Citation: Allums, Coleman. “Book Review: The Political Life of Urban Streetscapes: Naming, Politics, and Place.” Atlanta Studies. January 30, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20180130

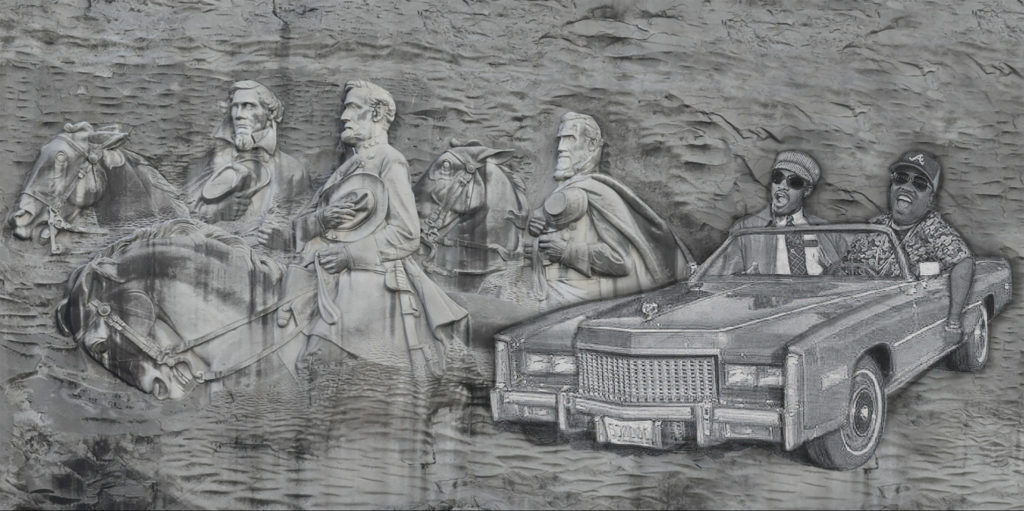

I distinctly remember, for instance, encountering a digital rendering of Stone Mountain’s (in)famous homage to the Confederacy, reimagined instead as a tribute to the South’s true heroes, OutKast1 (the notion of Stank Mountain, as the refashioned monument would be called, is one I fully endorse.) What these and related conversations lay bare – and what black activists, geographers, and others have been pointing to long before these conversations – is the essential sociopolitical construction and contestation of our landscape. The space around us is produced and reproduced through political and social practices and is always already riven with contradictions and marked by sediments and signs. How are we to make sense of all that the spaces and places around us contain, signal, and repress? By what means might we struggle for justice in the urban streetscape?

The Political Life of Urban Streetscapes, a recent volume edited by cultural geographers Reuben Rose-Redwood, Derek Alderman, and Maoz Azaryahu, offers a response to the complexities of deciphering, contesting, and making use of landscape through the study of critical urban toponymy, or, more simply, the critical study of names and naming in urban space. In particular, the essays collected in this text highlight the politics of the everyday, using the hermeneutic of street-naming to ask incisive questions about technologies of power, cultural memory and imagination, textual landscapes, boundary-making, and the conditions of possibility for political struggle over the material and cultural spaces of the city. In our current moment, these questions matter a great deal, and their answers may lay foundations for emancipatory political and cultural projects to come. For, as the editors remind us, “the urban streetscape is a space where different visions of the past collide in the present and competing spatial imaginaries are juxtaposed from one street corner to the next” (1).

Perhaps most compelling – and truly critical – in this volume are the co-authored introductory and concluding sections, which highlight the contradictions between the politically charged reality and the everyday experience of urban places. In these pages, the editors insist on an understanding of the meaning of urban places as not immediately accessible to surface-level observation, but as sedimented, ideological, and complex. They argue convincingly that the naming of places is itself an “act of world-making” and that the systematic structure imposed upon urban places “is necessarily a contingent spatio-temporal order, which is always open to the possibility of contestation and transformation” (19). Moreover, they critique prior scholarship on place-naming – which treated names as mere cultural indicators or historical curiosities – as banal, descriptive, and atheoretical. In its place they promise a new approach more attuned to power, politics, and the possibilities of urban space. On that promise, this collection largely delivers. As a volume claiming to highlight the critical turn in toponymic engagements with urban space, Political Life offers compelling articulations of the mechanisms by which we might come to sift through urban places and place-names in search of meaning as well as a variety of rich historical engagements with particular urban spaces and the streets that contain and are contained by them. From Berlin to South Africa to New York City, the contributing authors turn their critical gaze onto the production of urban places, challenging conventional notions of time and space, and highlighting the unavoidably political character of memorializations, names, and boundaries.

