Citation: Yow, Ruth and Sarah O’Brien. “Voices Rising: Translating Methods to Teach Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. November 16, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20171116

Well what Cabbagetown was . . . I guess, a community in Atlanta – or a neighborhood – of all these people who worked in – it was a mill village. So they were poor and then the mill was gone, but they were always very independent of the rest of the city. And so then they were very poor, and naturally that made for drugs and hustlers and wonderful things that we like – the good things in life . . . 1”

As emblematic of its region? As defined through and by its cultural producers and products? As embodied by its monuments and memorials? Like so many scholar-teachers before us, we find questions about how we – as teachers and students – know and communicate knowledge about cities to be vital to how we inhabit them, interact with fellow denizens, and potentially enact change in our shared spaces. As scholars who work on cities, their voices, their histories, and their futures, we set out to co-teach an interdisciplinary first-year composition course about Atlanta, a city whose “spiritual strivings,” in the words of erstwhile resident W. E. B. Du Bois, alternately inspire and exasperate us.2

Benjamin Smoke’s meditation on his neighborhood’s history and identity – as dark and sardonic as it is appreciative and fond – reminds us that the impossibility of finding coherence or singularity in the voices of a city is exactly the joy and challenge of teaching it. Over the course of planning and teaching our class, our approach to understanding and teaching city identity emerged as appropriately Atlantan: we viewed and attempted to frame this city to our students as confused and confusing; as a sparkling corporate fiction; and as a neglected historical artifact. Atlanta is a place whose long “adolescence” (to paraphrase anthropologist Charles Rutheiser) spent navigating both its “Black Mecca” and white supremacist pasts invites creative methodological exploration and innovative course building.3

To teach a city with a particularly unruly identity, we sensed the importance of elaborating a solid framework for the course. “Documenting Atlanta” spanned the city’s environs and history in order to explore how Atlanta has been represented and narrated in three cultural moments: the social movements of the mid-twentieth century; the 1996 Olympics; and Atlanta’s contemporary urban “renaissance,” embodied by the Atlanta BeltLine. Each of these units aligned with a methodological lens and attendant project: oral history and the production of an oral history-based podcast; documentary film and the authoring of an analytical essay; and built environment studies and the design and proposal of an on-campus memorial or monument. In this article, we enter an already energetic scholarly conversation about researching the built environment and teaching “place” by investigating how our methodological approaches to teaching Atlanta – those of an oral historian and a documentary film scholar – draw on distinct yet complementary ideas about narrative, voice, evidence, and representation. The very different work that methods do in the classroom and “in the field” – and the productive friction of that difference – is exemplified in the planning of the course, the selection of materials, the crafting of assignments, and the engagement and responses of the students. We thus begin by explaining our course’s syllabus and guiding structure, as well as our primary assignments, before turning to a more extended consideration of the methodological questions of knowing and documenting urban spaces.

Our focus on methods attests to their centrality in our pedagogy, both our own individual classroom strategies and the shared approaches we developed (some with foresight, some more improvisationally) to teaching Atlanta. As researchers, we use methods to spark questions and to complicate existing narratives. Contrastingly, in the classroom, our first-year students trust documentary sources to provide information, answer questions, and craft logical trajectories. We began from the belief that it is important to teach methods as a way to deconstruct what we and they encounter as “Atlanta.” This conviction was challenged, but ultimately strengthened, by the experience of attempting to creatively translate our research methods into lenses our students could apply, and make their own, in critical exploration of Atlanta.

We view documents as kinds of “voices” and documenting as a power-laden process of tracing voices. While this shared understanding made a thematic organization/emphasis tempting – for example creating units focusing on the marginalized voices of filmmakers, poets, entrepreneurs, and activists who shaped Atlanta’s identity – we wanted to offer our students a “center” through which to teach margins, and this made a chronological approach more logical. Ultimately, we chose the three sequential “cultural historical” moments referenced above: the Civil Rights Movement, the 1996 Olympic Games, and Atlanta’s current era of urban redevelopment.

We in fact started with this last moment, beginning the course with a chapter from Ryan Gravel’s Where We Want to Live: Reclaiming Infrastructure for a New Generation of Cities. Gravel – the progenitor of the BeltLine, a metro-Atlanta native, and a Georgia Tech grad – sums up his initial reaction to moving into the Georgia Tech dorms in the 1990s with the admission: “I had no idea where I was.” 4 A site that exemplifies the displacement of disadvantaged communities by corporate interests, those very dorms had just become our students’ temporary domiciles, and we knew this sentiment would resonate with them – both those who, like Gravel, grew up in Atlanta’s suburbs, and those who had moved here from other towns, states, and countries just days prior.

By presenting this chapter as something of a frame for the course (we would return to read several more chapters at the end of the semester), we commenced with the implicit promise that we would deliver students from their initial outsider ignorance to well-informed citizenship. Our choice of three distinct cultural moments also reflected a wish to apply political, economic, and environmental lenses to our study of Atlanta and our analysis of knowledge production about it. In this ambitious endeavor, we had the support of Georgia Tech’s Office of Serve-Learn-Sustain, which facilitated our teaching through a sustainability-themed Course Design Studio and numerous other pedagogical ventures. We hoped that students would be able to, through the course’s materials and assignments, engage the concept of sustainable cities – and the idea that sustainability has political, economic, and environmental dimensions. The “sustainable city” has gained traction with a diverse array of constituents: from scholars and urban planners to community organizers to corporate boards.5

