Citation: Renfro, Paul M. “Tough on Crime: Atlanta Monster and the Politics of ‘True Crime’ Podcasting.” Atlanta Studies. October 16, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20181016

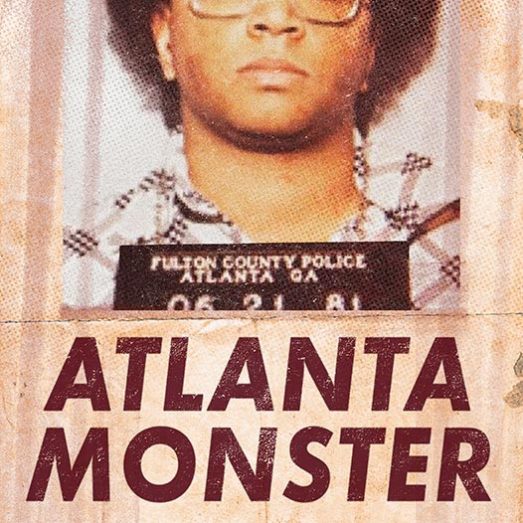

Nearly forty years ago, Atlanta – the South’s “black mecca” – came under siege. From 1979 to 1981, some twenty-nine economically disadvantaged African American youth were kidnapped and killed in the self-ordained “city too busy to hate.” While Atlanta boasted an African American mayor, public safety commissioner, and police chief at the time, its poor and working-class black communities took minimal comfort in their leadership. For many in Atlanta’s underserved communities of color, the city’s racially diverse political and economic establishment cared little about the wellbeing of its most vulnerable citizens; rather, it sought to preserve, at almost any cost, Atlanta’s reputation as a racially progressive, business-friendly southern metropolis. Critics claimed that this elite concern with optics and stability led investigators to identify Wayne Williams, a twenty-three-year-old African American man, as the “Atlanta monster” who had been terrorizing the city’s poor black neighborhoods, and especially its youngest residents. Williams was eventually convicted of two murders involving young adults – twenty-one-year-old Jimmy Ray Payne and twenty-seven-year-old Nathaniel Cater – but officials then implicated Williams in virtually all the other slayings, most of which featured victims under the age of sixteen. The task force formed to investigate the kidnappings and killings was disbanded shortly after Williams’ conviction. For those critical of the official investigation, its seemingly hasty resolution further demonstrated that elites had hoped, first and foremost, to shore up Atlanta’s racial and class order. By pinning the crimes on one African American man, officials could maintain the status quo, deny the explanatory power of race and class, and forestall any civil unrest within the city.

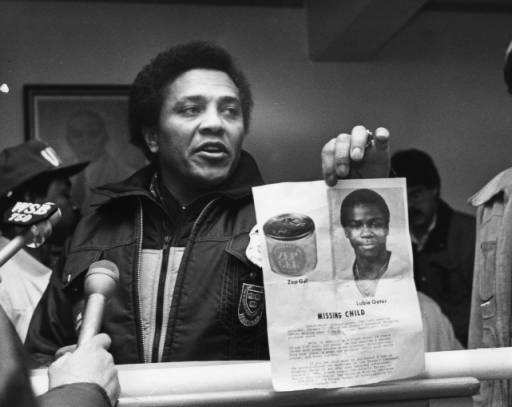

But perhaps most notably, the podcast Atlanta Monster – hosted by Payne Lindsey of Up and Vanished fame – quickly climbed the charts following its premiere earlier this year. It’s easy to understand why Atlanta Monster found an audience. The program emerged out of an established (and likely oversaturated) “true crime” podcast genre which has produced such hits as S-Town, In the Dark, and Serial. Moreover, the depth and complexity of the Atlanta cases invite the sort of sustained, textured treatment that a well-executed serialized podcast might provide. Atlanta Monster also seizes upon the limited public knowledge of the 1979–81 murders, especially among white Americans like Lindsey. Notably, at the outset of the podcast, Lindsey admits to only hearing of the cases recently, despite growing up in Georgia. Upon first blush, the podcast’s wide research base – extensive interviews with dozens of subjects, including Wayne Williams himself; archival television news footage; court records – suggests that Lindsey might actually make good on his promise to stage “the final debate over Wayne Williams and the Atlanta murders” (episode 6, “The Splash”). Yet in framing the murders as a “debate” and hewing to the “whodunit” conventions of the true crime genre, Lindsey belies the complexity of the subject matter and forecloses the possibility of a more nuanced, thoughtful, and analytical account. As Atlanta Monster meanders for ten episodes in a quixotic attempt to “close the door” on the kidnappings and murders, it masks the broader racial, class, and cultural significance of these tragedies.1 To be sure, the podcast delivers some compelling anecdotes and pithy soundbites from Williams, erstwhile detectives, and Atlanta residents who endured the terror of 1979–81. It presents evidence which seems to implicate Williams while also sowing reasonable doubt about his guilt. Atlanta Monster also makes a persuasive case against Klansman Charles T. Sanders, who has long been suspected of killing fourteen-year-old Lubie Geter. Yet very little, if any, of this information is revelatory. As early as 1986, a feature in Spin magazine named Sanders as Geter’s likely murderer, as did a 1991 article in the New York Times.2