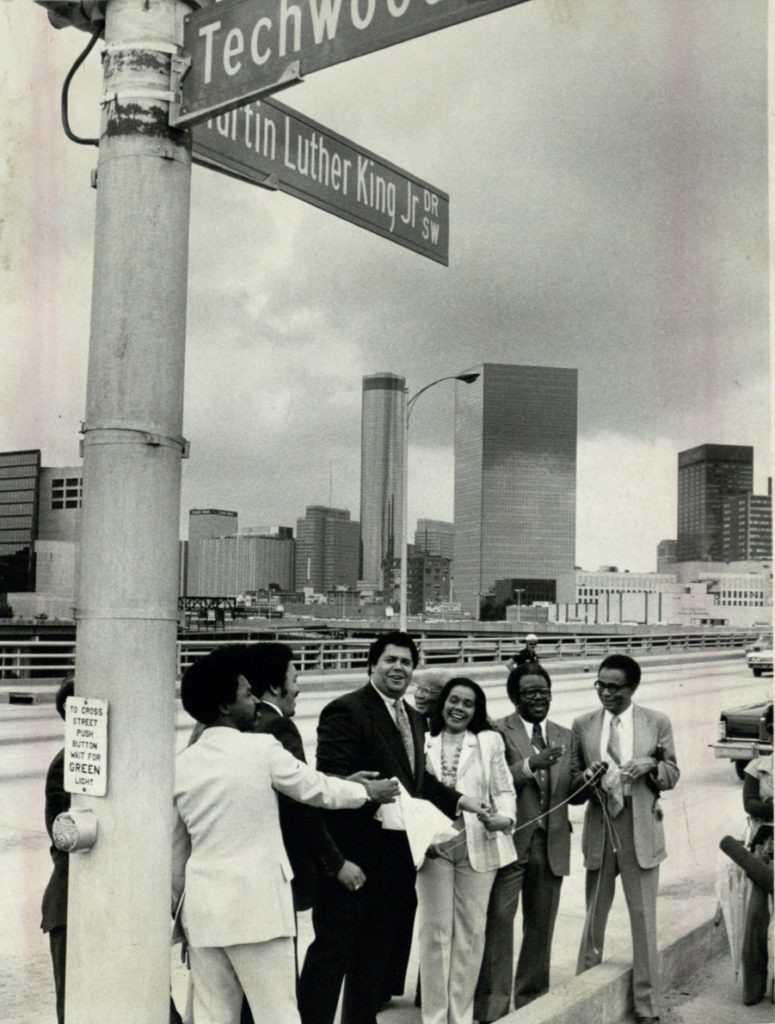

In one essay, Danielle Drozdzewski analyzes the ways in which memory and history, as reified through street naming, have performed techno- and geopolitical functions, establishing sovereignty and authority of sequential governments (Nazi, Soviet, Polish) in Polish urban space. In another essay, Emilia Palonen draws on socialist rhetorical theory (in particular, that of Ernesto Laclau) to argue that the revision of street names by local authorities in Budapest constitutes a “changing of the guard” that produces new – and uneven, unsettled – sets of meaning as the fluid city-text is read and engaged. Elsewhere, Alderman and Josh Inwood provide an account of oppositional place-naming, unpacking the promise and pitfalls of naming streets in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr., and analyzing how this highly contested and at times contradictory practice operates as both a spatial tool for black communities seeking to claim a right to the city as well as a barometer for ostensibly colorblind racial politics in the United States. These and other contributions to this volume offer timely approaches for thinking about Atlanta, particularly amidst ongoing discussions over the renaming of streets such as Confederate Avenue, and help to lay bare the contradictions and political possibilities of Atlanta’s city-text.

However, over the course of the volume one occasionally detects strains of the older, descriptive approach the editors are so keen to toss away, as some contributors seem at times more invested in (or perhaps, by the power of epistemic inertia, impelled towards) cataloguing than clear, committed theorizing. Perhaps it is an unfair criticism, or a marker of the singular, imaginative vision of the editors, but I cannot help but feel that the political, theoretical light dims ever so slightly in the empirical, textual contributions between the powerful introduction and conclusion. Nonetheless, this volume surely represents an important tool for thinking through the urban politics of the everyday. It foregrounds the lived spaces of the city as sites where power cannot only be made visible, but also contested, and where different meanings might be made. We in Atlanta, following this lead, must ask difficult – but eminently necessary – questions about the places we inhabit and traverse from day to day. What histories are brought forward or pushed away in our streets and our public spaces? How do our urban places – and the processes that continue to remake them – allow or repress political imagination towards justice?