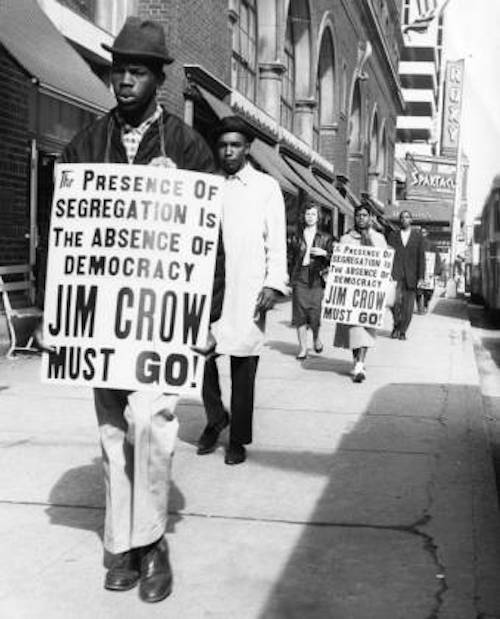

Our students had already been exposed to common notions of sustainability – if only by recycling and Earth Day programs at their high schools – so we aimed to propose a multidimensional (and multidisciplinary) perspective on sustainability that was attentive to its social manifestations: the modes of equity-oriented sustainability defined and modeled through the grassroots organizing and political activism of the Civil Rights Movement; the ways that the big business of the Olympic Games – what Rutheiser calls the profit-driven “imagineering” of a new city – fundamentally remade Atlanta’s downtown around the green of dollar signs, not expanded tree canopy or clean energy efforts; and, finally, the accessibility and long-term impact of sustainable city initiatives like the BeltLine.6 These investigations, complemented by a series of community service opportunities, were intended to involve students in sustained reflection on the city they live in, and the way that particular cultural historical moments – and representations of those moments – exert continuing influence on the lives of Atlantans across a diverse spectrum.

A syllabus makes arguments, and we understood ourselves to be making implicit arguments about the importance of the Civil Rights Movement, the Olympic Games, and contemporary redevelopment projects by enshrining them as “units.” Despite our wish to avoid any suggested equivalency between the Civil Rights Movement and the Olympics, we saw these moments as opportunities for intervention vis-à-vis the methods of our disciplines and trainings. We also assumed a degree of familiarity (at least for American students) with all three of these moments, and in some ways let that familiarity stand for broad content knowledge: we imagined that students would have visited Centennial Park in outings with their parents, made a stop at the Martin Luther King Historic Site, and taken an afternoon stroll on the BeltLine.

Students’ passing familiarity with these moments and their associated places and leaders did indeed provide a foundation by which they could begin to identify how master narratives and consensus memories are reinforced in the memorial landscape of the city around them. We were willing to risk re-enshrining the Olympics (and the city’s paeans to diversity and internationality) in order to offer Centennial Park as an intellectual playground, such that students could experience “built environment studies” as they explored “how historical discourses are represented and given authority via the landscape.”7 We intended that our syllabus, and its three foci, would make an argument not for the unique importance of the three moments, but for how those moments compose a narrative about Atlanta that demands the interruptions and disruptions of other voices, richly accessible through the local physical landscape and through the oral historical and documentary film record.

Planning the course readings and lectures further illustrated the productive tensions and challenges inherent in centering methods in a classroom of students with very little content background – especially as we strove to shape our units around questions of hegemony and history, voice and representation, and margins and center. Many possibilities emerged in terms of choosing specific sites of analysis that could at once provide key context and raise compelling methodological questions. The Civil War was an obvious – if much taught– option: what cultural documents about Atlanta don’t have, as either their latent or visible genealogy, slavery, war, and the transformation of a once-backwater railroad town into the South’s major metropolis? Students, whether from Newnan or Nigeria, would feel themselves on familiar terrain in a Civil War unit, and the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the conceptualizing – and selling – of the “New South” are crucial touchstones for understanding Atlanta in its historical context.8

So we decided on newspaper man and deft political operator Henry Grady to give voice to the New South through a brief cameo in our introductory unit, “Atlanta History 101.” Through that “101” we established some historical framework for our students, and introduced the themes that would animate our units and drive our course goals.

Some ten weeks later, the retrieval and well-intentioned rehabilitation of Grady by a student group whose final-project proposal celebrated his vision for the New South underlined the dangers in “conceding” and placing Grady at the “center.” Du Bois, or even better, Atlanta’s black women laborers richly documented by historian Tera Hunter, could have served as the voices of the postbellum South.9 Yet students, we theorized, needed Grady in order to appreciate how the New South he described – racially harmonious, industrially productive, and a crucial partner to the North in national economic prosperity – influenced the next century and more of thinking about Atlanta’s destiny. In our course trajectory, oral history from African Americans provided a counterpoint to Grady’s Atlanta. We imagined that like a photographic negative, narratives from the margins would delineate the center and not re-inscribe it, but if it is through the margins that students are asked to comprehend the power relations that constitute the master narratives at the center, then our selection of voices needed to reflect that guiding injunction.

Asking students to conjure a clear picture out of a negative – one they could analyze, critique, and set alongside a host of other equally slippery documents – was, as we found, quite a lot to demand.

To more deeply explore the relationship between power relations, the margins, and the production of history and to provide students with a suitable theoretical framework as they approached their first major project, we chose Italian historian Alessandro Portelli’s 1981 essay, “The Peculiarities of Oral History.” In it, he poses questions about the “different credibility” oral histories possess and persuasively argues that “oral history is not the point where the working class speaks for itself.”10 Portelli’s text lent students a critical lens on the interviews from Living Atlanta and from the video oral history project Unspoken Past, which documents the experiences of (mostly white) gay men who came out in Atlanta in 1970s and 1980s. To those, we added selections from the Georgia Women’s Movement Oral History.