Alas, Lindsey continues to heap it on, presumably in the hopes that some grand investigative insight will enable him to win “the final debate.”That insight never arrives, and by the final episode, Lindsey has apparently changed his tune. “[N]o matter how you slice it,” Lindsey explains near the end of the last episode,

This story is bigger than an investigation, bigger than a trial, and bigger than Wayne Williams. This case evokes deep emotions, even in people that weren’t directly affected by the killings, and from what I’ve seen, it’s inexorably tied to a feeling of social struggle. No matter who committed these crimes, the people of Atlanta – particularly the black community – didn’t feel safe or sufficiently supported. Through sensationalized media and heightened pressure, the children that were murdered almost seemed to become a secondary narrative to the story of Wayne Williams (episode 10, “Loose Ends”).

Lindsey should have applied this critique to his own podcast, which mostly ignores Atlanta’s young victims and “secondary victims” (in media scholar Carrie Rentschler’s formulation), while fixating on Williams and the slapdash sleuthing performed by him and the HowStuffWorks crew.3 Though Lindsey insists that he sought “to soak in as much as possible about this time period,” the historical context he establishes is woefully thin. For a nine-hour program focused almost exclusively on late 1970s and early 1980s Atlanta, the podcast says shockingly little about the city and its people in that historical moment. Lindsey does well to interview Calinda Lee, vice president of historical interpretation and community partnerships at the Atlanta History Center, who astutely emphasizes the “racial bifurcation” evinced within the 1979–81 murders and gestures toward the class dynamics at play therein (episode 1, “Boogeyman”).

Yet Lindsey fails to adequately build on Lee’s insights, and thus the anxieties shaping black responses to the murders receive short shrift. President Ronald Reagan’s name is hardly mentioned (if at all), thereby precluding any discussion of Reagan’s racist appeals to “law and order” and “states’ rights.”4 The Atlanta murder saga unfolded less than ten years after revelations of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment broke and amidst a resurgent white nationalist movement emboldened by Reaganism and the 1978 publication of The Turner Diaries. Through widely circulated rumors blaming the Atlanta slayings on the Klan, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, many African Americans thus located the killings within a larger (possibly state-sanctioned) backlash to the black freedom movement. Unfortunately, Lindsey refuses to do the same. Indeed, he overlooks the civil rights movement altogether, even though many of the rhetorical flourishes and organizational strategies deployed in response to the murders – by the Committee to Stop Children’s Murders (STOP), the Techwood Homes “Bat Patrol,” and other parties – drew on the traditions of the “classical” freedom struggle.5

Oddly enough, Atlanta Monster reveals more through its shortcomings than it does through its successes. In their failure to “close the door” on the Atlanta murders, Lindsey and his podcasting team demonstrate not only the folly of their project and the inadequacy of their investigative methods – but also the limitations and perverse priorities of the “true crime” genre. By privileging a “Manhunt” – the title of Atlanta Monster’s second episode – over the structures and systems which facilitated the Atlanta tragedies in the first place – economic dispossession, white flight, ghettoization, and the devaluation of black and brown bodies – Lindsey and his associates reify the very inequalities they choose to ignore. Produced in our contemporary moment of naked white nationalism – as young people of color in Atlanta and nationwide continue to be disproportionately cut down through mass incarceration, gun violence, and otherwise – Atlanta Monster nevertheless portrays the Atlanta cases as aberrant, a peculiar puzzle to be solved by do-gooding gumshoes. Yet the intersecting causes of the Atlanta slayings, racialized policing and punishment, the lynching of Emmett Till, the caging of Latinx children at the US–Mexico border, and the murders that spawned #BlackLivesMatter are no mystery.

Or as civil rights activist Charles King noted at the height of the Atlanta saga,

We handle our children in this society without the proper kind of undergirding – economically or educational(ly) – that would give them a chance in life. This, my friend, is murder – before they die. We slay them before they have a chance. And if you really want to know who the real killers are – it’s not just the one or two people that we’re searching for. The real killers are the whites who condone it; black politicians who don’t give a damn anymore about what happens to black people because they’re fighting each other to gain office. And even if they wanted to do something about it, and even if they are still sensitive to the problems of black people, they are powerless to change the situations that white institutions initially set into motion and created ghetto conditions (sic). It’s almost, like, cast in concrete. So if you really want to know who the real killers are … the real killers are us. 6