Citation: Newman, Adam P.. “From Sacred Cow to Crooked Ass Jackson – An Interview with Maurice Hobson.” Atlanta Studies. February 23, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20170223

During the dialogue, Hobson – assistant professor of African American studies at Georgia State University – drew on his deep knowledge of Atlanta as author of the book The Legend of the Black Mecca: Politics and Class in the Making of Modern Atlanta, forthcoming from the University of North Carolina Press. In this blog post, Hobson speaks with Atlanta Studies about his research and relationship to the city.

You write about Atlanta in The Legend of the Black Mecca: Politics and Class in the Making of Modern Atlanta and are currently living and teaching in the city, yet you are not originally from Atlanta. What is the history of your personal and academic relationship to the city? How long have you been writing and thinking about Atlanta?

The truth of the matter is I’ve been working on research about Atlanta since my senior thesis in 1998, when I was in college at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. So we’re talking two decades worth of thinking about the city. And I still remember riding around Selma, Alabama, with one of my best friends listening to Outkast and Goodie Mob’s music on a boom box because the car had an eight-track player, and how that experience pushed me in a new direction. In a way, my current research all started in that car.

Can you tell us about your personal relationship to Atlanta?

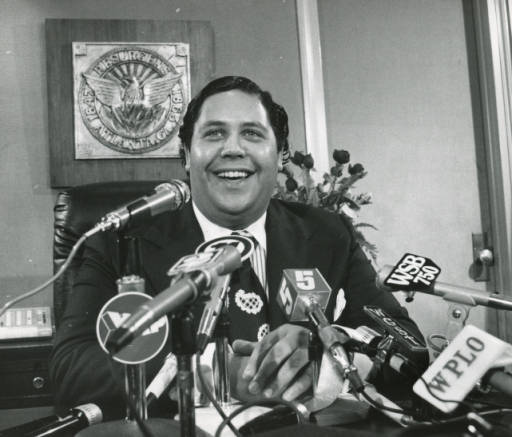

It all started when I was five years old or so. I was at a Red Lobster here in Atlanta and this really large black man walked into the room with a really loud voice and my parents were like “Oh my God, it’s Maynard Jackson!” He walked around the room and he shook everybody’s hand and he kissed babies and all that kind of stuff and it was almost like Jesus Christ had walked into the restaurant.

In the spring/summer of 1994, when I was seventeen, Outkast, this rap group from Atlanta, dropped this hip hop album southernplayalisticadillacmuzik. My older brother had gone to school at Howard University and when I would go visit him he would take me to parties and you would have to go to either the East Coast parties or the West Coast parties. You would have to choose up, right? And this is the height of The Chronic coming out, Tupac is on the rise. You’ve got all this stuff going on. Well, when Outkast drops this album southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, I mean, they’re suddenly speaking in a southern vernacular, you know, “ain’t no thing but a chicken wing.”

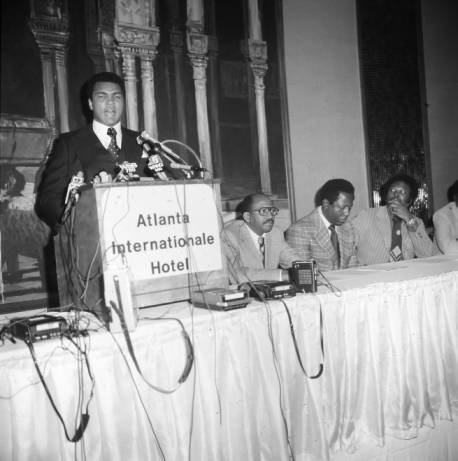

They’re talking about things I actually understood because Selma’s proximity to Atlanta meant we were coming to Atlanta to get cool sneakers or to go to Six Flags so I kinda knew the landscape. And I just had this kind of love for Atlanta because it was just so different from growing up in rural Alabama. I mean, it was the city.Then, in the summer of 1996, as a sophomore in college, I worked for Coca-Cola during the Olympics. If you’ve ever been to a convenience store and you’ve seen these barrels of ice with soft drinks in them – well my job was to make sure the drinks got into the barrels of ice. But I had the opportunity with my own two eyes to see Muhammad Ali light the torch and to see Michael Johnson break all those records. And what was crazy about it was that because I’m a southern boy – I had grown up just next door in Alabama – I was amazed at how it seemed the whole world was actually here. I fell in love with the idea of the Olympics.

And can you tell us a bit more about how you came to write this particular book about Atlanta?

Well, in 2001 I wrote a master’s thesis entitled “What Y’all Really Know about the Dirty South?: Working Towards a Black Southern Aesthetic in Hip Hop Culture” that focused on Outkast and Goodie Mob and some of the others and how southern hip hop was more conscious because it remembered the injustices black people had faced. From there I ended up going up to the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.