We supplied students with questions to urge them to think about how the agendas of interviewers and the race, class, and gender power dynamics that inhere in every interview affect the archive that is produced. In turn, each of the archives we used has limitations that raise important questions for research and for classroom teaching: Living Atlanta has an accompanying volume which contextualizes the interviews and integrates them into a narrative about the period (1914–48) they address, but the digital archive is almost overwhelming in its sheer volume (it is also unadorned – no accompanying images or vivid excerpted quotes invite the listener to explore the vast collection). Contrastingly, the Georgia Women’s Movement project features only excerpts and short clips, no full interviews or transcripts are available online. Such clips have a double edge – their brevity is alluring to time-strapped undergraduates, but the lack of full interviews, particularly the questions that produced the dialogue, obscure important registers of “performance” and “positionality,” in the words of pioneer oral historian and feminist Sherna Gluck, that are relevant to the production of that historical knowledge. Exposure to those interviews and other digital projects such as ATLMaps and the Peoplestown Project nuanced our students’ understanding of Atlanta before, during, and after the Civil Rights Movement, but it also introduced interpretative snarls that key terms like “hegemony” could not untangle.

Selecting documentary films for the course was similarly fraught and ultimately fruitful. Significant strains of documentary film – particularly “participatory” traditions of ethnographic filmmaking and cinéma vérité – “give voice” to suppressed stories of marginalized individuals or groups and, in doing so, demand attention to the medium-specific ways (e.g. editing, voiceover narration) in which power relations are alternately occluded and (seemingly) laid bare. More broadly, and thanks largely to the field-defining work of documentary film theorist Bill Nichols, whose Introduction to Documentary we assigned to our students as a “framing text,” the first line of discussion and analysis of any documentary frequently lands on “voice,” or “the specific way [a documentary] express[es] its way of seeing the world.”11 For Nichols, documentary voice is most closely apprehended through examination of the classical rhetorical departments of invention, arrangement, style, delivery, and memory. Voice includes yet lies in excess of style (the particularities of mise en scène, cinematography, editing, and sound associated with fictional films) because it bears “an added sense of ethical and political accountability” as it “give[s] concrete embodiment to a filmmaker’s engagement with the world.”12 Our methodologically aligned interests in voice surfaced organically in our sequential units on oral history and documentary film, and in future versions of the course we would do well to strengthen it as a throughline accessible to our students.

