after generations experience the same realities. As the name notes, Trap Music tells the reality of being socioeconomically trapped in one’s conditions. Conditional familiarity creates an outlet for those in the “trap” to have a connection through experience–the affirmation that those in the community are not alone in the “struggle.” The “struggle” includes high poverty, high violent crime, over-policing, and the overall feeling of being forgotten or dismissed by local, state, and federal governments. This feeling of being forgotten then turns into apathy or nihilism. The apathy or nihilism becomes the culture of the community where the thought of being alive past the age of 25 seems unrealistic; the chance of being incarcerated is much more likely (Kubrin, 2005). In the trap, being a man is more in line with how stereotypically masculine you are. This stereotypical masculinity is more about being violent and involved in drug dealing (Balaji, 2009) than about taking care of one’s family or being a positive role model.

As trap music became more popular in “underground” music spaces, it then turned into a commercial hit. Part of the commercial hit of trap music is in the form of “keeping it real,” which is about the storytelling of the realities of these communities (Rose, 134, 2008). Therefore, trap becomes commercialized as the experiences of these poor southern Blacks are exploited for capitalistic gain (Maus and Donahue, 39, 2014). Thus, this is a return to emotional and psychological antebellum spaces where the exploitation of Black bodies and experiences is used for the monetary gain of others. In this case, the others are the storytellers, the Black men and women who make the music about the trap (or even who created a Trap Museum in Atlanta); the others are also the corporate entities that seem to find one style of music and exploit that music endlessly, or at least while sales continue to produce profit. Trap music appears to repeat the underlying music to allow music producers to create a collection of music cheaper while selling the records/albums for the same price. This means the profit margin is greater for recycled beats. While some will argue that the storytelling of being trapped is essential to illuminating the realities of the community, the trap appears to uplift the trap as “low frequency” (Maus and Donahue, 38, 2014) where those in the trap and those who have no idea of the complexities of Black life essentially equate it with being trapped.

As a form of music created by Black artists that incorporates fashion, visual art, and a way of existing, hip-hop is essentially a return to the same eras that Bradley claims southern hip-hop rejects. On one hand, we have the exploitation of the community for the gain of others, similar to the antebellum era. It can also be argued that being in the trap is a version of Jim Crow where mental, emotional, and physical silos were created for poor Blacks– reinforcing cycles of poverty and violence that provide content for capitalistic gain. Yet today, some of these artists are attempting to have a civil rights movement where musicians, producers, and other content owners are working towards finding equity and acceptance in mainstream (white) spaces to make a legacy for future generations. Therefore, even though Bradley contends artists reject the historical touchstones of antebellum, Jim Crow, and the modern Civil Rights Movement, one could very well argue that the cycle of hip-hop is another production of these three historical touchstones–just in a different form.

Cover Image Attribution: Cover of Regina Bradley’s book, Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South. Published by the University of North Carolina Press © 2021. Used with permission of the publisher, University of North Carolina Press.

Tammy Greer has a Bachelor’s degree in Criminal Justice and Master of Security Management (both from the University of Houston-Downtown), and Ph.D. in Political Science from Clark Atlanta University with focus areas in American Government, Urban Politics, Comparative Politics, and International Politics. As Clinical Assistant Professor and Director of the Bachelor of Interdisciplinary Studies in Social Entrepreneurship with GSU’s Department of Public Management and Policy, Dr. Greer’s interests include community and civic involvement with a focus on how policy and the lack of equitable public policy impact historically underserved communities. She is the author of the forthcoming book, Checks Without Change: Moving From Protest To Policy.