And now going back to that first experience I mentioned, meeting Maynard Jackson in Red Lobster when I was a kid, what struck me later was that Cameron Gipp from Goodie Mob calls him “crooked-ass Jackson” on an Outkast song, “Git Up, Git Out.” Ultimately, the bulk of my research comes from the dissonance between how my parent’s generation saw Maynard Jackson — as a sacred cow, and he was a unique, very powerful, very loving politician — and how my generation called him crooked-ass Jackson. The conversation is how did the popular political sentiment go from that in one generation to this in another. That’s what I try to explore in this book.But this is the thing. I was going to Illinois to write a dissertation on private historically black colleges and the black power movement. I had decided to move away from the hip hop stuff because it felt a little too sexy. I wanted something with some girth that I could have different kinds of conversations with. And then I took a course with David Roediger and Adrian Burgos Jr. that was called “Race and the City” and we were looking at policies that created real issues in urban environments. A lot of that course focused on cities like Chicago, New York, and San Francisco and we didn’t really discuss the South. But Outkast and the Goodie Mob started talking back to me. So in that class I created this new paradigm that I called the “Black New South” which looks at how the policies that came out of the Civil Rights Movement, specifically the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, politically changed the American South in major ways. When that legislation was passed, it signaled to the black world that maybe the South had become the last frontier and I thought Atlanta was the best city to study what came out of that. So I married all of my interests together and I wrote my dissertation, “The Dawning of the Black New South: A Geo-Political, Social, and Cultural History of Black Atlanta, Georgia, 1966–1996.”

How has the experience of now teaching, writing, and living in Atlanta shaped your thinking as you’ve continued to develop this work?

Perhaps the best example of this comes from a conversation I had a couple of months ago with my editor at the University of North Carolina Press where the book will be published. He had told me that some higher ups at the press wanted to change the title of the book to “No Black Mecca” or “The Myth of the Black Mecca.” He knew I wouldn’t like this, and when we spoke I told my editor he had to explain my position to those higher ups as follows: I recognize my station here, I love Atlanta, I am a card-carrying member of the black middle class, I am stamped and approved, and there are a lot of people in this community who have given me a lot of information, and if I allow for the book to be called “No Black Mecca” or “The Myth of the Black Mecca” then I won’t be able to live and prosper in Atlanta, because as I lay it out in the book, this is a unique place for black people and it does represent the highest aspirations and achievements of black America over the last one hundred years. Now there is also this other side, this underbelly, that has never been engaged and which bears witness to some of the most destitute conditions for black folk at the very same time. And my new book aims to showcase these tensions. So, I felt that calling it the “Legend of the Black Mecca” meant that there is truth to the idea, because with a legend it may have been embellished over a period, but there is still truth. But if I were to say myth instead, that means it’s all a lie and I told him I just don’t feel comfortable with that because I need to be able to live in Atlanta.

Are there stories related to Atlanta that didn’t make the book but which you still hope to write about?

One of the things I don’t talk about in the book but which I have been thinking about how to frame in relation to its narrative is the Muhammad Ali vs. Jerry Quarry fight in 1970 and how Ali is central to the presentation of Atlanta as this Black Mecca. Part of the reason I don’t get into that in the book is because in it I try to really focus on Atlantans on the ground. But I see that as another project that could supplement my explorations of the city in the book.

On that note, what directions do you see your research going in next? Will you remain focused on Atlanta?

Atlanta is rife with history, particularly African American history, so there are many things I could do just with the city. But I do feel I have a higher calling, in terms of further cultivating this paradigm that I call “The Black New South.” I mean you can do comparative studies of Charlotte and Atlanta, or Jackson and Atlanta, or Birmingham and Atlanta, because the Black New South manifests differently in these different places with different histories. And some of my thinking on this also speaks to the larger Global South. For instance, the case of Olympic cities in the Global South and how they were franchised for world consumption. One example I would be interested in studying is Rio De Janeiro, which had very similar issues to Atlanta and Atlanta’s Olympics. I’m also interested in doing a comparative study of Black Mecca conversations with Salvador de Bahia, in Brazil, and Atlanta. There are a lot of possible directions, but I could also just go on and on with Atlanta.

Karen Beck Pooley is a Professor of Practice of Political Science and co-directs the Small Cities Lab at Lehigh University. She also serves as the Director of Research and Analytics at czb LLC, an urban planning and neighborhood revitalization consulting firm. She previously ran Allentown’s Redevelopment Authority and was a Deputy Director within New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. She has a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from Wellesley College, a Master of Urban Planning & Policy from New School University’s Milano Graduate School, and a Ph.D. in City Planning from the University of Pennsylvania.