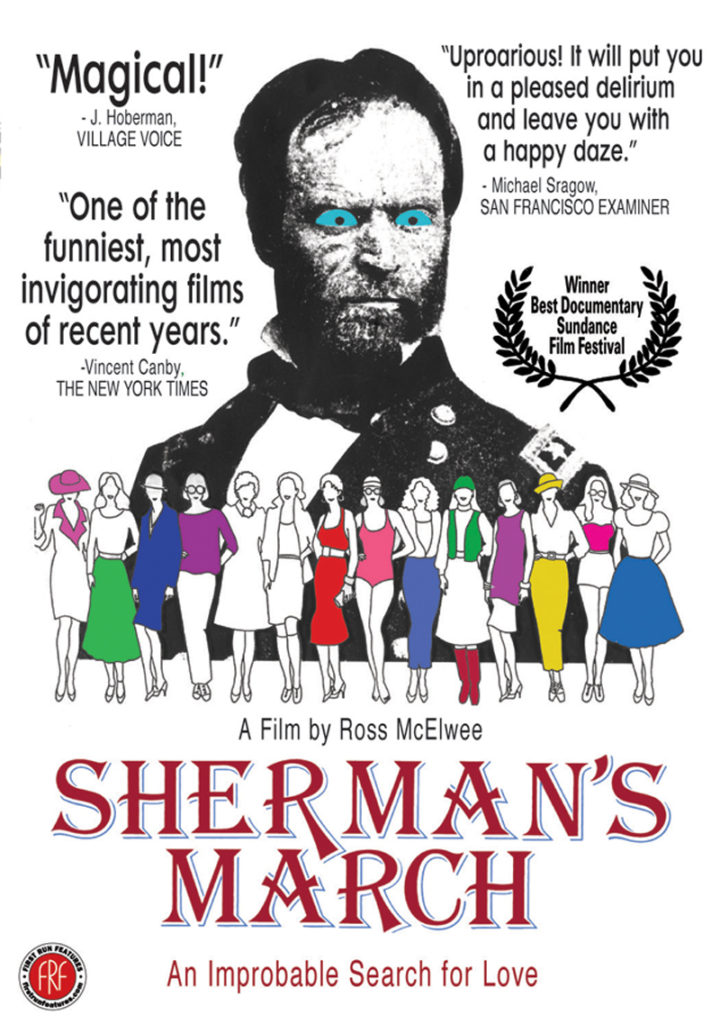

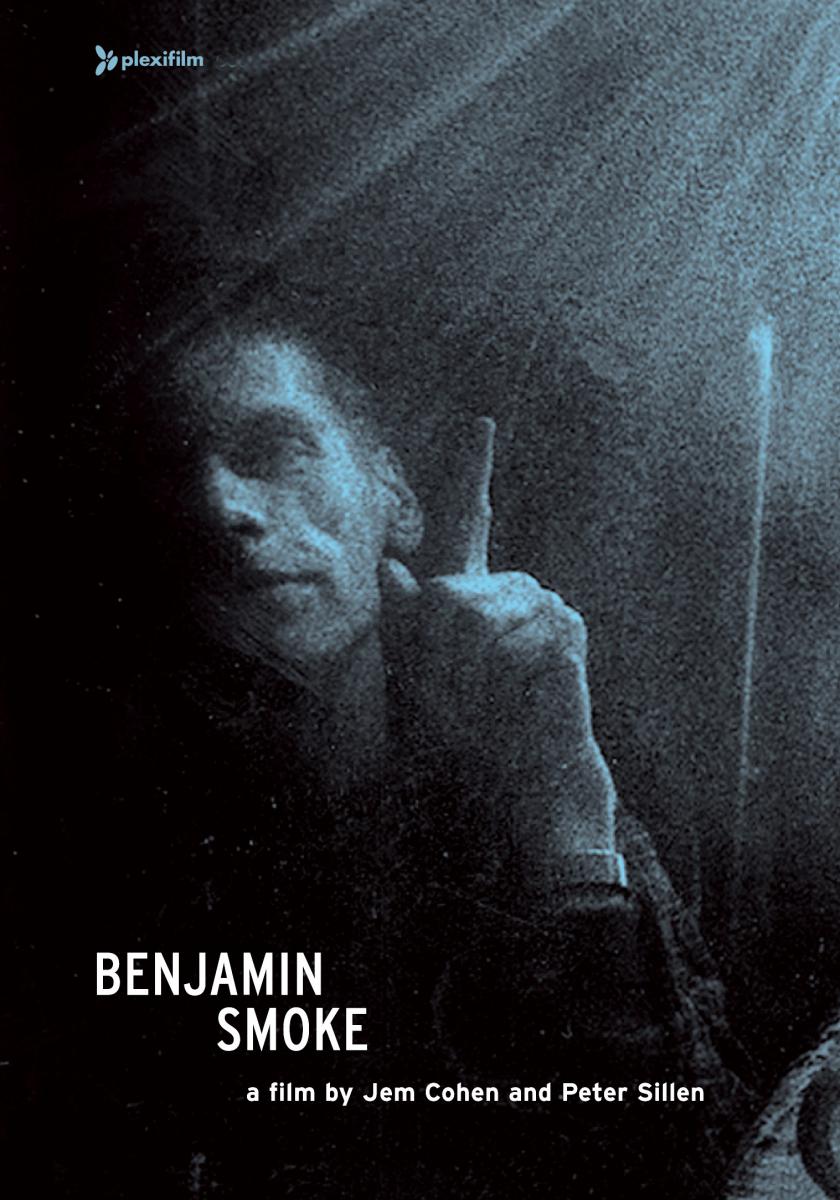

Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939) serves as an extended metaphor for the vicissitudes of Atlanta’s history and identity throughout the eight-part series, The Making of Modern Atlanta (written and produced by Chris Moser, Dana White, and Tim Crimmins, WPBA-TV, Atlanta, 1991 and 1993). We were hard-pressed to find a documentary film that could likewise be used to illuminate so many conflicting facets of the city – unless of course, we relied on White and Crimmins’ offbeat commentary on the city as the fulcrum of our documentary unit of the course. Although we viewed clips from that series in class, we chose not to focus on it because we wanted to include a range of documentary voices, including ones that spoke to changes in the city in the years after “the history twins” documented it. Sidelining that series meant we ended up with a heterogeneous set of documentaries. Voice – and Nichols’ entwined categorization of documentary “modes” – were consequently crucial in orienting our study of a film corpus that reflects and indeed participates in producing the city’s mutable, fragmented identities. Films screened in their entirety included (in this order in the course) The Uprising of ’34 (Judith Helfand and George Stoney, ITVS, 1995); Eyes on the Prize – America’s Civil Rights Movement, 1954–1985: “The Keys to the Kingdom, 1974–1980” (Henry Hampton, Blackside/PBS, 1986); The Greate$t Show on Earth (Michael Waldman, BBC 1, 1996); Sherman’s March: A Meditation on the Possibility of Romantic Love in the South During an Era of Nuclear Weapons Proliferation (Ross McElwee, 1986); and Smoke (Jem Cohen and Peter Sillen, 2000). Readers familiar with these films will immediately note that only two – the BBC 1’s snippy critique of the ’96 Games and Cohen and Sillen’s biographical sketch of musician Benjamin Smoke – focus squarely on Atlantan events and figures. In the others, Atlanta appears among a cast of contrasting cities, inviting viewers to consider it in relation to the region and nation – a task that at times tested students’ allegiance to the course thematic.

What we wanted our students to take away from these films was not a fine-grained appreciation of what they tell us about Atlanta and its larger contexts in specific historical moments, but an awareness of how their voices enact intersubjective relationships that are rooted in and somehow expressive of the city and its surrounds.

Given this larger objective, it was key that our assortment of films illustrated the fundamental distinction that Nichols makes between the expository mode of documentary, which is typified by voice-of-God narration that provides information, explanations, and explicit arguments, and modes such as the observational and participatory, which foreground relationships between the filmmaker and persons filmed (to simplify Nichols’ six-mode system somewhat). Nichols hints at the ethical stakes of this distinction when he describes the expository mode as intent on “harvest[ing], glean[ing], or compil[ing] images from the world with relative indifference.”13 Casual film viewers will be most familiar with this mode, and it is likely to be the only mode that first-year students know. This conception of documentary filmmaking as culling inert material stands in opposition to the dynamic (though not univocally so) engagements between the filmmaker and the “world” s/he films that typify the other modes.

“Something is at risk in the encounter[s]” that animate films of these modes, Nichols avers, and close analysis promises to reveal why that matters.14 To this end, we positioned the imperious British voice-of-authority at the helm of the The Greate$t Show on Earth as the expository narrator against which we viewed the participatory elements of Uprising of ’34 and Sherman’s March, and the observational approach of Smoke. In turn, they disclosed how documentary film voices can, among other things, quietly insinuate arguments, brashly conflate individual narratives and collective memory, and – perhaps most relevant to our course – exploit film’s foundation as a time-based medium to capture the palimpsestic city.

Our assignments successfully pushed our students to approach these assigned documents not as ends unto themselves – unfoldings of empirical facts or revelations of previously hidden, “true” narratives about the city – but rather as evidence of the fraught and contingent “two sides of historicity,” in the words of Michel Rolph Trouillot: both the “sociohistorical process” and “narrative constructions about that process.”15

The course’s major assignments positioned our methods (oral history, documentary film, and built environment studies) as the primary objects of study, demonstrating our scholarly investments in examining knowledge production and challenging our students’ desire to acquire knowledge. On the whole, we found that engaging our students in the critical reflection we envisioned as primary to be an ongoing negotiation – one that required our extensive mediation in the development stages of projects. At the same time, we discovered that aspects of the projects that we initially conceived of as subsidiary resonated with students in sometimes unexpectedly productive ways.For the first project, a podcast, we provided a frame: students were to create the first episode of an imaginary podcast titled “Atlanta Is . . .”

This conceit proved effective in introducing our approach to understanding the city’s identity as defined by “its ability to morph, to reconfigure itself in response to the demands of capital.”16 The assignment was founded on a question – “What is missing?” – that would come to serve as our constant refrain in the course. To even begin to answer this question, of course, one must understand to some extent what is there and appreciate that presence as the result of processes of inclusion and exclusion. Students were asked to produce their own interviews with Atlantans (students, faculty, and staff at Georgia Tech, passersby on and around campus); consider hidden perspectives and histories glossed over by their interviewees’ characterizations; and seek out archival material from the Living Atlanta, Unspoken Past, and/or the Georgia Women’s Movement project that supplemented or challenged their own interviews. The students’ interviewees invariably characterized the city today in terms of its hospitableness to diversity and commerce (namely, technology-driven entrepreneurship), and students in turn were inclined to position this view as the triumphant “after” to the archival materials’ attestation to a profoundly inequitable “before” defined solely by racism, homophobia, and sexism. In retrospect, the past/present structure of this assignment to some extent invited the simplistic progress narratives that we found ourselves struggling to help our students complicate.

Would a present-present structure have resolved this issue? Would our students have produced more nuanced or ambivalent narratives that accommodated conflicting characterizations of the city had we asked them to place their interviews in dialogue with contemporary accounts collected in, for example, Stadiumville or the Peoplestown Project? Likely so. The tradeoff there, of course, would be that students would not encounter powerful testimonies such as the reflections of black Atlantans chronicling the city’s dramatic economic and political transformations during the World War I and World War II periods, as they did with the Living Atlanta archive.

Whereas the podcast project enlisted students in recording and selecting voices that they then positioned as “representative” of the city’s image, our second project, a documentary film analysis of Sherman’s March or Smoke, asked them to consider how a particular documentary voice can be understood to “represent” or speak for otherwise unheard narratives about the city and/or region. One of the chief values of studying Sherman’s March and Smoke together lies in the marked contrasts between their protagonists and narratives. Both films center on white men of similar ages seeking artistic fulfillment and interpersonal connections – goals that often conflict with one another.

The similarities end there. The circular narrative of Sherman’s March loosely follows the route of General Sherman’s march to the sea as protagonist and filmmaker Ross McElwee self-reflectively documents his attempts to date women who stand in more and less proximity to stereotypes of Southern womanhood. This peripatetic structure highlights his mobility and the ease with which he is able to embed and detach himself from communities (and particularly women) more fixed in place by familial ties and tradition; in this light, the film makes apparent the many privileges McElwee enjoys thanks to his gender, race, and social class, yet also reveals him as an eccentric representative of patriarchy who seeks, albeit clumsily, to destabilize his position of status. Benjamin Smoke, in contrast, was pieced together from footage shot over a period of ten years at a handful of Cabbagetown and Poncey-Highland locations (e.g. Benjamin’s homes, the Krog Street tunnel, the Majestic Diner, and the Clermont Lounge) that are at most three miles apart from one another.

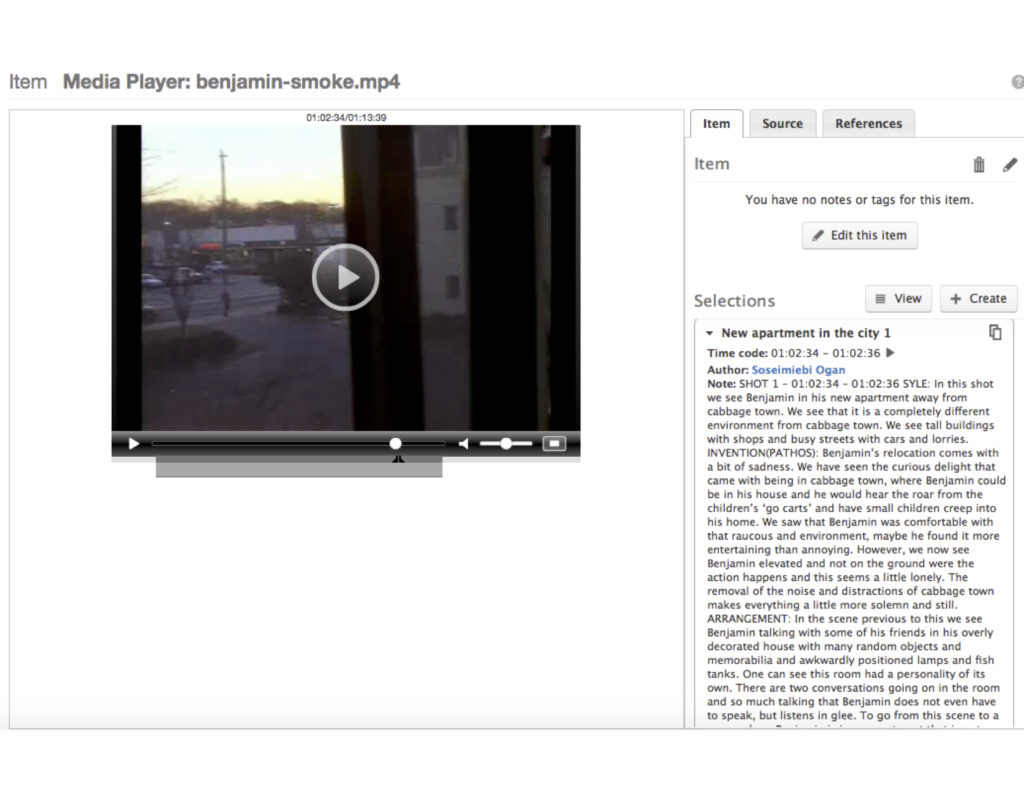

The combined expansive duration and restricted geography of the film’s production is such that Benjamin’s on-screen commentary about his experiences as a queer musician living with HIV/AIDS in the South unfolds over images of a city (and particularly the neighborhood of Cabbagetown) in flux, underscoring Benjamin’s simultaneous rootedness and isolation in the tight-knit community eroding in the tides of gentrification. Using the digital annotation software Mediathread, students created shot-by-shot analyses of two scenes that honed in on specific rhetorical features of their chosen film’s voice, and then crafted essays that examined how the film challenges and/or adds to dominant historical narratives about Atlanta and/or the South. This project brought to the fore the challenges inherent in teaching the margins as an approach to teaching the city, as students tended to view the films as asserting their protagonists’ as-yet-unacknowledged centrality in social discourse – so, for example, many initially saw Smoke as bestowing overdue recognition on a now “famous” Atlantan musician.

We took this (mis)translation of our methods to be an understandable and ultimately productive step in developing attention to the margins/marginalized and their relationship to dominant groups and forms of knowledge.The course’s final project asked students to interrogate existing historical narratives as materialized in the city’s landscape and creatively reinterpret them by proposing and creating an artistic rendering of a monument to be created on campus. In the project’s first stage, local artist and public art advocate Gregor Turk spoke with our students about Atlanta’s memorial and monument landscape; in its second stage, students explored, via a walking tour, Centennial Park, the MLK Historic District, and the historical corridor extending between them. Their reflections testified to the power of moving from Centennial Park – whose famed fountains were being meticulously cleaned when we visited – to what they registered as the surprising dreariness of the litter-laden environs of the King Center, the anchor of the MLK Historic Site. Understanding the present state of the King Center as a reflection of competing interests, financial and political negotiations, and the redevelopment of surrounding neighborhoods, students also grappled with the way that the monument stands more for, in the words of geographers Derek Alderman and Owen Dwyer, “a constant process of becoming, as present social needs and ideological interests change” than the transcendent “static” legacy of Atlanta’s most revered native son.17

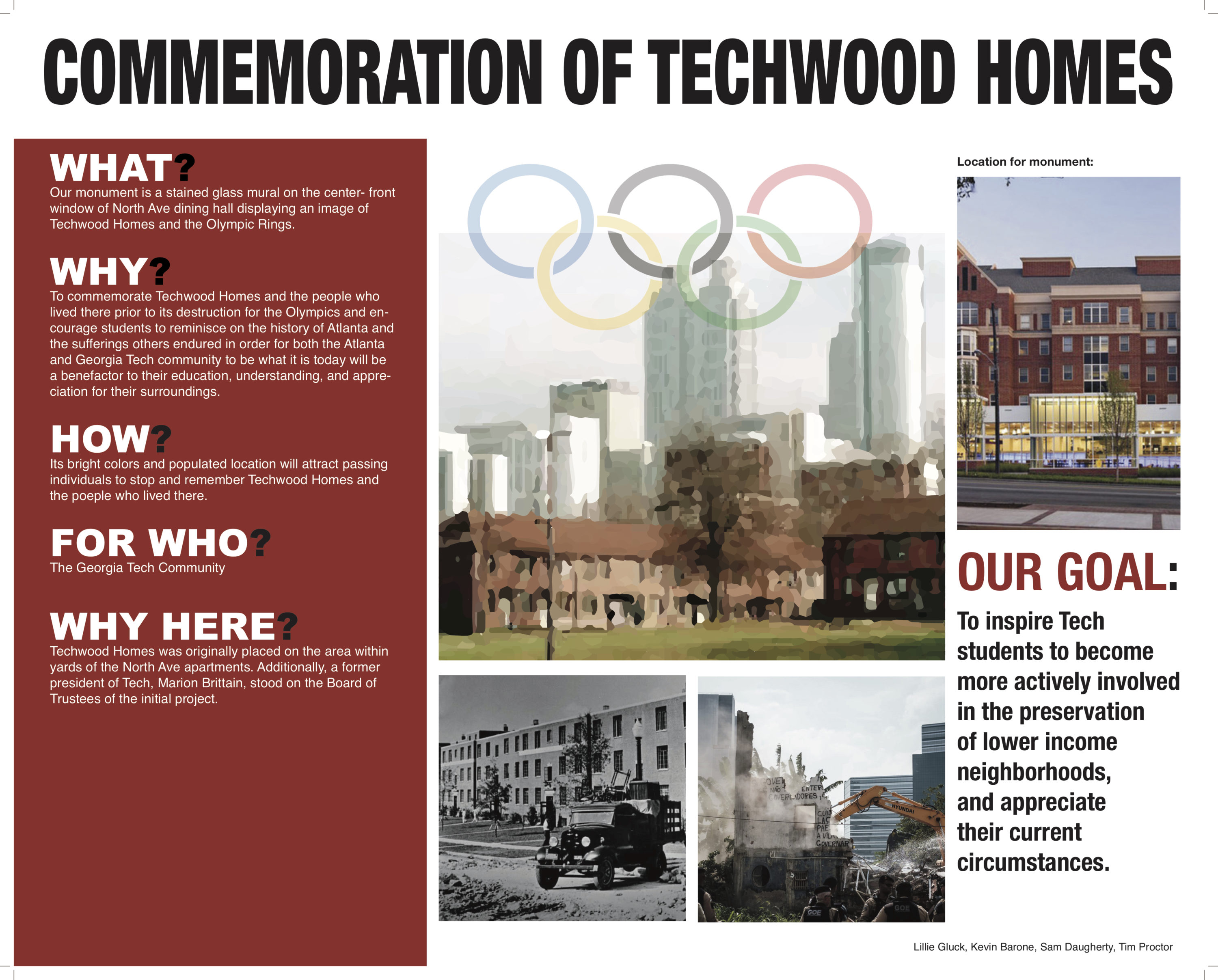

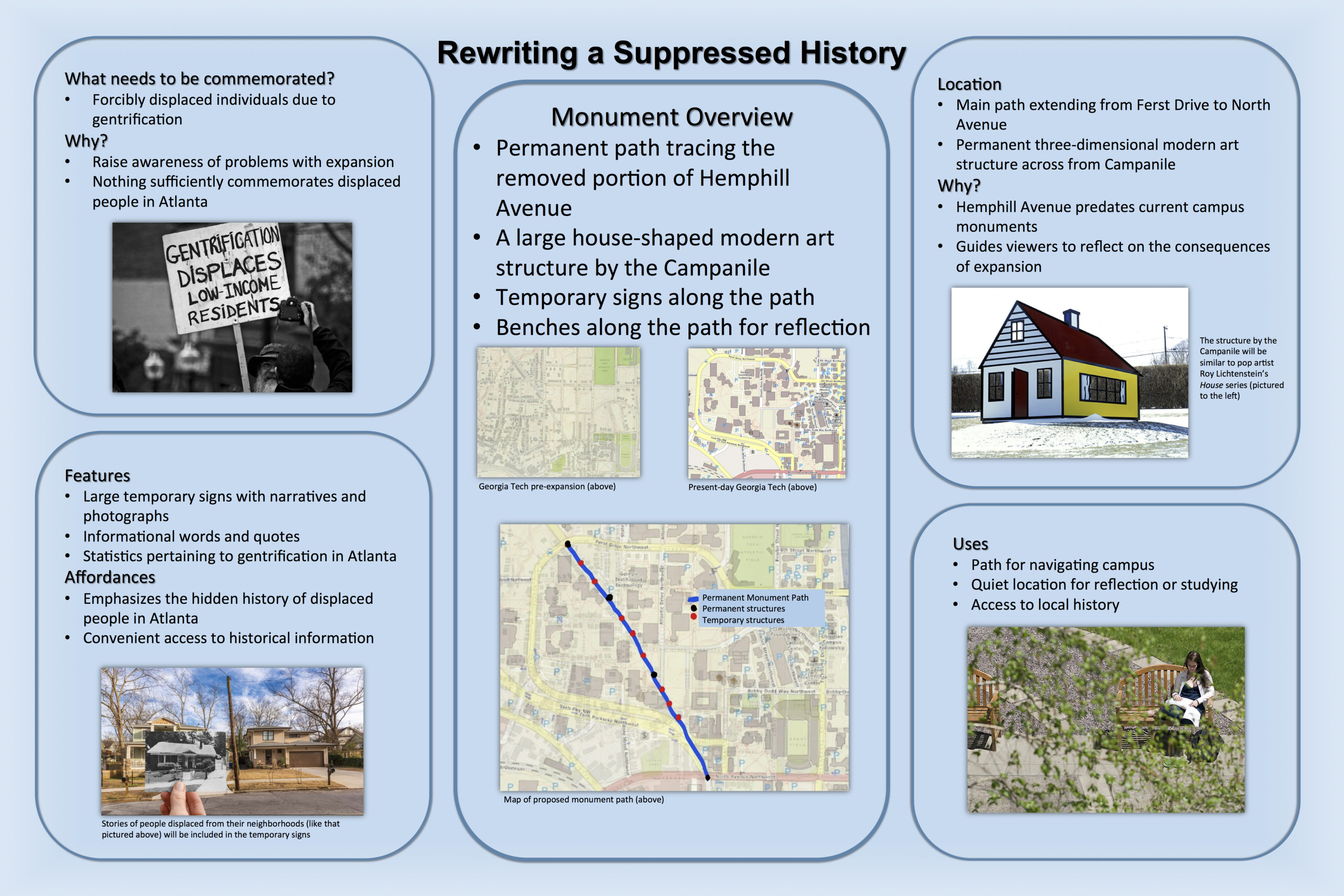

Finally, as pictured below, the students identified a silence in the city’s memorial landscape – such as the displacement of low-income Atlantans to develop downtown properties for the Olympic Games – and proposed a monument that could (begin to) address that absence, or which repurposed key mythology and symbols that we had examined (such as railroads and the phoenix) in order to illustrate their understanding of how, “memorials narrate history in selective and controlled ways – hiding as much as they reveal.”18 In this spirit of investigating what existing monuments “select” and “hide,” one student group designed a monument to the convict and slave labor responsible for the post-war railroad-building boom. Their proposed statue aesthetically quotes George Beasley’s Five Points Monument – echoing its materials, bending its railroad tracks into a crescent that cradles the figure of a laborer lorded over by a “member of the white elite.” At its most fundamental register, this project pointed students to a range of voices and representations, which they could interpret and work on in situ.

Of the primary questions that animated the early stages of course-crafting, we pursued one with particular energy: how is knowledge about cities produced, and why does that matter? Certain voices, we agreed, exert particular power in “documenting” Atlanta – forming narratives, forging representations, and configuring the city and its history in the public imagination. In both oral history and documentary film, the concept of voice – particularly “giving voice” – operates at both metaphorical and practical registers and produces rich questions for both students new to the methods and seasoned researchers. Oral history, and its kindred method, ethnography, illuminate not merely what happened or happens in a community, but the sense that people make of events through the stories they tell about them.Oral histories empower the dispossessed by “giving voice” to their interpretations of past events – or so went the thinking among academics as the method gained steam in the late 1960s. But by the 1980s, in the flurry of scholarly soul-searching and research-method revamping that the popularity of postmodern theory produced, oral historians – along with many other academics in the humanities – grew skeptical of the capacity of a method employed by a researcher (a position of relative power) to represent or give voice to the silenced or structurally marginalized. Gluck reflects that during that time, “the focus shifted [from privileging objectivity] to subjectivity, to how memory was constructed, to the implications of our narrators’ and our various and shifting positionalities [and] to an appreciation of the interview as a linguistic and performative event.”19 The “reflexive turn” in oral history undermined what Gluck calls the “naive faith in [oral history’s] empowering potential” but didn’t diminish what Bret Eynon deemed “the promise of oral history [to] go further . . . to transform the relationship between historian and audience,” and its impact in reinforcing the “democratic notions that everyone can be a historian; that memory is in itself a meaningful form of historical interpretation; and that, through oral history projects, students and others can make a meaningful contribution to our understanding of the past.”20 It is that “promise” – of transforming the production of knowledge about the past – that we were most interested in investigating with our students.While as teachers and scholars we can’t discard the framework provided by, for example, Atlanta’s success in attracting and retaining major corporations, oral history illuminates how certain stories, values, and representations, become dominant discursively.21 The impact of producing and making accessible testimony “from the margins” is political and material in nature; as historian Glenn Eskew suggests in his work on civil rights commemoration in the South, “memorialization has become a way to turn a stigmatized past into a commercial asset.”22 Oral history, then, is both essential to revealing suppressed stories and complicit in enshrining progress narratives that can seem to preclude a present marked by continuing injustice and structural violence. An interview with Alice Adams recorded in 1978 illustrates the dilemma of translating oral history methods into pedagogy. Adams’s poignant testimony includes the following reflection on her decades as a domestic worker in segregated Atlanta:

You cooking and serving their food, handling their food, but yet you can’t sit by them! You go in their house and clean their house and they say how beautifully it was cleaned, you’re an ‘A # 1 domestic housekeeper,’ but yet you couldn’t sit by them! You had to stand. Sometimes we would have little spats on the bus or streetcar – some people would just get determined – I’m not gonna work all day and stand! Sometimes we would have little flare ups, but not too much, because we knew what we were supposed to do and we did that. But we didn’t have too much trouble desegregating the buses. Not as much as they did in other places. Atlanta was one of the easiest places to desegregate the riding, any other city I’ve read . . . but before they started desegregating it we had to stand.

While offering a compelling portrait of the paradoxical intimacy and Jim Crow-enforced distance between white citizens and their black “help,” Adams also re-enshrines Atlanta as exceptional and more progressive than other Southern cities. Students drew on her narrative to support an interpretation of contemporary Atlanta as a racially harmonious land of opportunity – embodying Mayor Williams Hartsfield’s 1959 characterization of it as “the city too busy to hate” – all the more laudable for having overcome its segregated, violent past. This complicity of oral history renders it both a thornier and richer site for classroom exploration and scholarly research; in Atlanta’s case, oral history helps drive the commemoration “industry” and enriches many excellent urban histories. The evolution of a widely known and broadly respected project like Living Atlanta – which began as reel-to-reel-recorded interviews for short segments on WRFG and is now a digitized archive of more than 240 full interviews – mirrors technological developments that have given oral history methods and digital history projects even broader audiences, but also increased the ease which with they can be deployed to support a too-simple then-now dichotomy.

Teaching place – particularly a place like Atlanta – means modeling and encouraging ways of knowing that aren’t codified in a scholarly method, ways that attend carefully to a chaotic record, to a cacophony of voices that enliven the past and engulf the present. Our students were most compelled by the course’s ongoing interrogation of “how knowledge about a city is produced” when they were immersed in that din – talking to vendors in the Sweet Auburn Curb Market, listening in on exclamations of visitors descending the steps of Ebenezer Baptist Church, or noting the handful of park denizens, itinerant men and women, who, when out of eyeshot of the police, dare to make the park truly public by resting their sacks on a bench and stealing a nap. The students adopted methods as ways of asking, rather than answering questions. This mode of inquiry, in which one moves through the city looking for the most engaging absences, listening for the most elusive voices – this way of “documenting Atlanta” – proved rewarding indeed.

Cover Image Attribution: Downtown Atlanta skyline at night, looking southwest, Atlanta, Georgia, February 2, 1977. Photo by J.C. Lee. AJCNS1977-02-02a, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library. Copyright Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Courtesy of Georgia State University.

Ruth Yow is the Service Learning and Partnerships Specialist at Georgia Tech’s Center for Serve-Learn-Sustain. From 2015–2017, she was a Marion L. Brittain Fellow at Georgia Tech. She is the author of the recently published monograph Students of the Dream: Resegregation in a Southern City (Harvard University Press, 2017).

Sarah O’Brien is an Assistant Professor in the Academic and Professional Writing Program at the University of Virginia. From 2014–2017, she was a Marion L. Brittain Postdoctoral Fellow at Georgia Tech. Her current book project, Slaughter Cinema, examines documentary images of animal death in cinematic theory and history. Related writing in this vein has appeared in Screen (58, no. 4), Framework: Journal of Film and Media (57, no. 1), Cinema Journal (54, no. 3), and the volume Animal Life and Moving Image (BFI/Palgrave, 2016).